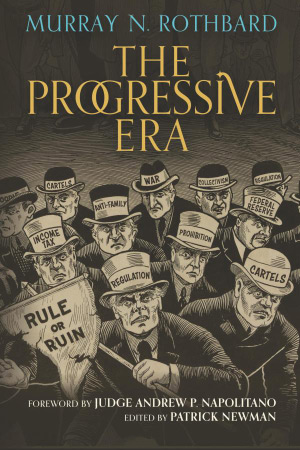

An edited manuscript about the Progressive Era, which Murray Rothbard began writing in the 1970s but did not manage to finish by the time of his death in 1995, at first sight makes for a strange publication in 2017. Picking it up as an unexpected addition to my summer reading, I certainly felt so. Yet, I have found it to be both timely and pertinent. The main themes of the book—popular and regulatory attitudes towards large and influential corporations (and our understanding of both monopoly theory and cronyism), ethnoreligious conflicts and migration issues, identity politics, tariffs and protectionism—have their parallels in many contentious contemporary political issues, both in the United States and many other countries.

The Progressive Era is an erudite book which covers a century of American history (roughly from the 1830s to the 1930s). It gives an ontological account of progressivism as an increasingly interventionist trend in public policy—which by Rothbard’s account gradually emerged in the second half of the nineteenth century and prevailed as the dominant paradigm by the 1890s. Rothbard sets out to explain the factors by which this trend gradually emerged and then prevailed to become the dominant paradigm in American public policy. He makes the case that:

[this] broader period marks an era in which the entire American polity—from economics to urban planning to medicine to social work to the licensing of professions to the ideology of intellectuals—was transformed from a roughly laissez-faire system based on individual rights to one of state planning and control (p. 295).

The reader encounters a two-pronged argument. The first part outlines the economic forces at work, based on a distinctly Austrian understanding of market competition—one where, in the absence of entry barriers, the market is expected to be dynamically self-correcting, and even a firm with a hundred percent market share is not seen as a true monopolist, since it must always act in expectation of potential competitors (i.e., it cannot sustainably set prices above what other potential entrants could profitably offer the same service at). This is a direct challenge to the mainstream narrative, which suggests that progressivism did away with the (supposedly) unbridled capitalism of the Gilded Age, when “robber barons” cartelized industry after industry into exploitative monopolies and cartels. Whereas the popular narrative is one of market competition failing and government stepping in to break up the cartels and enable fair competition, Rothbard makes the exact opposite case. That it was government intervention which enabled cartelization and monopolization; practices which up until then were certainly attempted, but always remained unsustainable business models that market competition penalized. It was progressivism which “re-created the age-old alliance between Big Government, large business firms, and opinion-molding intellectuals” (p. 318), and facilitated the entrenchment of monopolies and cartels as profitable and viable business models. It was only after Big Government shielded it from market competition that Big Business was able to abuse its market position.

To make his case Rothbard weaves together a light theoretical touch with an abundance of mini case studies: of railroad companies, the petroleum industry, the iron and steel industry, and the agricultural machinery industry. He points out that attempts at cartelization without government intervention faltered time and time again. Ironically, even aspects of the market process often seen as “failures,” such as information asymmetry, are shown to have contributed to, rather than detracted from this. Such is the example of rebates which railroads used secretly, after having agreed on fixed prices with other cartelists. Each of the cartelists had an incentive to undercut prices below the agreed upon rate, they did this with secret rebates, thereby eroding the stability of the cartel (pp. 56-66). Once they successfully lobbied the government to ban rebates, this avenue of market competition was closed, and cartelization could be more stable than before.

Although it is my assessment that the book shines brightest in these first three chapters, the second prong of the argument, the cultural-political part, is actually the one to which Rothbard dedicates most of the book. He explores the ideological basis of progressivism and its connection to religious affiliation, ethnic origin, and even gender. Rothbard proposes that Postmillennialism—the belief of American Protestants that through a moral life and a millennium of societal progress the second coming of Jesus Christ will be brought about—was a key ideological driver of progressivism. It motivated the use of the state apparatus as a means of attempting to ensure both that individuals led a moral life and that society achieved progress; the state was to bring about Heaven on Earth.

