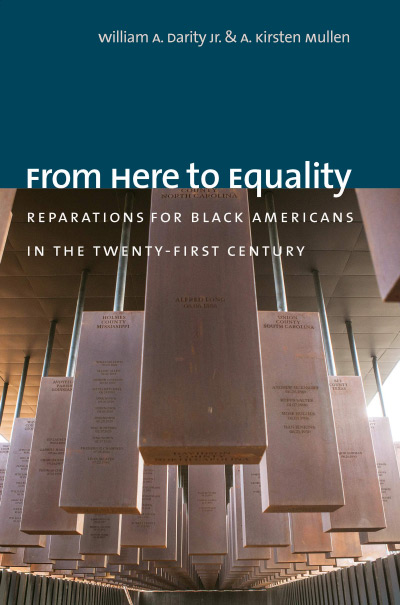

The principal author, William A. Darity, Jr., has had a distinguished academic career. His research record is excellent, as reflected by his Google Scholar statistics and numerous awards and appointments. He was more or less born into academe. He spent part of his youth in Amherst, Massachusetts. His father was a trustee at the University of North Carlina. He was educated at Brown University, the London School of Economics and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. If Congress adopted his recommendations, he would qualify for reparations.

First, the good news. The authors have written a book that provides several seemingly good arguments for reparations that can be used by those who have a predisposed notion that paying reparations for slavery is a good idea. They can be used as ammunition in friendly debates. The book is scholarly. The notes start on page 289 and do not stop until page 393, more than a hundred pages later. The authors have obviously done their research.

Now for the bad news. Their entire argument is based on a non sequitur, which might be stated as follows: Blacks have been oppressed in this country for centuries, therefore the present generation should be forced to pay reparations to those blacks who are still alive. It is a basic principle of justice that one person shall not be held accountable for the crimes of another person. The reparations argument violates that basic principle of justice. But let’s get into the specifics of their arguments.

Darity and Mullin make some seemingly good points in the Introduction. There are precedents for reparations—for victims of the Japanese-American internment during World War II, and for survivors of the Holocaust, for example. Does it follow that Americans of African ancestry should therefore qualify for reparations as well? They would like us to believe so. However, there are some major differences between the Japanese and Holocaust reparations and the reparations the authors propose, some of which have been outlined by Rhoda E. Howard-Hassmann (2004, “Getting to Reparations: Japanese-Americans and African Americans,” Social Forces 83 (2) [December]:823 – 840). Perhaps the main difference is the fact that in the cases of the Japanese and Holocaust reparations, the actual victims were compensated, whereas in the case of black reparations, individuals who are four or five or more generations removed from slavery would be the group compensated.

But the argument is more complicated than that. The progeny of those slaves have suffered from discrimination, partly because of the Jim Crow laws, which were passed by legislators who have been dead for two or three generations, and by private individuals, some of whom are still alive. Some of the Americans of African descent who have suffered because of the remnant of those Jim Crow laws are still alive as well.

Much of the book builds the historical background that will later be used to justify paying reparations. Chapter 1 provides a political history of America’s black reparations movement. There are some comparisons to that of the Russian serfs who, when freed, actually received something (land and farm implements) with which to start their new lives as free men, whereas the freed slaves received nothing but their freedom in many cases. Chapter 2 discusses the myths of racial equality. While some polls show that many people, both black and white, believe that racial inequality and discrimination no longer exist, such is not the case. Discrimination and inequality continue to exist. Blacks and whites have differing opinions about the extent to which current discrimination inhibits blacks from getting ahead.

The fruits of slavery were reaped not only by slave owners, but also by northern industrialists and those who conducted trade with the West Indies. One need not own slaves to benefit from slavery. The economic expansion that took place in the United States prior to the Civil War was partly the result of slave labor (although historians dispute the importance of slavery in this expansion).

