The overwhelming majority of “national founders” in the Western Hemisphere were violently driven from power or clung to power for lengthy periods. Only one of the handful who gave up power in an orderly fashion after a short period was a military leader – George Washington. This essay shows that our national founder and our national founding—free of entrenched power, assassinations, coups, exiles, and bloody power struggles—were exceptional.

Article

Heading home from a conference in the Bahamas a few years ago, I noticed a sign directing traffic to the Lynden Pindling International Airport. I asked the cab driver if he knew who Pindling was. Know him?! He knew all about him and had met him several times. Pindling was the “father of his country.” And the driver told me that Pindling was a great man. Eager to learn more, I asked him to explain. Pindling was the first Bahamian president, after the end of British rule. A man of the people, he did much to put power into their hands and improve the educational system, I learned. Then he let the “R” word slip out—a word he seemed to want to unsay—in describing Pindling’s “regime.” I decided to learn more when I returned home.

As biographer Michael Craton (2002) explains, the Right Excellent Sir Lynden Pindling served as prime minister from 1973 to 1992. At his death in 2000, Anglican Archbishop Drexel Gomez eulogized him as a pioneer who “united the people and set the nation on its path out of Egypt.” Others spoke of his “gift of being able to walk and talk with monarchs and ordinary people” and called him “a man of the people; a man of peace” (411). Craton notes that Pindling “hugely expanded” educational facilities, which became “available equally to all.” “For the less fortunate in society medical and other social services became much more plentiful and more freely available” (418). “Most of all, however ... what Lynden Pindling did was to destroy for all time what he himself called the Black Crab mentality” in which West Indian islanders “tended to be pettily jealous of any among them who showed ambition or ability to scramble out of the common barrel, and pulled them back down again if they could” (421).

However, as Craton explains, “Pindling and his associates ... became wealthy, or wealthier, while in office.... Undoubtedly he did receive substantial gifts from time to time, ‘sweetheart’ loans, and generous payment for nominal services such as ‘finder’s fees’” (414–15). “Pindling was said to be especially careless about the notoriety of ... some of the company that he kept. He met, was even on amicable terms with, fugitives wanted in their own countries (and the United States) for drug-running, money laundering, and other financial” crimes (416). Charges of corruption began early in Pindling’s career, especially payments from mob-backed casino interests. In 1983, a report entitled The Bahamas: A Nation for Sale by investigative journalist Brian Ross aired on NBC TV, which claimed that Pindling and his government accepted bribes from Colombian drug smugglers, particularly Carlos Lehder, cofounder of the Medellín Cartel, in exchange for allowing them to use the Bahamas as a transshipment point to bring cocaine into the United States. Public outcry led to the creation of a commission of enquiry in the Bahamas. The commission found that from 1977 to 1984, Pindling spent eight times his reported earnings and that Pindling and his wife received $57.3 million in cash (Nathan 2013, 61).

