It is hard to think of a human enterprise that has been more successful, or more consequential, than science. Beyond all the technological benefits it has made possible allowing us to enjoy longer and more comfortable lives, science has fulfilled some of humanity’s grandest theoretical longings. Thanks to science, we now have a solid understanding of the laws by which the entire universe operates, along with a pretty good idea of how it began and then evolved with the generation of stars, planets, and life.

One theoretical longing, however, remains unfulfilled. This is the desire to know the difference between right and wrong. Granted, many people think they know what morality is, a situation evidenced by the virtue signaling regularly displayed on social media. But disagreement still prevails on even the most basic moral questions, despite two and half millennia of reflective effort by Western philosophers. No knock-down argument, no decisive piece of evidence, has yet been produced to firmly establish a theory of ethics.

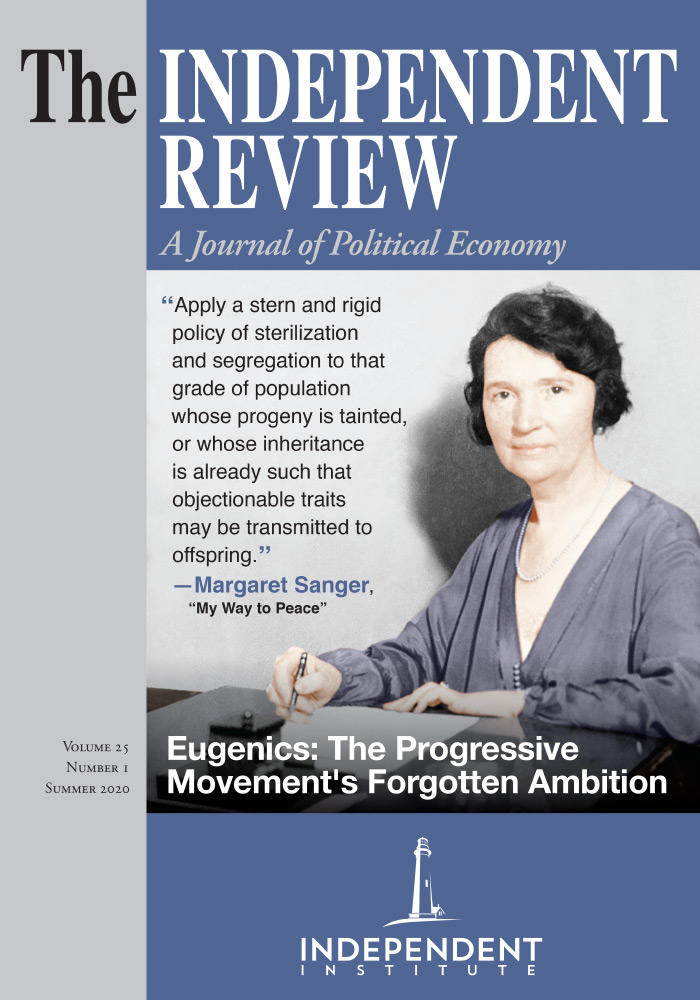

Can the methods of science that have proved fruitful elsewhere be summoned to accomplish this unresolved task? Over the past several decades, thinkers from a variety of disciplines—mainly psychology, neuroscience, and evolutionary biology—have taken up the challenge by adopting a scientific approach with a view to uncovering the touchstone of morals. The luminaries of this movement have authored best-selling books, including Steven Pinker, Jonathan Haidt, and Joshua Greene. Critically analyzing this project is James Davison Hunter and Paul Nedelisky, both scholars at the University of Virginia, in their book, Science and the Good: The Tragic Quest for the Foundations of Morality. Hunter and Nedelisky provide a solid description of that quest, but their assessment of it as tragic goes too far.

To call this science new is to suggest that there was an older version that present-day thinkers are continuing. Indeed, that is the case, as Hunter and Nedelisky recount in the opening chapters of their book. The science of morality has a long history going back to the late Renaissance period when philosophers became inspired by the achievements of Galileo and Isaac Newton to overthrow the then reigning ancient-medieval conception of ethics. The philosophers that embarked on this mission argued that the ancient-medieval tradition had failed to generate a consensus on ethical principles. This failure proved catastrophic once the Roman Catholic church lost its monopoly on religious dogma in the West as a consequence of the Reformation. Europe subsequently descended into a protracted series of wars over contested visions of the moral universe. To scientifically minded philosophers of the time, the fundamental flaw of the ancient-medieval outlook was similar to what previously held back progress in the physical sciences—namely, the belief in a natural telos, the idea that all things have a purpose which philosophers are supposed to discover if they are to obtain a complete account of reality. With respect to human beings, the ancient-medieval synthesis maintained that our purpose was to actualize our highest rational capacities in this life and arrive at union with God in the next. As Hunter and Nidelisky rightly observe, the early proponents of the science of morality held that a judgement on the purpose of our existence was mired in controversy.

It was because they wanted a less disputatious basis for morality that these philosophers appealed to science. Some invoked the mathematical underpinnings of science, with Hugo Grotius, for example, constructing a theory of natural law from self-evident principles. In the wake of John Locke’s empiricism, the science of ethics took a more experiential turn. David Hume sought to provide a causal description of moral sentiments, Jeremy Bentham offered an empirical test of right and wrong through the utilitarian calculus of pleasure and pain, while Herbert Spencer endeavored to ground ethics on natural evolution. As Hunter and Nedelisky ably tell the story, all these attempts eventually foundered by the onset of the twentieth century. The decisive strike was G.E. Moore’s objection that the scientific approach to morals wrongly supposes that an empirically observable property can be defined as something good—a move he called the naturalistic fallacy.

