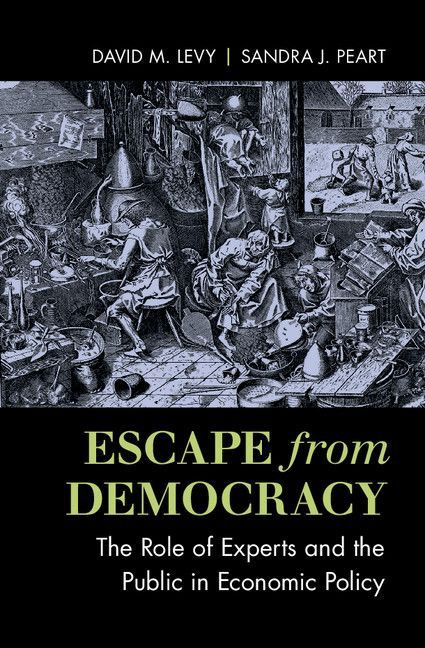

Escape from Democracy is a sociological and historical exploration of why we have allowed experts to determine so much of our decision-making in public policy, and why this change in social preference has usurped “democratic” outcomes. An overarching theme in the book is that experts are self-interested, as is the rest of society, so expert insiders can harm outsiders, most simply due to information costs. This expert harm can be unintentional.

Escape is recommended for the scholar of the history of economic thought. It is a tour de force in this field. This being said, probably most HET scholars already know of this work or its contents in other forms. So this review is intended to distill the main ideas for a more general readership. (For disclosure, I studied with the authors in their co-hosted Summer Institute (SI) for the History of Economic Thought held at George Mason University and then the University of Richmond, where they workshopped much of the research contain within.) David Levy is Professor of Economics at GMU and Sandra Peart is the Dean of the Jepson School of Leadership Studies at the University of Richmond.

Levy and Peart have written or edited more than twenty articles and books together or with co-authors. As stated above, a significant result of this research is Escape from Democracy, which is in-depth scholarship in a unique and entertaining way. The work is masterful in its use of archives and images—including political cartoons, caricatures, letters, legal documents (David Levy is a photographer and told me one of the reasons they went with Cambridge is that the publisher would use quality paper for the book’s images), folk-wisdom and stories around alchemy and John Law’s “system” of the 1720s, and graphics from modern textbooks (the source of conventional wisdom)—as they tell their story of how our dependence on experts has replaced public discussion on public policy issues.

This book is part of, and a significant stock-taking representation of, the authors’ larger project on analytical egalitarianism. The “Vanity of the Philosopher” (2005) and The Street Porter and the Philosopher (2008, both Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press), an edited work from papers presented at the SI, are earlier works in this project. The project starts with Levy’s 2001 treatise How the Dismal Science Got Its Name (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press),“dismal” because many political economists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries believed that all people are capable of realizing their own chosen ends, thus slavery is not the natural order for political economy. Thomas Carlyle found political economy a “dismal science” upsetting racially-based hierarchy and thinking, which re-emerged with eugenics in economics in the Progressive Era, and which thankfully, has dissipated in mainstream economic thought today.

Public Choice Thinking

The story our authors tell is mostly from a HET perspective. We start with Frank Knight (1885-1972) from the University of Chicago, “for whom democracy is government by discussion” (emphasis in original, p. 7). Knight is the ideal-type from which the change in economic thought moves us from discussion to experts. There are two interdependent models introduced to help understand this change. “A key question in this book is whether policy goals are determined once and for all and then implemented by experts (what we call the linear model) or whether they are determined in an on-going process of review and discussion (what we call the cyclical process)” (p. 8). In the common language of politics, the second, better model, might be realized through sunset legislation in the modern American legislative context.

The linear model depends on experts being both trustworthy and effective. It neglects the temptation associated with power, with having the means to achieve an end that, once chosen, becomes disassociated from the people who apparently chose it. There is no guarantee that those who implement a policy are trustworthy or effective or that they are impervious to temptations associated with power. Nor is there any reason to believe that they will choose the means that best serve the articulated goals of the group instead of the means that best serve their private goals (p. 9).

Th[e] problem associated with the linear model is known in the economics literature as “regulatory capture.” After goals are agreed on, those who implement them may use their authority to achieve their own, private goals. Charles Wolf coined the helpful term “internalities” to describe the private goals of those entrusted with implementing public policy. . . . Regulatory capture by those with such private goals is now seen as a central explanation for government failure. A theme of this book is that, like the policy makers themselves, experts who provide advice to policy makers and who design the means of implementation may also be subject to regulatory capture (pp. 9-10).

Welfare Economics

What changes economic thinking from endogenous to exogenous policy goals is “New Welfare Economics.” “Samuelson’s 1947 Foundations was perhaps the high water mark for new welfare economics. Samuelson developed social indifference curves that depended only on transitivity” (p. 82). What this means in general terms is that people’s (economic) preferences are known and unchanging, and, therefore then, redistribution by experts can bring a greater societal good than individuals choosing for themselves. This redistribution for the greater good is also known as utilitarianism, or, the transfer-state under which we live today. The transitivity assumption is a step towards the insider “science” of economics and the rise of the (mathematical) economic expert. This paradigm co-emerges with game theory during the Cold War.