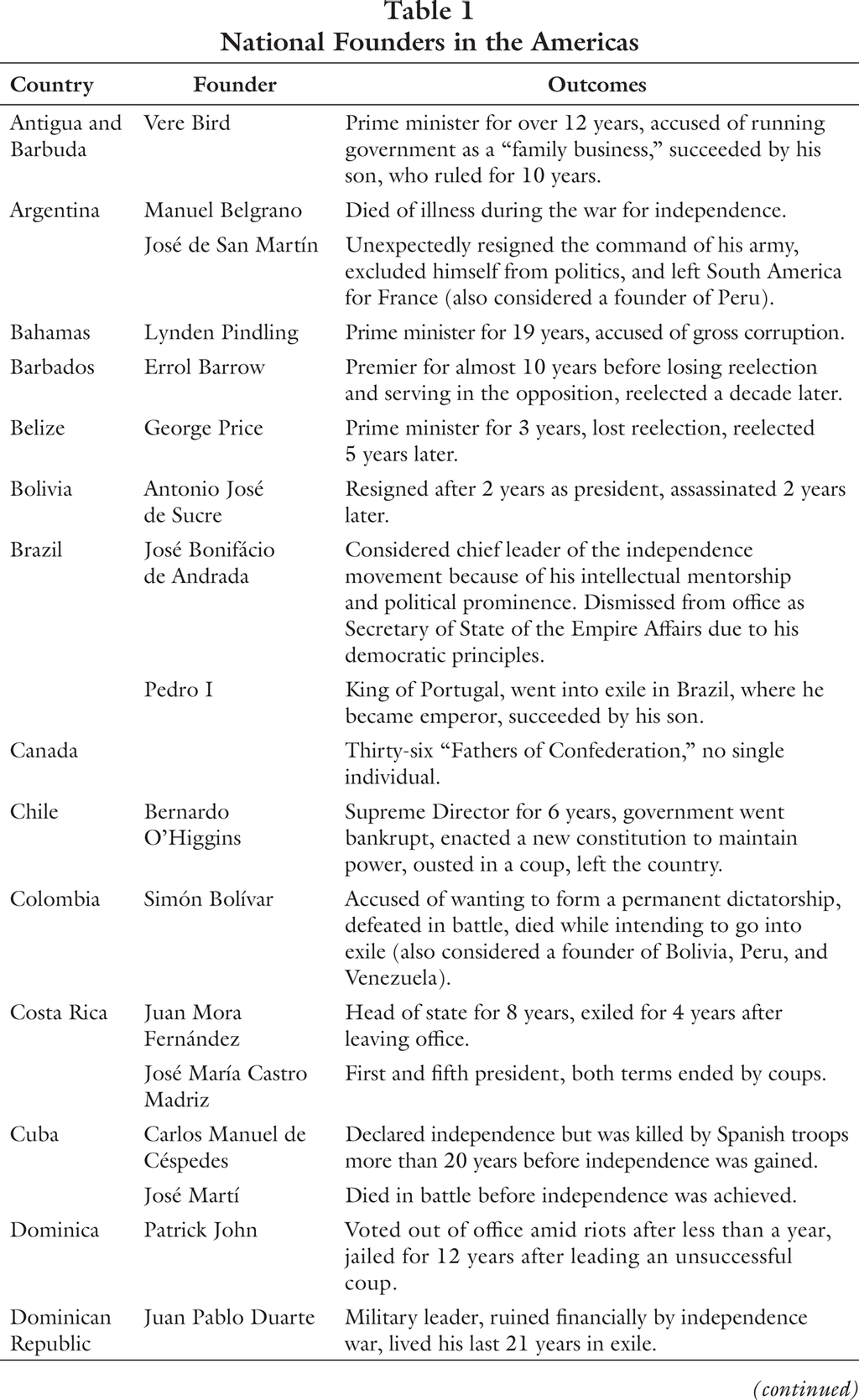

It may be instructive to compare Pindling to other men from the Western Hemisphere who were known as national founders or “the fathers of their country.” Table 1 summarizes the outcomes of thirty-four “national founders” from two dozen countries in the Americas, all of which achieved independence after breaking away from European powers.[1] As the table suggests, it’s not generally a pretty picture.

Like Pindling in the Bahamas, many of these national founders clung to power, including José Rodríguez de Francia, who was dictator in Paraguay for over a quarter century; Eric Williams of Trinidad and Tobago, whose term as prime minister equaled Pindling’s at nineteen years; Vere Bird of Antigua and Barbuda who ruled for twelve years, was accused of running government as a “family business,” and was succeeded by his son, who ruled for ten years; Patrick John of Dominica, who tried to regain office through a coup; and José Antonio Páez of Venezuela who held the office of president for eleven years but was the “power behind puppet presidents” for three decades. He is “considered a prime example of a nineteenth-century South American caudillo, and imbued the country with a legacy of authoritarian rule that lasted, with few exceptions, until 1958” (Wikipedia, s.v. Páez, n.d.).

Even more of them were violently driven from power—toppled by a coup or sent into exile, including Bernardo O’Higgins, Simón Bolívar, Juan Mora Fernández, José María Castro Madriz (who was ousted twice by coup), Juan Pablo Duarte, Matías Ramón Mella, Eric Gairy, Francisco Morazán, and Johan Ferrier. Worse yet, several of them died violent deaths, sometimes during the struggle for national independence, but sometimes afterward. Antonio José de Sucre of Bolivia was assassinated, as was Jean-Jacques Dessalines of Haiti. José Rodríguez de Francia of Paraguay took extreme precautions to avoid assassination. Apparently, he would “lock the palace doors himself, unroll the cigars that his sister made to ensure there was no poison ... and sleep with a pistol under his pillow.... No one could come within six paces of him or even bear a cane near him” (Wikipedia, s.v. Rodríguez de Francis, n.d.). Francisco del Rosario Sánchez of the Dominican Republic was executed after leading an uprising.

In only a handful of cases did national founders give up power in an orderly fashion. Lynden Pindling conceded defeat after almost two decades in power. The clearer cut cases are Errol Barrow in Barbados, George Price in Belize, Norman Manley and Alexander Bustamante in Jamaica, and George Washington. Only one of these—Washington—was a military leader in a country that fought a war of independence who then voluntarily relinquished power. Washington gave up power not once, but twice: first when he handed over his military power at the end of the American Revolution and again when he refused to seek a third term as president. This makes the founding of the United States strikingly unique.

Wilfred McClay (2019, 53), after outlining the British strengths in the Revolutionary War, explains that “the Americans enjoyed certain very real advantages.... First, there was the fact that they were playing defense.... The Americans also had a second advantage. They were blessed with an exceptional leader in the person of George Washington.”

