Overview

California has become the national poster child for high housing costs and homelessness. Although no single lawmaker or regulator is to blame for California’s housing crisis, a complex array of regulatory obstacles enacted by politicians at various levels of government and pushed by special interests over decades have made California ill-equipped to accommodate the state’s growth. The effect has been a supply of housing that does not keep up with demand, resulting in skyrocketing housing costs, strained budgets, homelessness, and an outflow of people from the Golden State.

It is for these reasons that the Independent Institute has given the ninth California Golden Fleece® Award to California state and local politicians, government planners, regulators, and activists for inept housing policies. The award is given quarterly to California state or local agencies or government projects that swindle taxpayers or break the public trust.

This Golden Fleece report dares to state an unavoidable truth: housing prices and accessibility are determined by the interaction of supply and demand, and government regulations have constrained the supply side of the equation, exacerbating California’s housing and homelessness crises. Bureaucratic red tape impacts every stage of the development process, and there is no shortage of actors trying to maintain the status quo because they benefit from it financially or in other ways. Despite much hand-wringing and pronouncements by politicians to “fix the problem,” state and local governments have made the problem worse, especially for lower-income residents.

In July 2019, San Francisco Mayor London Breed asked, “Why does it take so damn long to get housing built?” This Golden Fleece report answers her question, and many more, and offers much-needed solutions. Fixing the problem requires a multipronged approach.

California legislators must ease state regulations that impose huge costs on housing construction, stop or delay projects, and disincentivize more rental properties. Local officials need to liberalize zoning and other building regulations, especially in high-demand areas, that prevent much-needed construction of new housing or that prevent the conversion of old buildings into residential housing. Entrepreneurs should be encouraged to enter housing markets across the state to provide creative and low-cost solutions to meet consumer demands for housing, thereby eliminating the government-created shortage.

Housing is a fundamental part of life. The link between consumers and housing entrepreneurs has been severed by government policies, and this link must be reestablished to restore civil society for all Californians. The need for fast and affordable housing construction is especially critical today because of California’s horrific wildfires of 2017 and 2018, which destroyed tens of thousands of homes, businesses, and schools across the state.

The High Cost of Housing in the Golden State

California is the world’s fifth largest economy, recently surpassing the United Kingdom in annual gross domestic product. Unemployment in the state is at a record low rate of 4 percent. By these measures of economic health, California is doing well. Yet housing statistics provide a contrasting story about the quality of life in the Golden State.

Between the late 1980s and 2006, California home-ownership rates steadily trended upward. But during most of the past decade, home-ownership rates have declined in the state. The most recent data from the US Census Bureau estimates that 56 percent of California households own the residence they live in, which is down from 60.2 percent in 2006, and well below the current national average of 64.1 percent. Only New York and Washington, DC, have lower rates of home ownership. California’s low home-ownership rate is partially driven by the high cost of housing.

In 2015, California’s nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO) issued a report on the state’s high housing costs, in which it discussed several underlying causes. The agency reported that California’s home prices were about 30 percent higher than the national average in 1970 and rose to 80 percent above national levels by 1980. Today, its home prices are 250 percent above the national average, while average monthly housing rents are about 50 percent above the national average.

According to the most recent data available from the California Department of Finance, the median price for a home in the Golden State was $611,420 in June 2019, a new record price. Housing prices hit record highs despite a “weak” California housing market—home sales statewide were down nearly 6 percent in the first half of 2019 compared to the year earlier. Transactions monitored by online real estate database Zillow show that, over the past 10 years, median home sale prices in California have increased by 72 percent, from $291,000, adjusted for inflation, to about $501,000. They estimate that the median home listing price is currently $549,000. And the median monthly rent has increased, too.

The median monthly rent paid for a one-bedroom apartment was $1,679, adjusted for inflation, in November 2010. Currently, median rent paid for a one-bedroom unit is $1,906. But rent is much higher in certain locations. According to apartment rental platform Zumper, the median monthly rent for a one-bedroom apartment in San Francisco is $3,720, a record high and the highest rent in the nation.

Meanwhile, the average household income in California has not kept pace. In 2009, the median California household income was $70,300 per year in 2019 dollars. By 2017, the most recent year for which data are available, median household annual income only increased about 6.5 percent, to $75,000 (adjusted), while home prices increased 72 percent. A third of California renters and 16 percent of homeowners spend more than half their income on housing.

