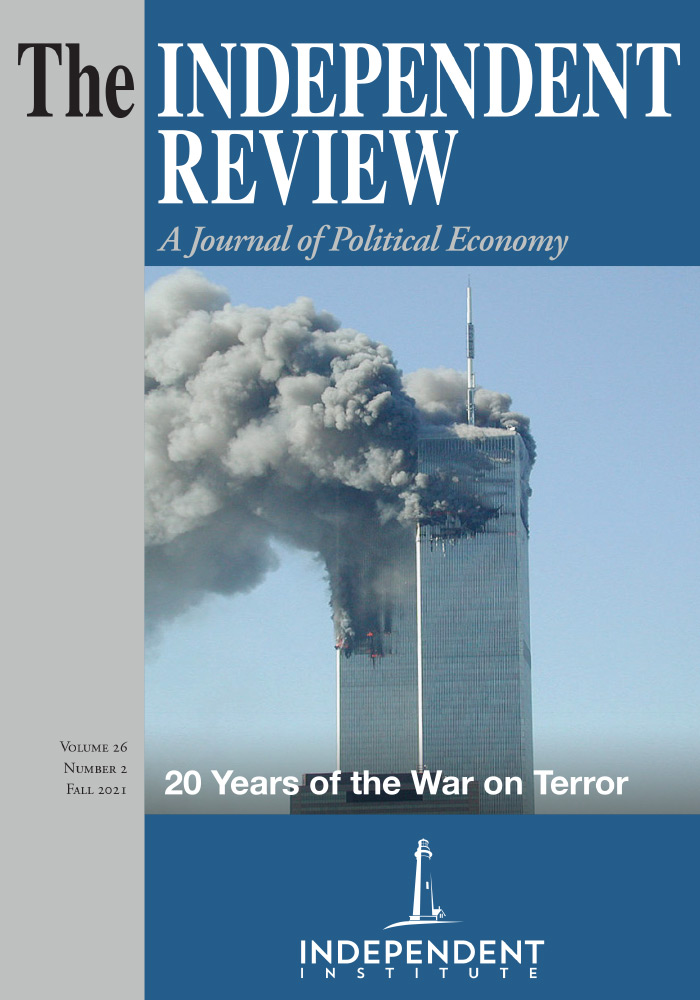

Garett Jones’s 10% Less Democracy proposes a series of provocative reforms to political institutions that would reduce the scope of democracy in public decision making, while also improving policy outcomes. The book combines summaries of mainstream academic research with contrarian interpretations of how democracy functions best in practice. Jones demonstrates unequivocally that certain elements of today’s governance structures are uncontroversially desirable, yet if you step back to consider them, they are also anti-democratic. There is an underlying logic to all the reforms Jones advocates and—in a move that is very effective rhetorically—he makes it difficult to approve of the anodyne non-democratic governance structures of the status quo, while also categorically rejecting his more radical recommendations for reform.

In Chapter 1, Jones gives his argument its foundation. He is not advocating autocracy. Democracy seems to prevent famines, as Amartya Sen has found, and democratic governments rarely kill their citizens on a large scale. However, Jones suggests there can be a “Laffer curve” for democracy, and the United States and other countries like it may be on the “wrong” side of the curve. While Jones points to Robert Barro’s work in the 1990s that there is a Laffer curve relationship between democracy and economic performance, he ultimately concludes that modern research has not reproduced this finding, rather finding a “muddle” of results without a clear interpretation (p. 22). Jones suggests instead to look at the particular ways countries can become marginally less democratic, in order to provide “microfoundations” (p. 25) to answer the question, with this being the main focus of the book.