For the next seven decades, the science of morality laid dormant until E.O. Wilson broached the idea of applying genetics to human behavior in his 1975 book, Sociobiology: The New Synthesis. The new science of morality that consequently arose is very nicely encapsulated by Hunter and Nedelisky as combining four elements of its older counterpart. First, it embraces Hume’s claim that ethics is a matter of sentiment rather than reason. When people assert, in other words, that murder is wrong, they are expressing their feelings and emotions instead of cognizing some inherent feature of the act. Jonathan Haidt (The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. New York: Pantheon Books, 2012, pp. 3-92) is among the more notable advocates of this view today. Second, the new science of morality accepts Bentham’s utilitarianism as the criterion for ethical judgement. Steven Pinker (Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress. New York: Penguin Books, 2019) figures prominently here with his recent defense of Enlightenment values on the grounds that these have made people better off. Third, the new science of morals reflects Spencer’s emphasis on evolution, though now on a neo-Darwinian footing that explains morality as a set of behavioral tendencies that were encoded into our DNA by enabling our ancestors to transmit their genes to future generations. The concepts of kin selection and reciprocal altruism weigh heavily here in explaining people’s willingness to make sacrifices for the interests of others. Kin selection asserts that we are hard-wired to care for our relatives, while reciprocal altruism holds that we are disposed to help those outside our family circle in order to have the favor returned when we need assistance. And, fourth, the current scientific approach espouses the philosophy of naturalism advanced according to which our knowledge is limited to what can be empirically observed.

While Hunter and Nedelisky concede that the scientific approach has generated some valuable insights, they argue that it has ended up undermining the very goal that prompted its undertaking. That goal was to identify what morality is, but all that has been produced are accounts of how people are instigated to act in ways that are generally perceived as moral. It is one thing, Hunter and Nedelisky maintain, to identify the evolutionary and neural factors that cause individuals to help their fellows in need; it is quite another thing to prove that giving such help is morally obligatory. Their most serious charge, however, is that the science of morality leads to nihilism. Its practitioners will, in their more exuberant moments, profess the hope of arriving at an objective conception of morality. But in their more considered reflections, as Hunter and Nedelisky detail with several quotes, the purveyors of today’s moral science admit that they cannot demonstrate the truth about ethics and can only offer guidance on how to most effectively realize widely accepted norms. What began as the search for the ground of morality has devolved into the view that, “any course of action is, intrinsically, as good or bad as any other” (p. 183).

Hunter and Nedelisky provide good evidence of having caught the leading scientists of morality in the act of confessing to the non-objectivity of morality. Yet one might legitimately ask whether they are logically compelled to do that. Hunter and Nedelisky’s critique hinges on the claim that knowing the causes of moral action cannot possibly allow us to know morality itself. This claim, though, presumes that one cannot go from what is observable in reality, namely the causes of moral action, to what ideally would be observed in reality, namely action in line with morality. Put more simply, the underlying assumption is that “ought” cannot be derived from “is,” a well-known philosophic dictum originally set forth by Hume which Hunter and Nedelisky never question, except to note that not everyone has been persuaded by it as to preclude a science of morality. It is worth remembering, though, that chief among those who did not let the ought-is dilemma get in the way of attempting to develop a science of morality was Hume himself.

Figuring out why Hume persisted helps us understand where Hunter and Nedelisky go astray. Though Hume conceded that moral principles cannot be designated as true or false, he did think they are associated with sentiments and emotions in such a way that they can be effectively obligatory. A person may be tempted to kill their enemy, but if their feelings rebel in horror against the idea, then that person will be compelled to believe that murder ought not to be committed. This is to say that moral obligation is psychologically obliged instead of being rationally ascertained. The problem of deriving “ought” from “is” gets avoided by recognizing that the “ought” resides within the “is.” Indeed, for Hume the “ought” must be emotionally enforced inasmuch as he holds reason to be a servant of the passions.

Now if this is how reason actually operates—and there is plausible evidence in favor of this view—then the nihilism charge also fails. For it would not be the case that anything can ultimately be good or bad. Our emotional constitution will powerfully incline us to certain types of conduct and our intellects will support that disposition. Nor can this intellectual support be dismissed as a mere rationalization of our emotions. When an evolutionary dimension is added to Hume’s theory of mind, then the moral impulses can be seen as having undergone a continuous adjustment to the external conditions of our species’ development—a point made by Spencer. The correspondence of our moral feelings with reality is, therefore, not out of the question.

To be sure, the practitioners of today’s moral science have not availed themselves of these potential defenses. As such, Hunter and Nedelisky have done us the valuable service of exposing crucial weaknesses in the science of morality. Practitioners of this science need to bolster their arguments.

| Other Independent Review articles by George Bragues | ||

| Fall 2020 | Herbert Spencer’s Principle of Equal Freedom: Is It Well Grounded? | |

| Winter 2011/12 | Portugal’s Plight: The Role of Social Democracy | |

| Fall 2009 | You and the State: A Fairly Brief Introduction to Political Philosophy | |

| [View All (4)] | ||