In the nine-county San Francisco Bay Area, a typical home buyer pays nearly nine times the area’s median annual household income to purchase a home, according to a study by Clever Real Estate. In 1960, a home buyer paid about twice the median annual income for a home. The recommended price-to-income ratio is 2.6. Eight of the 10 least-affordable cities nationwide, as measured by the price-to-income ratio, are in California.

Only 30 percent of households in the state can afford a median-priced home in the county in which they live, according to the California Association of Realtors. The national average is 54 percent. Elliot Eisenberg, partner economist at MLS Listings, sums up California’s housing market, “This is truly a housing market that’s a complete wreck.”

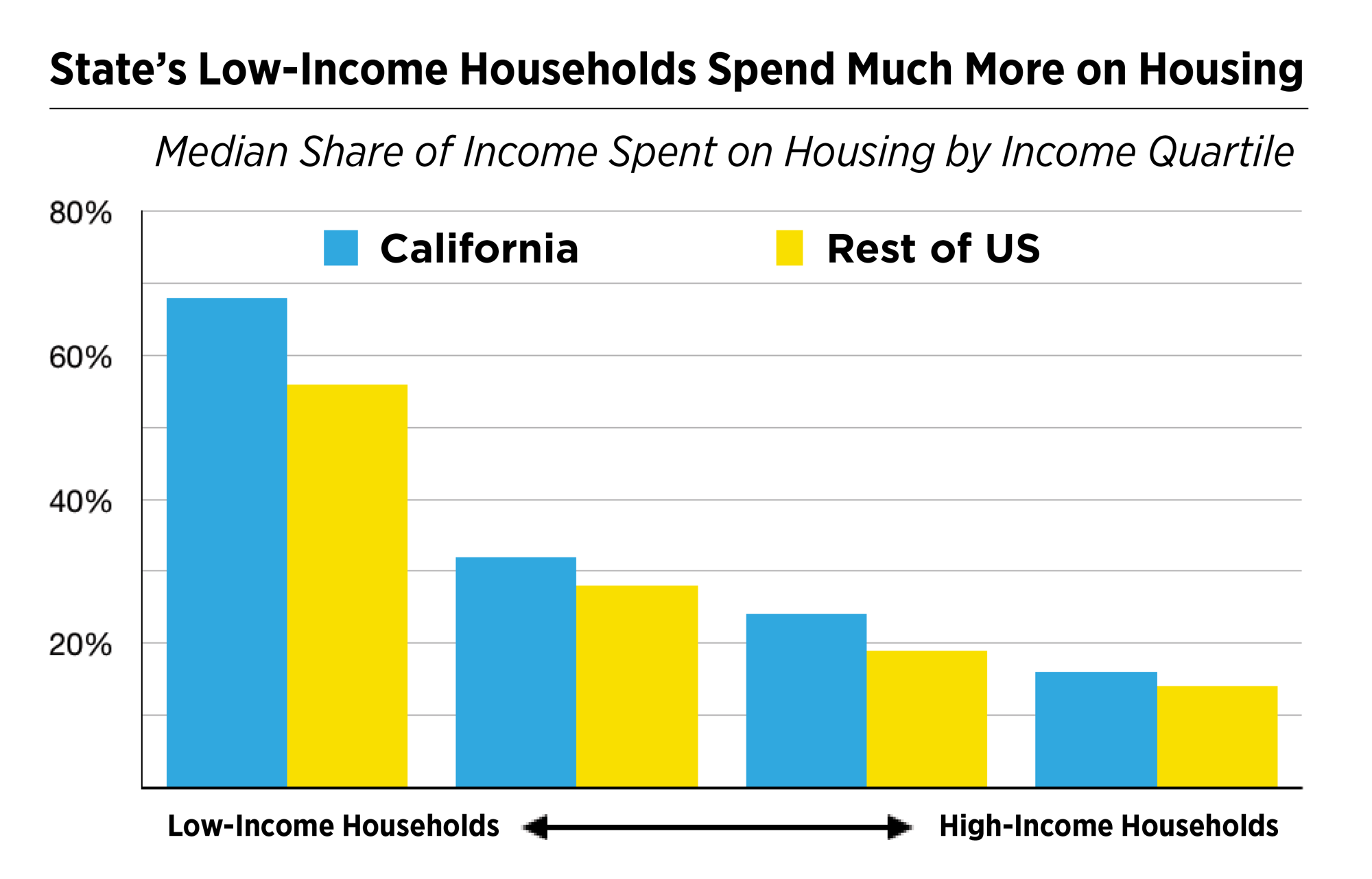

California’s high housing costs are especially burdensome for low-income households. As the figure above, prepared by the LAO, illustrates, “California households with incomes in the bottom quartile [i.e., 25 percent] report spending 67 percent of their income on housing, about 11 percent more than low-income households elsewhere. This ‘gap’ persists across most income groups, but becomes smaller as income increases.” In addition, people in California are more likely to live in crowded housing conditions than people living in other states.