Hearing that Washington would step down from the presidency and return to Mount Vernon, King George III told painter Benjamin West that “that act closing and finishing what had gone before and viewed in connection with it, placed him [Washington] in a light the most distinguished of any man living, and that he [George III] thought him [Washington] the greatest character of the age.”2

“Washington, having just risked his life for his countrymen, has won the battle and become indisputably the most popular man in America. The people don’t really know what comes next, but they want leadership—and they would surely have made him king had he wanted the position. But instead, he comes to a meeting of the Continental Congress—which represents the rule of the common man, rather than the rule of the rich or well-born—and he relinquishes control of the army. He lays down power. He could have been an American Julius Caesar holding sway over a new North American empire. But he refuses. He doesn’t seek power over his neighbors; instead, he seeks to teach them that they should look for their happiness and fulfillment in their families and in their communities, not in the halls of power or in the ranks of military might.... Each of our lives has been shaped by this noble act” concludes Ben Sasse (2018, 143).

When Lynden Pindling conceded defeat after nearly two decades in power, he said, “The people of this great little democracy have spoken in a most dignified and eloquent manner (and) the voice of the people, is the voice of God” (370). George Washington understood that the voice of the people is not the voice of God, that the voice of the people is merely the voice of the people and shouldn’t be a fig leaf behind which those hungering for power hide or even a means to save face after a life of corruption. The “father” of our country, set higher goals for himself and for the nation. I am thankful that there was no Washington “regime,” that General Washington quashed the Conway Cabal among some of the Continental Army’s officers to challenge civil authority, that citizen George Washington took a leading role in reforming the Articles of Confederation and framing our exceptional and enduring U.S. Constitution, and that President George Washington walked away from power after two terms. That was just enough time to establish many precedents for the nation, give dignity to the highest office, and recognize that ours is a system of checks and balances—just enough time to set it on the road to peace and prosperity (Chernow 2010; Lengel 2016).

This national founder and this national founding—free of entrenched power, assassinations, coups, exiles, and bloody power struggles—were unprecedented. His example and that of his fellow citizens remade world history. As people constantly try to rewrite and reinterpret history, we cannot forget our good fortune in this founding (Irwin and Sylla 2011).

Note

[1] The list comes from Wikipedia, s.v. “List of National Founders.” I have omitted these founders on Wikipedia’s list: Pedro Cabral, the explorer who discovered Brazil in 1500; Diego Portales, who “is sometimes considered” a founder of Chile “due to his influence in the 1833 Constitution” and who did not become a head of state; Francisco de Paula Santander, who wrote the first constitution of Colombia; Antonio Nariño (“Precursor of the Independence”) and Camilo Torres, “who were the most relevant statesmen of the First Republic” of Colombia—as Simón Bolívar clearly has precedence over them; Juan Rafael Mora Porras, president during Costa Rica’s campaign against filibusterer William Walker about three decades after independence; Fidel Castro, who led Cuba after it had been independent for more than half a century; Henri Christophe and Alexandre Pétion, who “were also important figures of early Haiti”; twelve men who “according to the decrees of the Congress of the Union of Mexico issued in 1822 and 1823” were the Mexican founders, all of whom are listed after Miguel Hidalgo, who is nearly universally considered the “father of Mexico”; Pachacuti, the ninth Sapa Inca of the Kingdom of Cusco, the founder of the Inca Empire; six “key founders” in the United States—John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison; and Rómulo Betancourt, “the founding father of modern democratic Venezuela,” and Hugo Chávez as “the founding father of modern totalitarian Venezuela.”

References

Chernow, Ron. 2010. Washington: A Life. New York: Penguin.

Craton, Michael. 2002. Pindling: The Life and Times of Lynden Oscar Pindling, First Prime Minister of The Bahamas, 1930–2000. Oxford: Macmillan Caribbean.

Lengel, Edward G. 2016. First Entrepreneur: How George Washington Built His—and the Nation’s—Prosperity. Boston: Da Capo Press.

Irwin, Douglas A., and Richard Sylla. 2011. Founding Choices: American Economic Policy in the 1790s. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

King, Charles, ed. 1896. The Life and Correspondence of Rufus King, Volume III. New York: G. P. Putnam.

McClay, Wilfrid. 2019. Land of Hope: An Invitation to the Great American Story. New York: Encounter Books.

Nathan, Samuel. 2013. Caribbean-opedia. N.p.: Lulu.

Sasse, Ben. 2018. Them: Why We Hate Each Other and How to Heal. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Wikipedia. n.d. José Antonio Páez.

Wikipedia. n.d. José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia.

Wikipedia. n.d. List of National Founders, Americas.

| Other Independent Review articles by Robert M. Whaples | ||

| Summer 2024 | The Journey of Humanity: The Origins of Wealth and Inequality | |

| Summer 2024 | Of Boys and Men: Why the Modern Male Is Struggling, Why It Matters, and What to Do About It | |

| Summer 2024 | These United States: Our Nation’s Geography, History and People | |

| [View All (96)] | ||