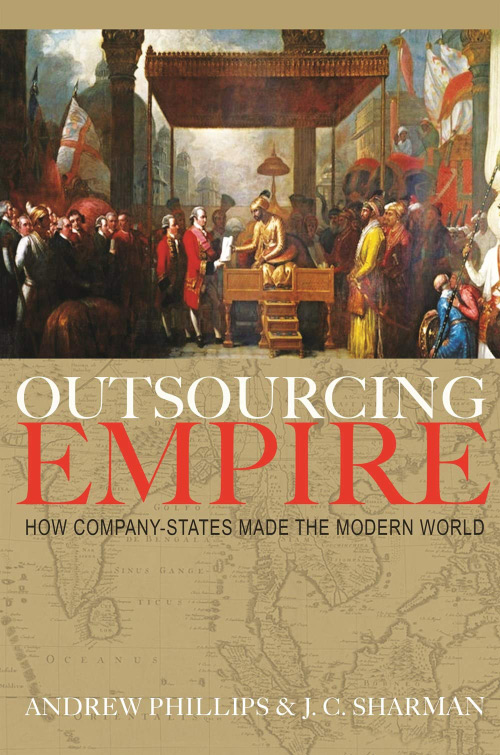

The distinction between the public and private domains is something we often take for granted today, particularly in the West. Andrew Phillips and J. C. Sharman’s book Outsourcing Empire: How Company-States Made the Modern World illuminates how the history of these two domains, in particular their past hybridization, laid the foundations for our modern world. The specific hybridization of the public and private spheres the authors consider is known as the “company-state,” an institution with the power of a king and the financial promise of a transoceanic merchant enterprise.

In the early seventeenth century, European powers faced both increased geopolitical and military competition. To financially facilitate these challenges, they sought to further expand their spheres of influence by obtaining control over non-European resources. Due in large part to principal-agent problems, European rulers did not have the institutional means by which they could extend their power across continents. Thus, the company-state emerged. These new institutional experiments began from “the early 1600s as the most prominent and consequential means of bridging this gap between rulers’ grasp and their reach” (p. 10). Phillips and Sharman document the economic, political, and societal factors that led to the rise, persistence, and eventual decline of the company-state.

Company-states were hybrid public/private institutions in a time when hard distinctions between public and private domains did not exist. They offered a timely mix of characteristics that flourished at a very particular “historical juncture in Western Europe’s development” (p. 17). European rulers, in particular the English and Dutch, wanted to combine the financial capital of a merchant enterprise with the power of a sovereign. Phillips and Sharman discuss the range of institutional advantages that made company-states an attractive choice to meet the needs of European rulers at the beginning of the seventeenth century. These characteristics include their limited-liability corporate structure, ability to solve principal-agent problems, and in-house capacity to organize violence.

The corporation, started centuries earlier, offered the legal and constitutional foundations for the rise of the company-state. The company-state’s joint-stock form and limited-liability corporate structure became definitive features that allowed it to invest large amounts of capital in risky overseas ventures. Its joint-stock structure, the authors note, “enabled investors to limit their liability in proportion to the assets invested, while providing them with a passive means of participating in and profiting from the company- states’ success” (p. 38). Company-states also separated ownership and management, which incentivized managers to prioritize long-run growth over profitability in the short-run. The Hudson Bay Company, which focused primarily on the fur trade in the Atlantic, has maintained continuous institutional existence from the 1600s to today. This institutional structure coupled with a government-backed monopoly charter gave company-states a tremendous competitive advantage over unincorporated merchants.

The most attractive trade routes at the time were from Europe to Asia. However, the high communication and transportation costs introduced myriad principal-agent problems. Commercial agents that were far away (as far as eighteen months’ travel) from their managers back in Europe were incentivized to engage in their own private trading endeavors and to ignore their employers’ instructions. To solve these problems, company-states employed institutional mechanisms to align the incentives of employers and those of their distant employees. The primary mechanismwas to extend sovereignty by dividing it among relevant parties. European rulers organized long-term trading monopolies through a royal charter that extended their powers of diplomacy, law making, and war to their agents. The rulers gave nonstate actors coercive privileges in exchange for capital gained from trade expansion. The most successful company-states, the English and Dutch East India Companies, “were the most important vehicles for Western Expansion in Asia” (p. 39), most notably because of their ability to overcome pervasive principal-agent problems by securing monopoly charters over trade with the East. The English East India Company (EIC) proved to be more successful than the Dutch East India Company (Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, VOC) at overcoming incentive-alignment challenges because it gave its agents more freedom to engage in private trade while also working with the EIC.