Many people have responded to the high housing costs by leaving California. The US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey has shown a consistently negative net domestic migration for California during the past several years: more people left California for other states than came to California from other states. On net, from 2007 to 2018, California lost nearly 1.3 million residents to domestic migration (see here and here). And since 2016, overall net migration (including international migration) has been negative in California.

The outward-migration has been concentrated among lower-income and middle-class residents and the less educated, who are increasingly stretched thin in California. Testimonials and patterns of movement reveal a lack of affordable housing to be a driving factor among people increasingly looking elsewhere to achieve the American dream. The exodus is likely to continue. A July 2019 Quinnipiac University poll found that 45 percent of Californians believe they cannot afford to live in the Golden State, and nearly 80 percent of Californians think the state has a housing crisis. In August 2019, California Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) bluntly acknowledged, “The California dream is in real peril if we don’t address the housing crisis.”

Sky-High Housing Prices in California Cities and the Human Tragedy of Homelessness

California’s largest metropolitan areas best illustrate the dysfunction in the state’s housing markets. They also highlight how state and local officials have failed to provide real solutions to the problem.

The prosperity of America’s technology sector has dramatically transformed the San Francisco Bay Area, bringing scores of new jobs and workers to fill those jobs. But coalitions of San Franciscans and members of many other Bay Area communities have ferociously fought the construction of new housing to meet the demands brought about by the tech boom. In 2018, San Francisco netted only 2,579 new housing units, a 42 percent decrease from 2017 and the lowest gain in five years. The result is increasingly unattainable housing prices and unaffordable rents, contributing to a growing homelessness problem plaguing the Bay Area.

According to California Employment and Development Department statistics compiled by University of California, Berkeley, economist Enrico Moretti, San Francisco County added about 38,000 new jobs between 2016 and the end of 2018. But over that time period, only 4,500 new housing units were permitted. As he notes, the resulting surge in housing prices has been profitable to existing homeowners, who benefit from a shortage, but renters have suffered mightily. According to research company CoreLogic, the median price paid for a new or existing home or condo in the Bay Area was $810,000 in August 2019. Bay Area communities have experienced surges in rental prices in recent years with some communities experiencing double-digit percentage increases in rental prices in just one year.

Extreme housing costs have also hit Los Angeles County, where the median home price now hovers above $600,000, and about half of all renters report spending more than 30 percent of their income on housing. With rents on a one-bedroom apartment averaging $2,500 per month on the low end, and as much as $3,500 per month in places like Santa Monica, a renter would need to earn more than three times the minimum wage to cover housing costs, according to estimates from the California Housing Partnership. So it is unsurprising that halfway through 2018 Los Angeles County had a net 13,000 fewer residents than it had a year earlier.

Adding new housing in Los Angeles is extraordinarily difficult due to zoning laws that explicitly prevent certain types of much-needed housing. The city currently bans anything other than detached single-family homes on about 75 percent of its residential land. As the New York Times notes, “In 1960, Los Angeles had the zoned capacity for about 10 million people.... By 1990, Los Angeles had downzoned to a capacity of about 3.9 million, a number that is only slightly higher today.”

Efforts to “upzone,” or to rezone certain areas to allow construction of denser multifamily housing, have until now been defeated in the California legislature. These efforts include Senate Bill (SB) 827 and SB 50. In their place, one Los Angeles area state senator who opposed the upzoning bills instead introduced a bill favoring another approach: a special license plate designed to bring awareness to the housing crisis. Money raised through the sale of the “California Housing Crisis Awareness” license plates would go into an existing program that helps moderate-income people purchase homes. This “solution” would be laughable if the problem were not so serious.

A recent poll by the University of California, Berkeley, of registered California voters found that 86 percent in Los Angeles County and 92 percent in the Bay Area consider affordable housing either a “somewhat serious” or “extremely serious” issue in their area. Statewide, 56 percent of voters, including majorities in both metropolitan areas, said they have considered moving due to rising housing costs. Of course, for those who are unable or unwilling to move, being priced out of their homes and apartments, or regulated out of their residences, makes homelessness a real possibility.

