Networks are everywhere, in all aspects of the polity, the economy, and in social systems. Social historians are learning how to find them in historical data, where they have been hiding in plain sight; but understanding how these complex network patterns shape long-term cultural and institutional change requires proper analytical tools and programming capabilities that are only now becoming available.

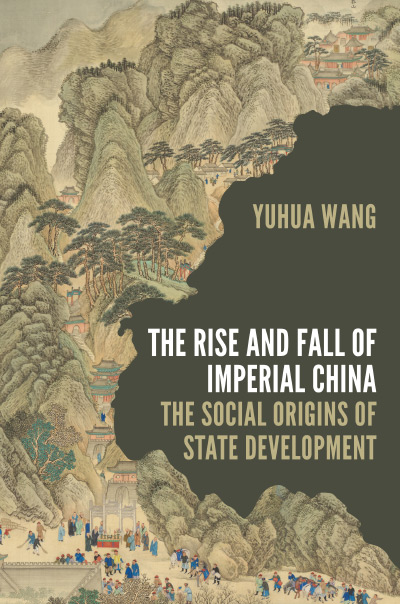

Yuhua Wang proposes that the steady-state equilibria created by social networks can explain the rise and fall of Imperial China over two millennia (p. 12). Understanding the distinctive network topologies of “elite social terrains,” he tells us, can help solve a puzzle in Chinese imperial history that has never properly been explained: namely that emperors who ruled over a strong state rarely held on to power as long as did emperors who presided over a weak one (p. 5). He lays out his theoretical argument in Chapter 1, attaching it to a conventional narrative that is highly informative to readers not familiar with Chinese history.

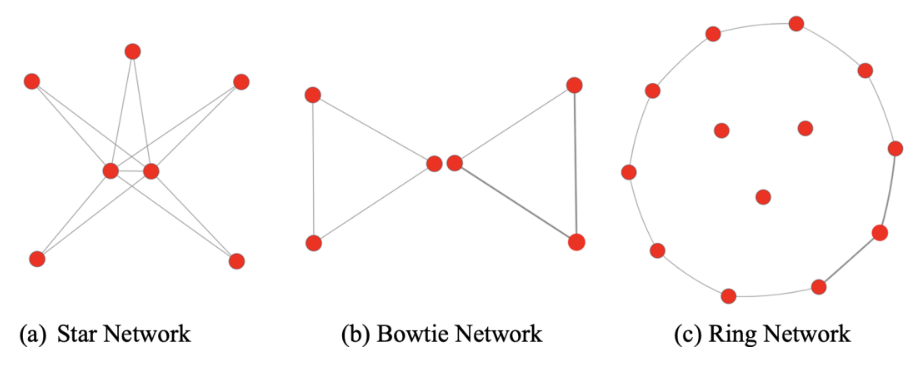

But what follows in the book is an analysis too grounded in theoretical models that have no counterparts in either the natural world or human history. He presents three network equilibria “ideal types of elite social terrains,” that characterize the arc of Chinese history from the earliest dynasties to the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1911. The first is a star network, which corresponds to a strong state and weak society, and characterizes the Chinese imperium during the Tang era (618 – 907). Next is the book’s principal actor, a bowtie network, corresponding to a strong society and weak state, and illustrating the state – society partnership that endured from the mid-tenth to the mid-nineteenth century. Finally, a ring network, during the period of state weakening under warlords, spanned the mid-nineteenth century until the fall of the empire in the early twentieth century. The three graphs look like this:

Figure 1. From p. 8, The Rise and Fall of Imperial China: The Social Origins of State Development, Yuhua Wang, Princeton University Press, 2022.

As much as Wang’s theoretical claims may hold first-blush appeal, their application to established network theory, in physics, chemistry, economics, and political economy, remains problematic. And they ignore important aspects of Chinese history itself. With the exception of Ronald Burt’s 1992 study of structural holes, the book offers no reference to recent discoveries in network science. Strong state, weak state—neither is an effective proxy to gauge the essential property of system stability. Missing from Wang’s approach is an explanation of the dynamical processes acting on the network’s structural makeup (its topology). More important, he fails to provide a metric of the imperial system’s underlying resilience to explain how its failure dynamics link to the topology.

