This Executive Summary highlights the key findings and recommendations from the Policy Report, Beyond Homeless: Good Intentions, Bad Outcomes, Transformative Solutions and is part of Independent's Beyond Homeless initiative, which also includes the new documentary Beyond Homeless: Finding Hope.

Background

Homelessness is a substantial—and growing—problem in California, even as it declines in many other parts of the country. It is a growth not only in sheer numbers but also in visibility, with even well-to-do neighborhoods, such as Cupertino and parts of Orange County, experiencing the rise of tent cities—along with the crowded, unsanitary conditions that have fueled outbreaks of diseases otherwise rarely heard of in modern, developed nations.

Although homelessness has actually declined across the nation in recent years, falling from more than 647,000 in 2007 to approximately 568,000 in 2019 (a decline of more than 12 percent), it has continued to increase in California, from about 139,000 to more than 151,000 during the same period (a rise of nearly 9 percent). Despite the fact that California comprises only 12 percent of the nation’s population, it now contains 27 percent of the homeless population, 41 percent of those experiencing chronic homelessness, and 53 percent of those experiencing homelessness who are unsheltered. The 72 percent of people experiencing homelessness who are also unsheltered in California is the highest rate in the nation.

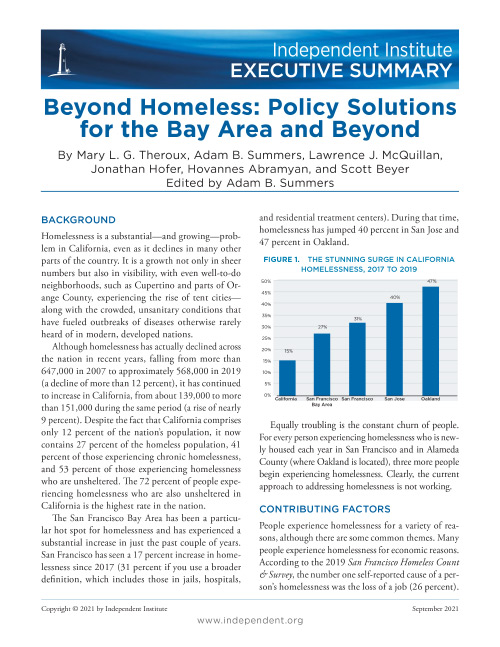

The San Francisco Bay Area has been a particular hot spot for homelessness and has experienced a substantial increase in just the past couple of years. San Francisco has seen a 17 percent increase in homelessness since 2017 (31 percent if you use a broader definition, which includes those in jails, hospitals, and residential treatment centers). During that time, homelessness has jumped 40 percent in San Jose and 47 percent in Oakland.

Equally troubling is the constant churn of people. For every person experiencing homelessness who is newly housed each year in San Francisco and in Alameda County (where Oakland is located), three more people begin experiencing homelessness. Clearly, the current approach to addressing homelessness is not working.

Contributing Factors

People experience homelessness for a variety of reasons, although there are some common themes. Many people experience homelessness for economic reasons. According to the 2019 San Francisco Homeless Count & Survey, the number one self-reported cause of a person’s homelessness was the loss of a job (26 percent). Alcohol or drug use was the second most common reason (18 percent), followed by more economic factors related to the inability to afford housing: eviction (13 percent) and being kicked out of one’s residence after an argument with family or friends (12 percent).

The high cost of living and, in particular, the lack of affordable housing in California (especially in the Bay Area) also plays a significant role. Unfortunately, many state and local policies intended to improve housing affordability—from affordable housing mandates to rent control to urban growth boundaries and other zoning restrictions—have unintended consequences that result in just the opposite. By making housing less profitable and limiting the amount of developable land, these policies ensure that less housing will be built (and that much of the housing that is built is higher-end, more expensive housing that is more likely to remain profitable), thereby pushing up prices on remaining housing units. This effect is compounded by prevailing wage mandates, high development impact fees, excessive environmental regulations and building codes, lengthy development approval processes, and litigation, all of which increase the cost of housing—and render many other potential developments unprofitable so that they are never built at all—and thus make housing less affordable.

Some causes of homelessness are more personal in nature. Alcohol and drug abuse was the second most commonly cited factor in the 2019 San Francisco homelessness survey, self-reported by 18 percent of all respondents and 24 percent of those experiencing chronic homelessness. And although many become homeless primarily because of their substance abuse, still others who began experiencing homelessness for other reasons succumb to substance abuse as a way to self-medicate and deal with the stress and depression resulting from their situations. Indeed, 42 percent of all individuals experiencing homelessness self-reported substance abuse, and 63 percent of those experiencing chronic homelessness reported alcohol or drug use. Some independent estimates range even higher.