The human tragedy of homelessness

In Los Angeles and San Francisco, and many other cities across the state, increases in the number of homeless have made the affordable housing deficit an unavoidable “doorstep” problem. The prevalence of people sleeping on sidewalks and in tent cities serves as a constant reminder of the failures to effectively tackle the problem. Recently, a staggering 82 percent of Californians believe that homelessness is a “very serious” problem in the Golden State, and 67 percent said that “California” is doing “too little” to help the homeless. For the first time in its 20-year history, the September 2019 survey of Californians by the Public Policy Institute of California found homelessness to be the top concern (tied with jobs and the economy). A full 15 percent of Californians said homelessness is the state’s “most important issue.”

According to the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), there were 151,278 people homeless in California as of January 2019, or about 27 percent of the nation’s homeless population. In 2010, California had an estimated 123,480 homeless people, so total homelessness has trended upward during the past decade. A 2018 homeless survey found that California alone accounts for about half of all chronically unsheltered homeless people in the United States—people living on sidewalks or in parks or cars—a level about four times more than California’s share of the US population. It is important to be mindful that a point-in-time count likely underestimates the number of homeless people during a calendar year by two to three times, as people cycle in and out of homelessness throughout the year.

Homelessness is a multifaceted condition. Many of those living on the streets suffer from drug addictions and mental illnesses that require individualized attention and care. According to data from HUD, and as reported by Victoria Cabales of CalMatters, in 2017, 26 percent of California’s total homeless population suffered from mental illness, 18 percent struggled with substance abuse, and 24 percent self-identified as victims of domestic violence.

In San Francisco, 42 percent of its homeless population self-report alcohol and drug use as a “health condition that may affect [their] housing stability or employment,” while 39 percent report psychiatric and emotional conditions, and 37 percent self-report post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Also, 89 percent of the city’s homeless are currently unemployed. In many cases, therefore, housing must be paired with wraparound support services in order to permanently transition people out of homelessness.

Homelessness is exacerbated when those capable of getting back on their feet have nowhere plausible to go. Other people are on the brink of homelessness. A rent increase or eviction could put them on the streets because, again, there is nowhere plausible to go. The housing stock for very low-income people has been decimated from decades of restrictions impacting what once was called rooming houses, boarding houses, and single room occupancies (SROs). The Council of Economic Advisers in Washington, DC, estimates that homelessness would decline by 54 percent in San Francisco and by 40 percent in Los Angeles if their “housing markets were deregulated,” allowing housing prices to fall. Nearly 60 percent of Californians surveyed have said that the cost of housing is a “major cause” of homelessness.

Los Angeles County has experienced a 12 percent increase in homelessness in just the past year alone, totaling nearly 59,000 people. And the city of Los Angeles has experienced a 16 percent increase during the same period, surging to about 36,000 people, as homeless encampments in downtown Los Angeles expand despite new government initiatives. Los Angeles alone has nearly 20 percent of the nation’s unsheltered homeless population. The Atlantic reported in March 2019 that typhus, a medieval disease, and tuberculosis are spreading through homeless camps and shelters in Los Angeles.

Meanwhile, San Francisco experienced a 17 percent increase in its homeless population during the past two years, using the federal government’s homeless definition, or an astonishing 30 percent increase in homelessness, using the city’s own broader definition of homeless. Regardless of the definition used, homelessness has spiked in San Francisco. The city’s unsheltered homeless population jumped from 4,353 in 2017 to 5,180 in 2019. San Francisco’s rampant street misery has been well documented. Similarly, Sacramento’s homeless population increased almost 20 percent during the past two years.

In response to the homeless crisis, Assembly Bill (AB) 1487 was enacted in the 2019 California legislative session, which is intended to increase government financing of Bay Area affordable housing units through new taxes and bonds. In addition, Governor Newsom signed the fiscal year 2019–2020 state budget that authorizes a historic $1 billion in new aid to California cities to fight homelessness, including $650 million in emergency sheltering and $120 million for programs that coordinate housing. But similar aid provided in 2018 by then–Gov. Jerry Brown (D) did not prevent the surge in homelessness.

Also, on July 16, 2019, Newsom created a task force of thirteen “regional leaders and statewide experts”—primarily politicians—to advise his administration on how best to spend the $1 billion to “combat homelessness” in the new state budget.