But even in the scope of this preliminary framing, specialists in the field would likely respond that the empirical case for democracy is far stronger than Jones conveys it to be. The strongest recent literature review I have come across is by Marco Colagrossi, Domenico Rossignoli, and Mario A. Maggioni (2020. “Does Democracy Cause Growth? A Meta-Analysis of 2000 Regressions.” European Journal of Political Economy 61 [January], no. 101824), who find (a) clearly positive results that cannot be explained by publication bias, (b) that more recent research shows more consistently stronger results for democracy, and (c) that disagreements among studies were driven by differences in which samples had been used. Jones also takes issue with a recent paper by Daron Acemoglu, Suresh Naidu, Pascual Restropo, and James A. Robinson (2019. “Democracy Does Cause Growth.” Journal of Political Economy 127 [February]: 47-100) on the grounds that it uses a dichotomous measure which by nature cannot capture what he is describing, but there are many measures that allow for considerable nuance (for a review the methods, see Klaus Grundler and Tommy Krieger, “Using Machine Learning for Measuring Democracy: A Practitioners Guide and a New Updated Dataset for 186 Countries from 1919 to 2019,” European Journal of Political Economy [Forthcoming]), and in any case, there is disagreement in the literature of what the correct approach is. If Jones dislikes how democracy is measured, as he briefly indicates (pp. 18 – 19), there are plenty of alternatives. (I will return to this point towards the end of the essay.)

Setting aside the broader literature on the effects of democracy, Jones may still be correct in his details. In three chapters that follow, his initial examples of reforms may be read as essentially uncontroversial: whether we would be better off with longer terms for legislators, the benefits of central bank independence, and that appointed judges, city treasurers, and regulators perform better than elected judges, city treasurers, and regulators. The public or most social scientists may not even consider that changes in these directions would qualify as movements away from democracy, though Jones argues convincingly that they do. He is also able to marshal a fair amount of empirical evidence in favor of the benefits of these reforms, and his claims are very firmly in the mainstream, especially when it comes to central bank independence and appointed judges. At the end of chapter 4 he raises a more extreme proposal, but one previously made by Alan Blinder, that there should be a panel of economists running the details of fiscal policy (i.e., how to most efficiently raise a certain amount of revenue), after they receive broad guidelines from the legislature, all running in parallel to how independent central banks function (p. 91–94).

The fifth chapter, because of its controversial content, is titled “This Chapter Does Not Apply to Your Country” and covers shifting political power towards informed voters (including limiting suffrage), i.e., epistocracy. Its content is the most directly comparable portion of 10% Less Democracy to Against Democracy (Jason Brennan. 2016. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press). However, the two books spend their time on much different topics. Brennan’s emphasis is on dethroning democracy as itself an ideal, and discrediting the advocates of “deliberative democracy” who portray democracy as something it is not. Brennan’s proposals, generally speaking, involve a grand reimagining of our political institutions towards epistocracy.

In contrast, the approach of Jones in chapter 5 is an emphasis on institutions and rules that already exist in the world, and as such should not be thought of as potentially extreme as what Brennan advocates. Jones points to the somewhat shocking fact that sixteen European countries already take away voting rights from people who have mental illnesses or intellectual disabilities—and the United States isn’t the only country with a modern democracy to take the right to vote away from felons. Three seats in Ireland’s upper house are reserved for graduates of Ireland’s elite universities. These suggestions (which also include requiring a level of educational attainment for voting rights) are the most controversial aspects of the book, but don’t worry: this chapter does not apply to your country.

Jones follows the controversial chapter 5 with a pair of contrarian arguments concerning how to achieve high quality governance. The first is that bondholders and global financial markets are useful in guiding governments to better policies via the provision of rapid feedback to policy decisions through price signals in financial markets. Effectively, bondholders function as unelected bureaucrats and advisors who can walk away from their stake in a country at any time, and the withdrawal of their support is a swift kick in the pants to any country veering off course. We should invite bondholders to have a less informal seat at the table, and more provocatively, Jones suggests that bondholders get explicit representation in the upper house of the legislative branch.

Jones then defends the practices of transactional politics. Such politics are thought of as corrupt, but Jones argues that vote trading and earmarks are what make democratic political institutions function at all. As earmarks have declined, the focus in politics has become less about deal-making and policy and more about what plays well in social media. Since the political machines that facilitate deal-making are also about insulating politicians from voter backlash, moving back in the direction of the political machine can also be seen as a movement against democracy. Yet, perhaps it could also make democracy function better.

The main text of the book closes with a pair of case studies. Jones first takes on the case of the European Union, which in common conversation, is criticized on the grounds that it is anti-democratic, but Jones argues that the technocratic elements (like the ECB) have been run competently; it is the democratic elements that are to blame (Jones points to the incoherent response to the 2015 refugee crisis as a democratic failure). Then, Jones holds up Singapore as an extreme expression of what he advocates—50% less democracy instead of 10% less democracy. But besides somewhat suspect democratic credentials, conventionally defined, Singapore also possesses elements of what Jones has spent the book endorsing: a highly educated electorate, an independent judiciary, very long-time horizons in the public sector, and a highly effective political machine running Singapore’s “democracy.”