The subchapter “Experts Who Pick Results to Support the Ends” provides an illustrative case study—the work of Karl Pearson and Margaret Moul, whose research was conducted during the 1920s immigration debate. Levy and Peart show how Pearson and Moul created a method of research in order to present the findings they had already determined to show, which in this case is that Jewish people were “inferior” because of consumption patterns. Jewish children were not as well dressed as everyone else, therefore their parents were slovenly.

Some eugenicists at the time identified lower time preferences with racial superiority. Pearson and Moul would have to conclude that Jews were superior. But Pearson and Moul were silent on where the income went. Instead, they concluded that lower expenditures on clothing was evidence of a racial failing, for which intelligence might compensate. They used the result to argue that Jews should prove they are superior in intelligence to make up for their poor physical traits and habits (emphasis in the original, p. 106).

Here the finding is subtle but profound. The choosing of data, and/or choosing a research method based on data available is a valid critique of economic analysis whether or not it is part of a larger ideological project.

Samuelson’s Textbook

One of Escape from Democracy’s most interesting research avenues considers how Soviet growth is depicted in American economics textbooks, especially the canonical college textbook during the Cold War period, Paul Samuelson’s Economics (1948-1980). Samuelson showed Soviet economic growth to be, within “scientific” possible ranges, about twice that of the U.S. during the period 1961 to 1970, with dates at which Soviet real GDP would overtake that of the U.S. Yet of course, this never happened, and we find that the projected dates for this leap-frogging were pushed farther-out into the distance in subsequent editions of Economics.

Soviet growth didn’t reach these projections “because of bad weather and crops and shortening of the workweek” (Samuelson 1970, in Escape, p. 120). Our authors are too methodologically sound (and polite) to identify this skewing of data and projections as overt ideology on the part of Samuelson and in fact find a benign reasoning. “Like McConnell’s pie chart, Samuelson’s overtaking graph is always the first graph in the last chapter of the book. There are, however two editions—the seventh of 1967 and the eighth of 1970 ... in which the projection is the first graph that students see. Perhaps the projection is offered as a key motivation to study economics” (pp. 119-120).

Transparency

One of the main reasons that Escape stresses conversation over experts is that the cyclical public policy process provides more transparency than does that of the linear, expert-driven, model. An example is the National Bureau of Economic Research’s study of bond-rating agencies (The Corporate Bond Project 1941). Our authors show how the data used in the published study does not identify the specific rating agency determinations and only shows summary results, in other words, firm-specific data are concealed in the report. Levy and Peart find that the reason for this lack of transparency is so that the researchers can gain the cooperation of the rating agencies (the same rating agencies who provided the poor ratings for the mortgage-backed bonds helping to cause the housing boom and bust leading to the Great Recession) during the research and writing of the report in the 1930s.

Why would the expert conceal things? One answer that we have stressed throughout the book is sympathy for a system, for a client, or for one’s group. Of course, there may instead be material motivation but we stress sympathy because that is what we consider the glue of faction. Faction has long been viewed as the great problem of republican governance. A central text of the American founding is James Madison’s tenth essay in the Federalist Papers. The question addressed is how to break up faction without destroying liberty (p. 237).

This leads to my only criticism of Escape from Democracy. Yes, Madison warns of faction in No. 10. However, in this essay Madison also argues for the Constitution (against the views of the Antifederalists) because a larger (centralized) polity will reduce local factions by allowing voters to have a larger pool of representatives to choose from and therefore be able to better choose more enlightened persons for these offices. “The question resulting is, whether small or extensive Republics are most favorable to the election of proper guardians of the public weal: and it is clearly decided in the favor of the latter” (Federalist Papers, Alexander Hamilton, James Madison and John Jay, New York: Pocket Books, 2006, p. 66).

Madison’s “proper guardians” expresses the reverse ontology from that of public-choice, that there may be (enlightened) people who can guide the nation better than others. This appears contradictory to the “politics without romance” public choice espoused throughout the book, and is what Edgar Allen Poe parodied as “perfectibility man,” that changing circumstances will “improve” human nature. This is, of course, Marxism’s “raising of consciousness” after the proletarian dictatorship, after which the state is allowed to benevolently wither away. It is anachronistic to see this image here, of an enlightened leader via Madison, in Escape from Democracy. Governance by a perfect(ed) person, is as Michael Munger describes, governance by “unicorn.” A reference to Madison is not necessary, we have known the public choice insider-outsider method, which may be more general than faction.

Aside from the Madison mis-step, I enjoyed seeing this book come to fruition, and it is a substantial and beautifully-illustrated contribution to classical liberalism.

| Other Independent Review articles by Cameron M. Weber | |

| Fall 2023 | Realizing the Values of Art: Making Space for Cultural Civil Society |