Today, California governments at all levels are fixated on generating more “affordable” housing. But this fixation can produce bizarre, counterproductive results. For example, a San Francisco developer, Reliant Group, recently bought apartment properties in the East Bay and North Bay using government subsidies, then it evicted nearly 900 established tenants (many of them elderly), converted the existing apartments into affordable housing units, then rented the units to low-income tenants, while pocketing tax credits through the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit programs and pocketing state housing revenue bond money. Before eviction, the established tenants occupied a mix of market-rate, rent-controlled, and affordable units—hardly a wealthy group of people. It is important to be leery of government claims, therefore, that its programs are producing more affordable housing—it may simply be displacing one group of people for another group of people without adding to the housing stock, which is the only permanent solution to the housing shortage.

In addition to federal and state programs, many local governments across the state have developed elaborate housing plans, often with specific housing goals, but these are seldom met because of government delays, inefficiency, and burdensome overregulation. Perhaps the most elaborate plan is Plan Bay Area, which covers the San Francisco Bay Area. The Association of Bay Area Governments (ABAG) and the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC) adopted Plan Bay Area in 2013, a master plan for housing, transportation, and land use in the nine-county Bay Area through 2040.

Plan Bay Area creates “Priority Development Areas” (PDAs) throughout the 9 counties and 101 cities that are members of ABAG. A full 80 percent of the new housing built in the Bay Area through 2040, as its population grows from 7 million to 9 million, will occur in the PDAs. All of Plan Bay Area’s development areas are confined to less than 5 percent of the land and clustered near mass transit such as BART, Caltrain, and the Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority (VTA). Roughly 75 percent of the land in the Bay Area is already off-limits to development, but the plan will jam more people into a smaller area by further restricting land use through “Priority Conservation Areas” and favoring “stack-and-pack” housing.

Plan Bay Area disproportionately harms the region’s low-income and minority populations by targeting their neighborhoods for future housing development. Entrepreneur-led gentrification driven by changing consumer demands is one thing, but in the Bay Area, gentrification is often the result of government programs deliberately targeting the neighborhoods of people who are less politically connected—a shameful practice. And densification in the Bay Area is driven overwhelmingly by artificial government land-use restrictions, rather than the housing choices of consumers.

Perhaps the worst example of government programs targeting the neighborhoods of minority and low-income people in the Bay Area was the demolition of the Fillmore District in San Francisco beginning in the 1950s. This federal, state, and local government “urban renewal” project—often called “urban removal” by its critics—used force to “relocate” African-Americans from their homes and demolish their once-thriving neighborhood (see Western Addition A-1 and Western Addition A-2). Some critics of the Fillmore demolition called it “Negro removal” or “Black removal.” Walter Thompson wrote an excellent historical series on the disgraceful Fillmore project: “How Urban Renewal Destroyed the Fillmore in Order to Save It” and “How Urban Renewal Tried to Rebuild the Fillmore.” Thompson concluded, “The number of African-Americans displaced from the Western Addition as a result of urban renewal is unknown, but estimates start at 10,000 people. Less quantifiable is the cultural aftermath; a once-thriving district studded with minority-owned businesses, nightclubs, and hotels in the heart of San Francisco now exists mostly in faded photos and oral histories.” Unfortunately, Plan Bay Area resurrects the ghosts of the Fillmore tragedy.

In Southern California, Los Angeles voters approved a $1.2 billion bond measure, Proposition HHH, in 2016 and a sales tax increase, Measure H, in 2017 to build 1,000 new housing units each year over the next decade. But the typical delays and setbacks emblematic of government projects quickly emerged, with project delays averaging 203 days each. As of July 2019, none of the new housing units were completed yet, and only 239 were projected to be completed in 2019, if all went according to plan. University of California, Los Angeles, law professor emeritus Gary Blasi described the situation, “This is ordinary government, but it’s an extraordinary problem.”

In San Francisco, where homelessness has reached record levels, Mayor London Breed led the fight for passage of a $600 million affordable housing bond measure—the largest housing bond in city history—which could potentially fund 2,800 units. Voters approved the bond measure, Proposition A, in November 2019. City officials have also advanced plans to build new housing to shelter a portion of its homeless population. But once again opposition from local groups has delayed or blocked new construction plans through expensive litigation. In response, Breed noted, “Our city is in the midst of a homelessness crisis, and we can’t keep delaying projects like this one that will help fix the problem.”