There are some historical errors in the book. For example, the authors state that Thomas Jefferson was 37 when he wrote the Declaration of Independence, when in fact he was 33 (p. 76), a minor point that can be ignored. A point that cannot be ignored is the authors’ claim that “The American revolution was fought, in large part, by a colonial elite to preserve their right to human property” (p. 78). One might challenge the view that the war was fought by a colonial elite, since it was fought mostly by common men, although it is true that some of the leaders of the American revolution were members of the upper class. The fact that some members of the elite wanted to preserve slavery cannot be disputed, but the authors seemingly take the position that preserving slavery was the primary motivation for the war when in fact it was not.

The authors discuss some alternatives that, if implemented, would have led to the freedom of the slaves, and would have avoided war. One idea that was suggested at the time was to have the federal government purchase the slaves’ freedom from their owners, but that idea was never implemented. Slaves who managed to escape by fleeing to the north were not exactly greeted with open arms. Some states passed laws prohibiting them from settling within their state’s boundaries.

Although justifications for reparations are discussed throughout the book, the argument heats up in the last two chapters. In chapter 12, they address some of the arguments that have been put forth against the case for reparations, then attempt to dismantle those arguments.

“It was so long ago; there is no reason to keep bringing up slavery” (p. 240). The authors counter by pointing out that some blacks who are still alive knew somebody who knew somebody who was a slave, which is a way of pointing out that slavery is not that many generations removed. It’s an argument I can relate to. My great grandfather was still alive when I was born. His father fought for the North during the Civil War and did not die until 1929. But the authors don’t stop there. They argue that having ancestors who were slaves is not the only justification for reparations; another justification is the post-Civil War hardships they and their progeny had to endure because of discrimination. They provide some examples to bolster their argument.

The problem with their rebuttal of this argument is that many millions of the individuals who would be called upon to pay these reparations never discriminated against blacks, either living or dead. It might also be pointed out that it is inherently unjust to force some people to pay for injustices that were perpetrated by others.

“Wouldn’t black reparations only create more animosity between the races?” (p. 243). Their counterargument is that “The majority of the populace. . .must accept national responsibility for the damages inflicted on black people” (p. 244). That’s not much of a rebuttal. It’s philosophically untenable. There is no such thing as “national” responsibility. All responsibility by its very nature is individual. Forcing non-blacks to pay reparations to blacks is certain to create more animosity between the races.

“Demands for reparations should be directed at the African countries, since some Africans sold other Africans into slavery” (p. 244). Their rebuttal is that “the United States is where ancestors of most of today’s black Americans were forced into slavery” (p. 244). While that statement may be true, it’s not much of a rebuttal. It is inherently unfair to force some people to pay for harms that were caused by other people. It doesn’t matter whether people in African countries are being forced to pay or whether it is Americans who are forced to pay.

“Groups who bear no responsibility for slavery will be compelled to foot the bill, particularly groups who immigrated to the United States long after slavery was over” (p. 245). Their rebuttal is that those immigrants came here voluntarily, and that they are benefitting from the high standard of living that was made possible by the slave labor of generations past. Also, the whites and Asians who came to the United States from the 1880s to the present have benefitted from the Jim Crow laws that established a racial hierarchy, which they still enjoy. The third, and to them the most important part of their rebuttal, is that “black reparations is a debt that must be borne by all Americans” (p. 245). They also state that the reparations should be paid by the federal government rather than individuals. The weakness in this argument is that the federal government has no assets of its own. Whatever assets it has, it must first take from someone, and since many blacks pay taxes, some of the funding for reparations would have to be paid by blacks.

“Didn’t white America (or America in general) already pay its debt for slavery in blood by waging the Civil War, which resulted in emancipation?” (p. 245). The authors attempt to rebut this argument by arguing that the harm caused by slavery requires compensation, and that merely emancipating the slaves was not enough. Again, the argument fails, for the same reasons stated above. It is inherently unjust to force some people to pay for the injustices perpetrated by other people.

As an aside, I might mention my great great-grandfather again. He volunteered to join the Union army in April 1861, and was mustered out in June 1865. He was injured in three Civil War battles. If he is like most Union volunteers, he enlisted to preserve the Union, not to free the slaves. He gave up four years and two months of his life to preserve the Union, and one result of his sacrifice was that the slaves were emancipated. Should I be entitled to compensation for the sacrifices he made? Should this generation of blacks be forced to pay me something because one of my ancestors is partly responsible for their freedom? Does this sound like a ridiculous argument? Is it any more ridiculous than the argument that the present generation should be forced to pay for injustices perpetrated by others more than 150 years ago?

