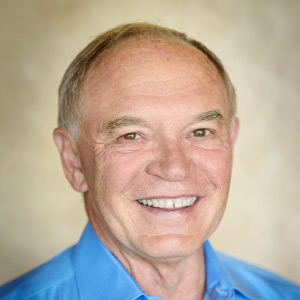

“Rick” Stroup was one of the founders of the environmental economics movement; he was a conservationist of the first rank. “Conserving” resources requires accounting for the opportunity costs of using those resources. But in the 1970s the focus of “environmentalism” was command and control; it fell to economists such as Richard L. Stroup, John A. Baden, Terry L. Anderson, and others to point out that prices embody and enforce a concern for opportunity cost better than any alternative system.

The essence of the environmental economics approach is the need to clarify and protect property rights. If the transaction costs of using tort law and negotiations are low enough, many of the problems of pollution and resource misuse are mitigated. In his book Cutting Green Tape: Toxic Pollutants, Environmental Regulation and the Law (Independent Institute, 2000, co-edited with Roger E. Meiners), Rick makes a powerful and incisive argument for claims that many traditional environmental activists found abhorrent: For one thing, you can be too careful, and that uses a lot of resources. Second, focusing liability on actors with deep pockets fails to reduce pollution, but wastes enormous resources on compliance and distorted incentives. Finally, far and away the greatest violators of environmental prudence and principles of conservation are state and (especially) federal government agencies. But the government immunizes itself from even the most basic accountability, while placing at risk the assets of companies and individuals who create value in the economy.

Rick was a native of Washington state, and was an environmentalist out of love for the outdoors and the natural world. But in studying economics (his B.A., M.A., and Ph.D. were all taken from the University of Washington’s outstanding economics department, which then included my own dissertation adviser and future Nobel Prize-winning economist, Douglass C. North), Rick came to see that the way to conserve resources was to give someone an incentive to make sure those resources are preserved and cared for into future generations. Government programs were either misdirected, or unintentionally converted valuable resources into a “commons,” with disastrous results. The key factor in policy, then, was not the stated intent, but the actual consequence. And market-based approaches consistently yield far better consequences than “expert”-driven command and control structures.

Stroup was one of the founders of the Property and Environment Research Center (PERC, 1980), and is recognized as one of the moving forces behind the intellectual movement now called the New Resource Economics. In addition to a prodigious output of scholarly books and articles, Rick published three very influential (and very different!) textbooks: Eco-Nomics: What Everyone Should Know About Economics and the Environment (Cato Institute, 2004); Economics: Private and Public Choice, with James D. Gwartney, now in its 17th edition (Dryden Press, and now Cengage); and Common Sense Economics: What Everyone Should Know about Wealth and Prosperity, with James D. Gwartney, Dwight R. Lee, Tawni Hunt Ferrarini, and Joseph P. Calhoun (most recently in 2016, St. Martin’s Press).

The editors of The Independent Review could think of no better way of honoring Richard Stroup than to include a personal letter, written just after his death, by one of Rick’s most prominent students. Terry Anderson, longtime President of PERC and De Nault Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution, allowed us to use this letter which he had sent to Rick’s spouse Jane Shaw, herself a prominent scholar, author, and advocate for free-market causes.

Speaking for myself, it was a blessing to have Rick in my adopted hometown of Raleigh, North Carolina for the final years of his life. Rick didn’t say much in crowds, but when he did speak it was worth hearing. We hope that readers can hear the echoes of that strong voice for free markets and effective conservation in Anderson’s letter, below.

Anderson explains: “I wrote this letter after receiving the news of Rick’s passing and only wish I had written it before. Rick was a mentor, friend, entrepreneur, scholar, writer, and one of the best economists I have had the privilege to know. I hope those who read it will reflect on all that Rick contributed to their lives.”

—Michael C. Munger, Duke University

18 November 2021

Dear Rick:

As usual, I am a day late and a dollar short. During this week you have come up in two conversations, one with my wife, Monica Guenther, and one with Don Leal, another of our many PERC colleagues. Of course, both were about the “good old days,” and good they were.

I told Don that without you, it is hard to guess where my career might have gone. For starters, it was you who got me through the “core exams.” After I failed the first round of the “micro core,” I hired you to be my tutor. Who could have been better than the one of the best micro-economists I have known. You would confront me with questions from previous exams (I think there was a list of 102 questions), hear or read my answer, and then critique them. I’m embarrassed to think now how bad I was! You didn’t just help me through the exam, you taught me to think like an economist.

When I went on the job market, it was you who notified me of the opening at Montana State. Given my performance when you were tutoring me, I wonder why. Perhaps you realized just how far I had come. I applied for the job, got the interview, and got the offer. The interview came after my visit to the University of Michigan, and I recall saying to several people that you and your colleagues asked me the best questions, all the time focusing on “the economic way of thinking.”

It was later that I learned that the offer would not have been forthcoming were it not for you. Apparently, when the faculty was debating whether to make me an offer, someone raised the question of whether I could teach advanced micro, given that my specialty was economic history. Whoever that was took it upon himself to call the University of Washington to see what the micro profs thought. Steve Cheung, from whom I had not taken a micro class, got the call and said I might be good at economic history, but not at micro. Again you rose to my defense, and again I assume you knew what you had taught me. You made another call to Gene Silberberg who confirmed your judgement, and the rest is history.

Even before PERC, you and PJ Hill sat in on a discussion seminar I taught using Cheung’s work on property rights. At that time, property rights economics was in its infancy. I don’t know what the students got out of it, but the three of us began to solidify the thinking that became the foundation of PERC.

You and I were among the first to attend Henry Manne’s “Law for Economists” programs. We spent three weeks on Key Biscayne being introduced to the “legal way of thinking.” Another cornerstone for PERC was being laid.

You and John Baden were the first to attend a Liberty Fund Conference. I think it was at UCLA and I know it included Armen Alchian, The stories and ideas you brought home became another stone in the foundation.

Then came PERC. You had known John when he was at MSU and were working with him on your Hutterite paper. When the two of you aired the idea of creating the Center for Political Economy and Natural Resources, I thought you were crazy. But with John’s entrepreneurship and your solid foundation for economic thinking, I joined the bandwagon, and my career changed yet again.

From that the two of you launched the Journalism Conference, without which Jane Shaw would never have come onto the scene. True confession—I thought she was pretty cute and clearly you did, too. Really, your relationship with her and ultimately your marriage that brought her into the PERC fold marked another turning point in my career. From you I learned to think like an economist, and from her, I learned to write like a journalist (well, not quite like she can write).

Writing this letter reminds me of many things that have slipped away. Few would believe that we grouse hunted together; that we snorkeled together in Florida; that we tasted wine together; and that we could recruit a group of economists to the department that gave it a reputation far beyond what it would have had without you.

Speaking of that reminds me of a recruiting dinner at which you were charged with ordering the wine, and deservedly so. When you tasted the wine, you told the waiter that it was no good and refused the bottle. He brought another, and you repeated the ritual and again refused the wine. I thought you were going a bit far, and suggested that it must have been good enough. Your response was for me to taste it myself. Of course, when it came to wine as with economic thinking, you were right.

As I told Don a couple of days ago, you made my career. Whatever talent I have as an economist started with you teaching me to think like an economist, a talent that few have—especially when compared to you. Thanks for all you did for me.