Government-created roadblocks

The delay or blocking of much-needed housing is a problem that the entire state has failed to confront for decades. Groups—primarily current homeowners and established residents—that oppose the construction of new homeless shelters and other housing often invoke the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), claiming insufficient review of a project’s environmental impacts. CEQA has been used to slow or stop housing development in the Golden State since it was signed into law in 1970.

CEQA requires state and local governments to analyze and publish the impacts of development projects on the environment and mitigate impacts if necessary. The law was intended to protect California’s natural environment from harm, but its scope has greatly expanded to include a project’s impacts on line-of-sight views and traffic patterns, among other things. CEQA requires local governments to hear CEQA-based appeals against projects, and these are often grounds for challenges in court that can drag on for years.

“Without CEQA approvals, no new housing can be built in California, so it’s very integral to everything we do,” said Katia Kamangar, executive vice president and managing director of SummerHill Housing Group. “While well intentioned, unfortunately, in nearly all of the cases we’ve been involved in, CEQA was used as a vehicle for stalling a project already approved by the local jurisdiction,” Kamangar said. Even just one person can delay or stop a project through court action. “We see these situations largely as a loss for the region and one of the reasons why delivering new housing in California takes years and why housing costs are significantly higher here than in other parts of the country,” Kamangar concluded.

Timothy Coyle, a former director of the California Department of Housing and Community Development, has seen CEQA’s implementation from the inside and concludes that it is “the mother of all government-sponsored obstacles to development.” Business rivals, environmental activists, and neighborhood groups use CEQA to delay, and whenever possible, stop development projects. Unfortunately, CEQA and other regulations that are discussed below prevent an effective response by entrepreneurs to the housing shortage.

Clearly, despite multiple attempts over many decades at the federal, state, and local levels, the housing and homelessness issue has not been “solved” by governments; in fact, it has become worse. Rather than arguing over which government program would best alleviate the suffering, a better question to ask is why have solutions led by housing entrepreneurs not emerged. Housing is a fundamental part of life that was provided by entrepreneurs at every price point for centuries. But today government policy prevents housing entrepreneurs from satisfying the housing demands of Californians. This Golden Fleece report provides solutions for reestablishing the critical link between consumers and housing entrepreneurs, which would help to restore civil society for all Californians.

The Urgent Need to Rebuild After California’s Horrific Wildfires

Fixing California’s housing crisis became more urgent in the aftermath of the record wildfires of 2017 and 2018. In 2017, nearly 9,000 wildfires ravaged California, burning 1.2 million acres of land, destroying more than 10,800 structures, and killing at least 46 people.

The 2018 wildfires were even more destructive. More than 1.8 million acres of California land burned. People lost 17,133 residential structures, 703 commercial/mixed residential structures, and 5,811 minor structures. That year was also California’s deadliest year for wildfires, with more than 100 people killed, including 86 fatalities from the Camp Fire in and around the town of Paradise in Butte County. Scott McLean, spokesman for the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CAL FIRE), called the 2018 wildfire season “the worst in recorded history.” The Mendocino Complex Fire in July 2018 was the largest fire in California recorded history, and the Camp Fire in November 2018 was the deadliest fire in California recorded history.

The wildfires of 2018 were devastating for many communities, but the Camp Fire was catastrophic for the small town of Paradise. In the aftermath of what would be recognized as the deadliest wildfire in state history, surviving residents of Paradise were left to rebuild their homes and businesses from scratch, while neighboring communities experienced a sudden surge of people desperately seeking refuge and housing. What they all rapidly discovered were the consequences of a deeper web of problems: the overregulation of housing construction stands in the way of a return to normalcy.

When the Camp Fire began in early November 2018, California was already well into fire season. A combination of high temperatures and strong winds, an abundance of dead and overgrown vegetation, and chronically misguided CAL FIRE policies that disproportionately prioritize fire suppression over fire prevention provided the perfect storm for megafires. Indeed, fire season took off quickly. By early August, dozens of fires throughout the state had already set records, burning about a million acres, forcing mass evacuations, and taking a handful of lives. The Trump administration declared the wildfires a federal disaster. But, as then–CAL FIRE Chief Ken Pimlott ominously warned the public at the time, “Fire season is really just beginning.”