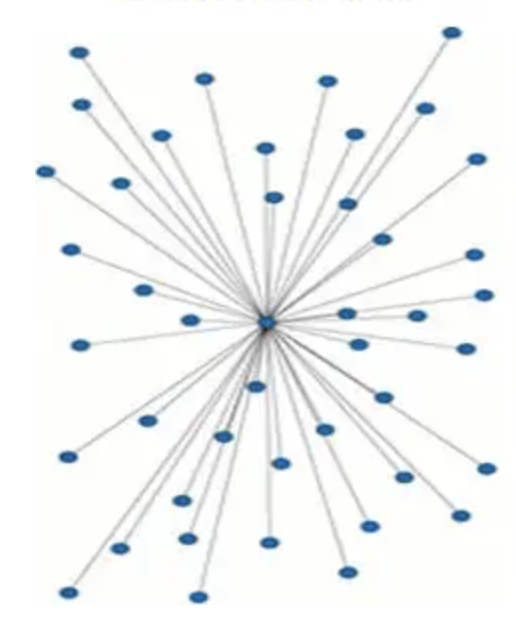

For example, notice that the star network has two central nodes connected by an edge, or bridge. Wang does not identify the second of the two central nodes. Even so, this graph mispresents the central feature of the Chinese political structure, that it was a centralized hierarchy with a single emperor as the sole central node. The degree of centralization wasthe system's essential stability attribute. Deletion of the central node would cause the connectivity of the secondary nodes to disintegrate, and would vitiate the efforts of successive dynasties to build a network (the state bureaucracy) that would connect the entire empire via a single ideology. Moreover, those secondary nodes had few if any links to one another, a practice established by imperial design. Figure 2 maps the network structure as a centralized hierarchy, and more accurately reveals both the stability properties of the system and its robustness to attacks or accidents—yet nothing like it appears in the book.

Figure 2.

Next we encounter the book’s principal actor, the bowtie network, upon which rests Wang’s argument about the relative strength of the state. This endemic (closed) equilibrium represents a status quo, we are told, that was uninterrupted by dynamic inconsistences for a millennium. Unfortunately, the design is improbable. The two triangles, or triads, from which the bowtie is constructed are not connected. In other words, there is no linkage of the central elites to one another. A bow tie may be a subgraph, and indeed one of several hundreds of possible subgraphs, but it is not a structure that is likely to occur in government, politics or large social structures. It is more likely to appear in friendship networks, as its underlying instability prevents it from serving as a foundation for trust, financial transactions or trade. It would only require a single additional triad for the bow tie to lose its structure and morph into something else.

The third graph, a ring network, is the most improbable of the set on account of its wholly theoretical conception. These structures virtually never appear in nature, much less in complex societies, and China was a complex society for several millennia. The ring network more likely conforms to the ecology of small, isolated, hunter-gatherer societies. Since the ring graph reveals no connectivity of the elites in the center with peripheral nodes, it cannot function as a “network” so much as a collection of remote local communities. Historians, Wang reminds us, report that political power shifted from central elites to local elites in the late nineteenth century. But this graph depicts no links at all between significant nodes (warlords) that might represent the real-world situation characterized by those who swore an oath of loyalty to each other (“Not born on the same day, we will die on the same day”) and later pledged allegiance to Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek. Again, we are missing models and analysis to explain how one topology transitions to another.

To produce graphs that are sound descriptions of reality, we need to understand the processes of self-organization that not only gave rise to a network’s structural properties, but also cause the transition from one network structure to another. What are the dynamical processes perpetually acting on the topology, and how do interactions and feedback alter both its structures and large- and small-scale dynamical processes. For this it would be helpful to know more about the learning processes of decentralized agent interactions. What is driving attraction overtime, is there an evolutionary force like kin selection or group selection at play? How much does ideology, lineage, occupation or location apply in forming a common affiliation? What do the nodes represent—positions in the governmental hierarchy, e.g., governors, magistrates, degree holders, wealthy landlords, members of the military, court eunuchs, merchants, or possibly religious leaders? How do “terrains” or “topologies” create an equilibrium? Wouldn’t the patterns of their connections continually evolve as new linkages form, and as some nodes acquire more linkages than others? Such inevitabilities would cause the entire structure to transform as some nodes become hubs, acquiring more connections than rivals. We should expect events or attractors that cause certain nodes to become connectors over time to engender rivalry among elites, enough to cause the network topology of a decentralized hierarchy to be in constant transformation.

Wang’s assessment holds promise but appears premature, relying too much on idealized, closed-form equilibrium models of network typology that have no analogue in nature or history. The macroscopic patterns of these structures arise from arbitrary closures, equilibrium, rational expectations and decisions made in a cultural vacuum, in which actors “know” the probability distributions of their actions ex ante. Models that take into account heterogenous agents, interdependence and adaptation in response to continuous feedback between agents and their environments would provide greater insights into the bottom-up dynamics that give rise to a system’s emergent qualities, the classes of nodes and links that define them, and the typical behaviors and anomalies that may arise. These models will show Wang and others a more realistic understanding of the evolutionary dynamics of historically based network systems.

| Other Independent Review articles by Hilton L. Root | |

| Summer 2020 | Has the West Lost It? |

| Winter 2018/19 | The Invisible Hand?: How Market Economies Have Emerged |

| Spring 2001 | Do Strong Governments Produce Strong Economies? |