Company-states managed their own armed forces and engaged in war and treaty making. Some also minted their own currency and administered civil and criminal justice within their territories. The ability to internalize their protection costs gave many company-states an advantage over their private competition. Some company-states were notorious for their violence. The VOC regularly fought in military conflicts with the Dutch’s European neighbors, engaged in piracy, and decimated indigenous populations in the East, in particular the people of the Banda Islands. The Atlantic company-states, namely the Dutch West India Company and the Royal African Company, came to dominate the African slave trade. The Royal African Company “shipped more slaves than any other single European concern, around 188,000 individuals” (p. 85).

Company-states were pervasive across Europe for hundreds of years—at least one company-state was chartered by almost every major European leader—and their institutional reach was global. The authors summarize the success of the company-state as “an institution capable of financing, coordinating, establishing and managing militarized commercial monopolies on a transoceanic scale” (p. 62). These characteristics, along with the agreeable geopolitical climate of maritime Asia at the time, led to the success of these early institutions. The history of company-states is a balancing act between power and profit, and the eventual cost of maintaining their growing power as well as the emergence of certain powerful intellectual trends contributed to their decline.

Throughout the discussion of the rise and fall of company-states, two arguments pervade Outsourcing Empire. First, company-states were formed at specific places and times to solve particular institutional problems, so some elements of them have persisted, whereas others have been rendered obsolete. Second, company-states facilitated and fostered cross-cultural relations around the globe.

Phillips and Sharman thoroughly chronicle the environment in which the company-state rose and persisted and note the many contributions to its decline. One of the most prominent forces that led to the downfall of company-states was the rise of a universal system of positive international law. Company-states cultivated and maintained unique and individual arrangements with local leaders and merchants around the world in order to increase the ease of doing business. They were known for taking into account indigenous customs and local traditions. The rise of positivist international law eliminated these customized deals in favor of a Eurocentric and state-centric global international system. This new legal system, the authors note, unfortunately “allowed no meaningful concessions to indigenous customs and conceptions of legitimacy of the kind that had once underpinned company-states’ localized bargains” (p. 151). Under this global system, there was an increasing intolerance for institutions that muddied the private/public divide as these two spheres became more distinct. The formulation of the science of political economy also contributed to the decline of company-states. Political economists began to decry the corruption associated with monopolies in favor of an economy centered on voluntary exchange among individual rational actors.

The most provocative argument Phillips and Sharman make is their most emphatic claimthat Western military superiority was not the driving force of European expansion. The nature of the institutional structure of company-states incentivized these groups to cooperate with the indigenous peoples, which is contrary to the picture painted in many narratives on these early modern cross-cultural encounters. Phillips and Sharman note the incentives of the company-states: “Cost cutting company directors meanwhile jealously sought to minimize military and administrative overheads wherever possible. Given these constraints, the company-states had little choice but to rely on diplomatic dexterity over martial prowess to win local on-shore allies” (p. 205). The VOC, known in part for its brutality, learned indigenous vocabularies and respected local hierarchies. Its profit motive incentivized it to cooperate with Asian emperors in order to gain status and prestige. This knowledge and cultural capital allowed the VOC to conduct diplomacy and broker trade deals with local officials. Employees in the EIC participated in the rituals of their Asian trading partners to forge a more trusting relationship on which to build the company’s commercial and political partnerships. The Hudson Bay Company traded furs with the American Indians, and although both groups had little respect for the business traditions of the other, they nevertheless tapped into vast trading networks and facilitated a market that richly benefitted both the Europeans and American Indian tribes. The authors remark that in order “to preserve their commercial and physical viability the Europeans had to adapt to the non-Europeans at least as much as the other way around” (p. 101).

The authors address what could be argued as a resurrection of the traditional company-state in the nineteenth century; however, these newer institutions had only a small fraction of their predecessors’ power and influence. The second wave of companystates was much less robust and were economically and politically weaker than the first wave, in part because the company-states’ sovereignty was much more constrained.

Phillips and Sharman conclude by recapping their arguments and commenting on the company-states’ influence in the modern international system and on the potential for a resurgence of corporate sovereignty. Key contributions by Outsourcing Empire include, first, laying the historical context that brings to light the relevance of these important and previously neglected institutions on the global stage; second, emphasizing the critical role company-states played in mediating cross-cultural relations for hundreds of years around the world; and, last, demonstrating that company-states were the leaders of European and non-European economic, political, and cultural encounters that began our globalized and modern world.