The warning proved to be an understatement of what was to come. On the morning of November 8, 2018, a Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E) Rock Creek Powerhouse worker reported a wildfire near Poe Dam, on the railroad tracks under a power transmission line. Within minutes, a torrent of other calls came in to 911, including from the Paradise Police Department. High winds spread the fire quickly; within an hour, the Butte County Sheriff’s Department broadcast an evacuation order for the town of Pulga, and shortly thereafter an order was placed to begin evacuating residents of Paradise.

Residents scrambled to leave their homes, but many did not make it out alive. The Camp Fire took 86 lives—disproportionately elderly residents of Paradise—and destroyed nearly 19,000 structures including almost 14,000 residences. All told, the fire burned more than 150,000 acres, an area larger than the city of Chicago. Investigators would later determine that PG&E was at fault for the Camp Fire, blaming power lines for sparking the initial fire.

Approximately 90 percent of residences in Paradise were destroyed by the Camp Fire, sending nearly 20,000 people to relocate to the relatively small college town of Chico. Similar to other California cities, Chico had been experiencing a worsening housing shortage and rising prices before the Camp Fire. When the Paradise evacuees arrived, Chico was ill-equipped to handle the inflow of people. The day before the destructive wildfire erupted, the city’s housing vacancy rate was 1 percent. Overnight, every hotel and guest room was occupied. And hundreds of people were living out of their cars, RVs, or in Red Cross emergency shelters throughout the city. Meanwhile, children displaced by the fire attended school in makeshift classrooms in a local hardware store.

More than six months after the Camp Fire erupted, the situation had not significantly improved. The rebuilding of Paradise remains slow. Residents have been warned by Planning Committee officials that rebuilding their town will be a prolonged process. But the effects of delay are significant. Many displaced residents have tried to move forward by rebuilding their homes, businesses, and lives by complying with official procedures, only to be slowed by an ever-changing landscape of regulations and paperwork. When officials learned that debris cleanup could harm local frog species, they halted work on about 800 sites, awaiting environmental clarifications from state and federal agencies. This “absurd” reason for delay, as State Sen. Jim Nielsen (R−Chico) described it, agitated landowners—many of whom have already received rebuild permits—and introduced new costs and uncertainty to the rebuilding process.

Meanwhile, Chico residents continue to suffer from a dysfunctional housing market and the problems caused by a mismatch between demand and supply. Nerves are frayed in Chico, crime and motor vehicle crashes are up, hospitals are overcrowded, and long-standing political divisions have exploded. The growth in demand for housing far outpaces any increases in supply, which has led to skyrocketing home and rental prices. This, in turn, has incentivized many Chico landlords to evict renters and reap large profits by selling their homes. It has also caused many prospective students considering California State University, Chico, to reconsider accepting admission.

California lost nearly 24,000 housing units to fires in 2018. Paradise residents face a lengthy battle in their mission to rebuild their town and their lives, and residents of Chico have nearly lost all hope of a return to normalcy. “The plan is, there is no plan,” says Chico Mayor Randall Stone. “As scary as that sounds, it’s just a world that we have to get used to.”

Fortunately, Mayor Stone is wrong. Despite their hand-wringing over California’s housing crisis, politicians are seemingly doing everything they can to raise home and rental prices by artificially restricting supply, thus reducing access to affordable housing. But this can be reversed. The underlying housing shortage is a government-created crisis, and devising a plan of action to address it requires identifying the mechanisms by which things got so bad and eliminating the barriers to fast and affordable housing construction.

The Pathologies of Government:

A Lesson in Government-Driven Artificial Scarcity and Rising Prices

California’s housing shortage and affordability crisis reveal some unfortunate truths about the effects of government regulations, as well as the abuse of government power. Lawmakers often enact regulations with the best of intentions. But even well-meaning regulations can negatively impact market outcomes. They impose costs that, cumulatively, influence decisions to favor socially harmful results. Meanwhile, the added costs and impediments are pushed by special interests that do not have the interests or priorities of others in mind. This abuse of government power favors politically connected and privileged actors, while suppressing the market incentives and entrepreneurial responses that would otherwise spur efforts to fix the problem.

Then, having created the problem by making it impossible for entrepreneurs to enter the market in sufficient numbers, politicians create government spending programs to ostensibly “rescue” the state from a problem that politicians created themselves. This Alice in Wonderland landscape, where nothing is what it seems, sums up California’s housing mess.

Meeting the housing needs of California residents requires increasing the housing stock, especially multifamily structures such as apartments, condominiums, and SROs. This response, however, is subject to a complex array of costly regulations that come from multiple levels of government.