Before concluding, I have a few remarks about 10% Less Democracy. The first is that Jones has identified certain dimensions of democracy that are not considered by scholars who measure democracy (e.g., Freedom House or the Polity Project). And these dimensions clearly belong. Indexes of democracy begin by measuring the obvious things to determine whether a country is a democracy—who can vote and whether elections are fair. But some measures can use a very expansive definition, including measures of civil society or the rule of law. The kinds of variables that Jones describes, such as the length of terms for legislators or whether certain decisions are insulated from politics, are at an intermediate step between the two extremes. The “anti-democratic” reforms Jones wishes to make deal with concepts that are less core to the idea of democracy than whether an “election” was faked by a dictator, but closer to the core than what is often measured as a characteristic of democratic political institutions. Jones has also documented that there are demonstrable differences across countries on these margins. That means that variables like central bank independence deserve to be somewhere in at least some of these indexes of democracy, and currently they are not.

Having said all that, with relatively little effort, I have created a way of measuring anti-democratic institutions by country with an emphasis on keeping power in the hands of elites, if not specifics like central bank independence. The Varieties of Democracy project is a vast data set that has many measures of democracy, including “Polyarchy,” which is their baseline measure of general democratic institutions, and “Participatory Democracy.” Participatory democracy is a combination of polyarchy and a “Participatory Component Index,” containing four variables: civil society participation, direct popular vote, elected local government power, and elected regional government power.

I took this data and looked at the countries that had especially high or low values of the participatory component index given their level of polyarchy/democracy. (More precisely, I ranked countries using the residuals from a regression of the two variables.) The countries that are especially anti-participatory are Eritrea, Saudi Arabia, Turkmenistan, Qatar, Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates, Equatorial Guinea, Singapore, Iran, and North Korea. The countries that are especially participatory are Switzerland, Uruguay, Italy, Taiwan, New Zealand, Lithuania, Romania, Bulgaria, Denmark, and Slovenia. Perhaps one may wish to quibble with the exact content of the participatory component index, but the results look approximately correct in measuring keeping power in the hands of the elites and away from the masses. Yet the first list is, at best, a mixed bag. All this is to say, Jones ought to be able to test his hypothesis in cross-country regressions, and not simply focus on particular “microfoundations;” I was able to put together this measure with very little effort.

The second issue I want to raise is that there is an unaddressed tension between the works of Jones, Brennan (2016), and others and a recent strand in classical liberal thought which sees the development of the administrative state and the use of expert judgment as affronts to democracy or even basic conceptions of equality before the law (see David Levy and Sandra Peart. 2016. Escape From Democracy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; Roger Koppl. 2018. Expert Failure. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; Peter Boettke. 2018. “Economics and Public Administration.” Southern Economic Journal [April]). My reading of 10% Less Democracy and similar works is that the development of the administrative state detached from politics and the application of expert judgment are things to be welcomed, in part because of the ways they are anti-democratic. Perhaps I am mistaken, but to my knowledge, there hasn’t been a direct confrontation of Jones or Brennan to the philosophical and political economy arguments of the classical liberals, or a direct confrontation of the classical liberals to the empirical arguments made by Jones and Brennan. The literature in this space is missing important pieces until such confrontations take place.

10% Less Democracy is an easy, contrarian read with some pills that are easier to swallow than others. What Jones shows most convincingly is that there are very particular margins, such as central bank independence, where virtually every informed observer already believes that the less democratic institutional arrangement yields more desirable outcomes. But do we want ten percent less democracy? While the margins of democracy Jones highlights are almost certainly overlooked by other scholars, he has not made the argument that they capture the most common differences in political institutions across countries as they exist in the world today. We do not want 10% less fair elections, for example. Perhaps we should want a few percentage points less of democracy, but chosen very, very carefully.

| Other Independent Review articles by Ryan H. Murphy | ||

| Winter 2023/24 | Singapore’s Small Development State | |

| Fall 2018 | The Best Cases of “Actually Existing Socialism” | |

| Fall 2018 | Reply to Michael C. Munger | |

| [View All (5)] | ||