Tragically, a staggering number of people on the streets also suffer from physical or mental disabilities—problems that hinder successful reintegration into the workforce and society at large. Nearly a third (31 percent) of those experiencing homelessness report having chronic health problems, and more than a quarter (27 percent) have a physical disability—including 15 percent who say they suffer from a traumatic brain injury. While 8 percent attribute their homelessness primarily to a mental health issue, 39 percent report a psychiatric or emotional condition, and 37 percent report having posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). About 9 percent of those experiencing chronic homelessness are military veterans.

In addition to the aforementioned factors, homelessness is exacerbated by a resigned public attitude toward it, as well as related troubling issues, such as open drug use and dealing on the streets and the widespread dangers of used drug needles, human feces, and other public filth. The increase in these conditions has made San Francisco the poster child for homelessness and the failure to deal effectively with the problem. Given the city’s generous public services; state laws such as Propositions 47 and 57, which essentially decriminalize public drug use and petty crime; and city policies institutionalizing street encampments, it should come as little surprise that people who wish to engage in such behavior—and take advantage of these services—gravitate to San Francisco. Indeed, nearly a third (30 percent) of those experiencing homelessness in the city came from other places.

The Housing First Approach

In recent years, federal, state, and local officials have shifted to addressing homelessness by adopting the “Housing First” approach to the problem. As the name implies, this approach emphasizes placing those experiencing homelessness in housing immediately, with the idea that access to supportive services and connections to the community-based supports people need to keep their housing and avoid returning to homelessness will follow. In practice, however, oftentimes such services are either not provided or not availed of by most residents. As a result, the underlying issues that led to their homelessness remain unaddressed, and many end up returning to homelessness.

To make matters worse, by dictating Housing First as the one-size-fits-all solution to homelessness, government agencies have effectively eliminated public funding for programs with alternative approaches. This has been especially punitive for the kinds of longer-term supportive programs that have been shown to help those experiencing homelessness achieve their full potential.

Moreover, permanent supportive housing (PSH) is correlated with only a very small immediate reduction in the homeless population, and even this effect disappears after one year. Using this approach, one would have to add at least 12.6 PSH beds to reduce the homeless population by one person in the long run. And because “affordable” housing developments in California are difficult to develop and can cost $500,000, $700,000, or even close to $1 million per unit, Housing First is unable to scale to the level that would be needed to house all of those experiencing homelessness, as Californians simply cannot afford to build a new home for every person experiencing homelessness who needs shelter. Even at the average going rate of $500,000 per unit for government-subsidized, low-income housing, and assuming we could build every unit needed right away, providing housing for the estimated 151,000 Californians currently experiencing homelessness would carry a price tag of more than $75 billion.

Although government policies oftentimes mandate Housing First policies, particularly for those with severe addiction or mental illness issues who are experiencing chronic homelessness, we reject this approach. Much, if not most, of the research on Housing First is either mixed, inconclusive, or does not support advocates’ narrative. Moreover, no person experiencing homelessness should be considered beyond help, and all are deserving of an active recovery program, if they so choose. Housing First may not be the best approach for many of those experiencing homelessness, who would choose, and benefit from, more transformational programs, including longer-term residential programs offering wraparound recovery services, workforce development, and other life skills that enable them to achieve their full potential. In fact, by establishing congregate developments housing individuals with continuing addiction or mental health challenges, and failing to treat each person experiencing homelessness as a unique individual with unique needs, Housing First diverts many of its participants from maximizing their human potential. Too often, Housing First means “death second” because people are merely warehoused and left to slowly die from their untreated addictions.

Harm Reduction

Housing First programs utilize a harm reduction approach to the treatment of substance abuse, which is oftentimes a significant factor leading to, or perpetuating, a person’s homelessness. Substance abuse is a serious issue in San Francisco, where there are more than 50 percent more injection drug users (about 24,500) than the number of high school students (nearly 16,000).

Harm reduction strategies that fail to provide individuals with recovery services, such as drug counselors or occupational therapists, may risk undermining recovery efforts.

Supervised injection facilities, syringe distribution, and needle exchange programs are common examples of harm reduction strategies. As San Francisco has discovered, however, failing to require that used needles be turned in can lead to significant medical waste problems. Only about two-thirds of the 5.8 million needles distributed by the city in 2018 were collected, leaving about 2 million needles unaccounted for.

The city also continues to struggle with a sharp increase in drug overdose deaths, which are now at record levels. Although 4,300 overdoses were reversed using naloxone in 2020, 712 people died of overdoses, a 175 percent increase just since 2018.