Most of these intellectuals, of whatever strand or occupation, were either dedicated, messianic postmillennial pietists or else former pietists, born in a deeply pietist home, who, though now secularized, still possessed an intense messianic belief in national and world salvation through Big Government. But, in addition, oddly but characteristically, most combined in their thought and agitation messianic moral or religious fervor with an empirical, allegedly “value-free,” and strictly “scientific” devotion to social science. Whether it be the medical profession’s combined scientific and moralistic devotion to stamping out sin or a similar position among economists or philosophers, this blend is typical of progressive intellectuals (p. 399).

Throughout, the author’s tone resembles that of a prosecutor before a jury. With progressivism being on trial for bringing about a corporate state capture, cronyism. And the mountain of evidence Rothbard presents certainly casts a damning shadow over the progressive venture. All of the case studies could essentially be summarized as the government causing a problem, then making it increasingly worse by attempting to solve it (or, in any case, at least pretending to be doing so, but more likely being operated by interest groups which had everything but fair competition in mind). While the prosecutor’s tone is effective in the first part of the argument, where Rothbard shows intervention turned out to be an inefficient, counterproductive means for achieving the fair competition it purported to want to achieve—it is somewhat less persuasive in the cultural-political part.

The hypotheses Rothbard offers about the ethnoreligious origins of progressivism are certainly plausible. The connections he makes to racially motivated and eugenics policies have been well corroborated by more recent research too (see Thomas C. Leonard Illiberal Reformers Race, Eugenics, and American Economics in the Progressive Era, Princeton University Press, 2016) as have the ideological changes among the intelligentsia and in particular their connection to a distinctly positivist view of social science emanating from Germany at the time (see, for instance, Daniel T. Rodgers, Atlantic Crossings: Social Politics in a Progressive Age, Belknap Press, 2000). However, the case studies used to support this cultural-political part of the argument will leave the reader wanting. Rothbard identifies numerous correlations (using voting records, population statistics, etc.), yet this analysis is left at the level of eye-ball econometrics. He makes no attempt to report the strength of the various correlations, the sizes of the effects he postulates, or to consider other potentially competing explanatory variables and how they stack up to those he proposes. Complex issues such as women’s suffrage, for example, are presented as straightforward, mono-causal affairs, in the service of the postmillennial agenda. Here the prosecutor’s tone shows a dark side, for it is clear Rothbard feels his job is to support his (at times speculative) case, not to play his own opposition and try to answer potential competing theories and explanations regarding the phenomena he discusses.

Both parts of the argument come together in a way that is very reminiscent of Bruce Yandle’s classic Bootleggers and Baptists argument of predatory business actors forming coalitions with paternalistic (or gullible) do-gooders to bring about regulation which is socially costly, as was the case during the Prohibition Era, which is a key focal point for both Yandle and Rothbard. (See Adam Smith and Bruce Yandle Bootleggers and Baptists: How Economic Forces and Moral Persuasion Interact to Shape Regulatory Politics, Cato Institute, 2014.) Added to this is the argument of (ab)using crises to propel the growth of government, as was the case during and after World War I, which is an argument Rothbard’s book shares with Robert Higgs’s Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government (Oxford University Press, 1987), which he cites favorably.

The Progressive Era is a book of impressive breadth. It is a sweeping criticism of progressivism supported by mini case studies on everything from the early development of railroad companies and their entanglement with politics (seen in the emergence of subsidies, land regulation, and price fixing), to migration restrictions, ideologically motivated obligatory schooling, and even the American suffrage movement. Its breadth is both a strength and a weakness, however. Rather than becoming the definitive work on the period, the book has the potential of becoming a great source of inspiration for contemporary scholars—where Rothbard stopped at eye-ball econometrics, or failed to consider competing explanations, current scholars can easily find room to contribute to the discussion. Especially given the strength of the parallels between progressivism then and progressivism now.