“Blacks already have received reparations in the form of an abundance of welfare monies and funds from other social programs” (p. 246). The authors point out that blacks were not able to reap the full benefits of the welfare system until 1965, and that those welfare programs were open to all races, not just blacks. In some cases, certain welfare programs were targeted more to whites than to blacks, who were sometimes left out of some of those programs. That’s not much of a rebuttal, just like the original argument is not much of an argument.

“Blacks already have received reparations from affirmative action programs” (p. 248). The authors point out that affirmative action programs have served as antidiscrimination programs, not an attempt at reparations. Those programs have served to desegregate elites. The authors make a good point. Stating that affirmative action programs are a form of reparations is a weak argument, just like saying that the current generation has a moral obligation to pay for past injustices that were perpetrated by others who are now long dead.

“Why should blacks receive reparations when other groups have strong claims and are not asking for much?” (p. 250). The authors do not attempt to refute this argument. Instead, they suggest that other oppressed groups, especially American Indians, might also have a just claim for reparations.

“Reparations paid to Japanese Americans and Holocaust victims were made to direct victims and/or their immediate families; therefore, these are not precedents for black reparations for slavery” (p. 250). Their response to this argument is that delay in paying should not absolve the community of the obligation to pay, since injustice has intergenerational effects. The weakness in this rebuttal is that communities, per se, do not exist. They do not eat, sleep, breathe or think. Only individuals do these things. Communities do not pay. Only individuals can pay.

“Reparations demean the memory of the victims who cannot speak for themselves” (p. 251). The authors point out that they, as well as others who still live, have been the direct victims of Jim Crow, and can still speak for themselves. But the real issue here is whether it would be just to force some people to pay compensation to others when those who pay are not guilty of any injustice. They do not address this issue.

“Dwelling on slavery and pursuing reparations perpetrates a crippling psychology of victimization among blacks” (p. 252). The authors respond to this argument by stating that it is racism that cripples black Americans, not an alleged victimization mentality. Well, they are entitled to their opinion, but numerous scholars would agree that reparations bolster the victimization mentality.

“When all is said and done, today’s blacks are better off having had their ancestors enslaved here. Very few of them would opt to return to Africa rather than stay in the United States” (p. 252). The authors dismiss this argument, merely stating that black Americans’ ancestors did not come here by choice.

“Black reparations, unfairly, will ignore the parallel plight of the white poor” (p. 253). The authors argue that the black injustices caused by slavery present a different case. Black poverty and white poverty are not the same.

“Regardless, there is no way to pay enough to compensate for the evil of slavery” (p. 254). The authors agree that it would be impossible to fully compensate for the evils of slavery, but they argue that significant compensation could be made even though it would never be sufficient to compensate for the injustices of slavery. While it is true that practically any amount of reparations paid to the actual slaves would be insufficient, nobody is talking about making payment to the slaves themselves. The weakness in their challenge to this argument is that the people receiving the reparation payments (those living today) were not the ones who suffered the injustices.

In the final chapter, the authors present a detailed program of reparations for black Americans. Basically, the payments would be made by the federal government. They believe there is a collective national obligation to pay; that the federal government is responsible for sanctioning, maintaining, and enabling slavery; and the segregation and continued racial inequality that resulted therefrom. The bill should go directly to Congress.

In order to qualify for reparations, U.S. citizens would need to prove that they had at least one ancestor who was a slave after the formation of the republic, and they would have to prove that they self-identified as black at least twelve years before the enactment of the reparations program or the establishment of a commission to study the issue. Then there is the question of how much the bill should be, and how the proceeds should be distributed. A number of suggestions are put forth, but they are all pointless, since reparations should not be paid in the first place, because the individuals who would be forced to pay (all taxpayers) have no moral obligation to pay.

The value of this book, and it does have value, lies not in the arguments to justify reparations, which cannot hold up to analysis, but in the detailed and meticulous documentation of the hard struggle that prior generations of blacks have faced living in the United States.