The harm reduction approach could also be seen during San Francisco’s implementation of the state’s Project Roomkey initiative to temporarily house individuals experiencing homelessness in hotel rooms during the coronavirus outbreak. The city drew harsh criticism when it was revealed that it was providing its new hotel residents with alcohol, tobacco, and drugs, and the discovery that at least one hotel room had been turned into a meth lab.

Harm reduction as currently implemented is lacking. Although it has shown marked success with curbing overdose deaths (as noted above, these figures remain high and have continued to increase in San Francisco but would be even greater without the use of naloxone) and blood-borne infectious diseases, harm reduction has yet to be demonstrated as a successful primary strategy for mitigating mental health issues associated with homelessness, reducing crime, or decreasing the rates of homelessness.

Spending More but Falling Further Behind

Governments across California are spending record amounts of taxpayer dollars on homelessness, yet the problem continues to grow. This indicates that the failure to adequately address homelessness is not due to a lack of government programs or insufficient taxpayer funding but rather to poorly designed policies and programs with the wrong priorities.

It is difficult to know exactly how many agencies, programs, and taxpayer dollars target homelessness because the programs overlap, intersect, and are opaque. As California Assemblyman David Chiu (D–San Francisco) admits, “No one today can tell me how much money is being spent on homelessness in California on all levels.”

In San Francisco alone, the city spent $365 million on homelessness in fiscal year 2019–20, an 84 percent increase in just the past six years. Adding in funding from the state and federal governments, along with contributions from private companies, foundations, and the approximately 100 Bay Area nonprofit organizations providing services to those experiencing homelessness pushes the total closer to $1 billion per year. In addition, the California Supreme Court’s September 2020 decision siding with proponents of Proposition C, a 2018 measure authorizing the city to impose a gross receipts tax on businesses with an annual revenue greater than $50 million in order to fund programs for those experiencing homelessness, will add another $250 million to $300 million per year.

But even with all this added funding and a proliferation of programs, homelessness surged 33 percent in San Francisco from fiscal year 2013–14 to FY 2019–20. Despite the city’s many goals to drastically reduce or end various types of homelessness, encampments are thriving, chronic homelessness is worse than ever, and families continue to experience homelessness in droves. But when the city misses a deadline to meet a goal to reduce homelessness, which occurs regularly, officials simply extend the target date and the money keeps flowing, with no accountability for failure. The more that programs fail, the more that taxpayer money is poured into them. Billions of dollars have been spent on well-intentioned programs staffed by sincere personnel; yet, as this homelessness-industrial complex has become more entrenched, homelessness has only gotten worse. It is time to implement and scale up alternative designs based on innovative approaches to better address homelessness in the San Francisco Bay Area and across California.

Alternative Models

There are numerous transformational programs across the country that provide evidence of the efficacy of expanded approaches to homelessness.

Step Denver has found success helping men experiencing homelessness overcome addiction with former leader Bob Coté’s original “no drugs, no booze, find a job” approach and its “Four Pillars for Success”: sobriety, work, accountability, and community. Through job training, addiction recovery talks, peer meetings, and, after six months in the program, off-site housing at sober living homes, Step Denver serves an average of 275 men each year and boasts an impressive graduation rate of 70 percent.

Another notable facility providing a model at scale is Haven for Hope in San Antonio, Texas. Its 22-acre campus offers a holistic array of services for those experiencing homelessness, as well as delivering services to as many as 5,000 individuals each month that prevent them from falling into homelessness.

Although Haven for Hope is primarily a transformational facility, it includes a low-barrier emergency shelter known as The Courtyard. This emergency facility provides a safe sleeping site as well as three hot meals daily, showers, laundry, mail service, health and mental health care, and outreach services. That alone has dramatically reduced the nighttime presence of those experiencing homelessness in downtown San Antonio.

Those staying in The Courtyard are urged to commit to recovery and enter Haven for Hope’s Transformational Campus, which offers long-term housing with no time limit and individualized supportive services for addiction recovery, education, life skills, and employment. It also offers childcare, legal services, health and mental health care, and animal kennels.

Since 2010, 5,002 people have exited the Transformational Campus to permanent housing, with 88 percent remaining stable after one year, and another 1,029 are living there now, working to make that shift.

Solutions for Change, based in San Diego County, focuses on families experiencing homelessness, particularly single mothers with children. It was built around a 1,000-day “empowerment academy” called Solutions University, offering participants access to a variety of job and life skills services and both on-site and off-campus transitional housing. The organization even has its own aquaponics farm, offering jobs to some participants, and maintains a real estate arm that builds permanent affordable housing for participants. In five years, Solutions University graduated roughly 800 families, positively affecting the lives of between 2,500 and 3,000 people. The recidivism rate for drug usage among program participants is 7 percent, compared with 74 percent for similar local organizations.

Unfortunately, because some Solutions for Change residents at one of the organization’s permanent supportive housing facilities received Section 8 rent subsidies, their participation in Solutions University and drug testing requirements violated state and federal Housing First mandates, and so the funding for those housing units was lost. Solutions for Change was forced to shut down Solutions University for residents at all of its permanent supportive housing facilities in the fall of 2020. (It had already had to forgo $600,000 a year in federal grants due to the same Housing First rules.) Solutions for Change continues to offer programming (along with drug testing and class participation requirements) through its revised 700-day Solutions Academy at its transitional housing facility on the main campus because that facility does not have the same issues with government funding.

Some services continue to be offered to the permanent housing residents on a voluntary basis, but participants can no longer benefit from the more intensive program and the former guarantee that recovering addicts will not have to live near others who are still using drugs or alcohol. This illustrates the dangers of accepting public funding and the corrupting influence of politics on such voluntary and humanitarian efforts.

Recommendations

Homelessness may seem to be an overwhelming problem, and many current policies and approaches have failed to effectively tackle it, but there are a number of things that can be done to help many more people overcome obstacles and get back on the path to achieving their full potential. Our recommendations generally fall into two main categories: those related to policies that address those currently experiencing homelessness and those related to housing policies that may affect homelessness rates and push more people into homelessness in the future.

Homelessness Policy Recommendations

- Direct resources based on demonstrated performance metrics and positive outcomes, regardless of the particular methods or approaches utilized to achieve success.

- Target the Housing First approach to those most likely to benefit from it. The Housing First model should also be revised to provide both more economical and more functional housing options, such as group homes and shared units, as opposed to individual units costing $500,000 to $900,000 plus annual operating expenses. The current one-size-fits-all approach is ineffective and crowds out more successful and promising approaches and programs.

- Improve tracking of program participants after they graduate from or leave programs and utilize quality-of-life performance measures and technology, such as computers/smartphones and electronic communication. This can help to address problems before they get to the point that people are forced to return to homelessness, and the feedback received can help to improve program design and services. These performance metrics should also be used to direct resources to successful programs.

- Educate the public about actual outcomes of various approaches and policies to build support for those programs that assist people experiencing homelessness, rather than those programs that exacerbate issues. Although we must be empathetic with and compassionate toward those experiencing homelessness, and understanding of the traumas they have experienced, there is nothing compassionate about allowing people to live in conditions that put them and the wider community in danger. Homelessness policies and approaches that worsen public drug dealing and use, encampments and street living, aggressive panhandling, and used drug needles, bodily waste, and other debris in public spaces perpetuate a degraded quality of life and community. Ultimately, life on the streets leads to premature death—not a compassionate outcome.

- Reexamine conservatorship laws, such as the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act of 1967, but consider conservatorship only in extreme cases, when people experiencing homelessness violate the rights of others by threatening their health and safety, particularly if they have diminished capacities for reason or understanding the consequences of their actions. Strict safeguards must accompany the use of conservatorship to protect individual liberties and prevent its abuse.

Housing Policy Recommendations

- Relax zoning restrictions, eliminate urban growth boundaries, and enhance property rights to allow the housing supply to meet the demand and improve housing affordability.

- Eliminate inclusionary zoning (affordable housing) requirements and rent controls to spur more housing production, reduce overall house and rent prices, and improve the quality of rental housing.

- Abolish prevailing wage laws, which increase average construction costs for affordable housing projects by between 10 percent and 25 percent—and raise total project costs by as much as 46 percent for market-rate housing in areas such as Los Angeles—which translates to tens of thousands of dollars or even more than $100,000 per unit. Thus, development projects should utilize market-rate wages instead.

- Streamline or eliminate CEQA: The California Environmental Quality Act and other unnecessarily burdensome environmental regulations, which add tens of thousands of dollars to the price of a home and suppress the supply of housing by imposing lengthy and expensive approval processes and litigation, which may hold up developments for many years or kill them altogether. Even worse, these laws and regulations are oftentimes used by labor unions or “not in my backyard” (NIMBY) groups to delay or destroy proposed housing developments for reasons that have nothing to do with the environment. Governor Newsom and the legislature tacitly acknowledged the unnecessary barriers imposed by CEQA when they exempted from CEQA’s environmental review process projects related to the purchase and rehabilitation of hotels, motels, vacant apartment buildings, and residential care facilities for the purpose of housing individuals experiencing homelessness. This privilege should be extended broadly to California property owners.

- Minimize development impact fees, which average about three and a half times the national average ($22,000 in California versus $6,000 nationally, although they can reach more than $146,000 in Irvine and nearly $157,000 in Fremont), and tailor them narrowly to the direct impacts of the developments to be built.