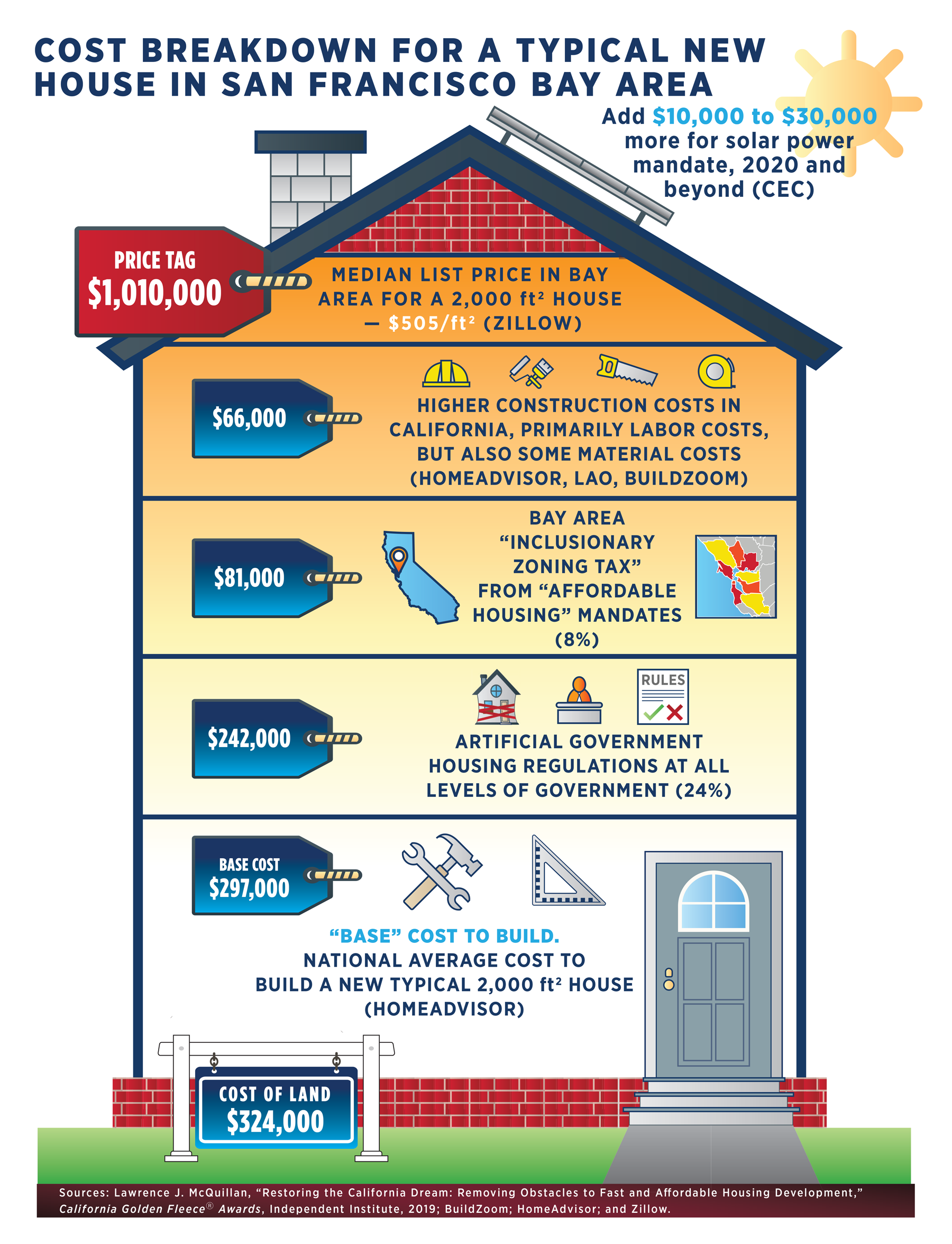

Pervasive regulations imposed by government at all levels make up about a quarter of the price of a new single-family home built for sale, according to a 2016 report published by the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB). According to the report, simply applying for zoning approval contributes an average of 3.1 percent of the final price. Costs charged after construction is approved but before construction begins add another 3.1 percent. Changes in development rules account for 4.4 percent. Compliance with changing building codes over the past decade make up an average of 6.1 percent of the price. And service and impact fees contributed an average of 3.5 percent of the total price.

In addition, regulatory compliance added an average of 6.6 months to the development process, though delays could extend for more than five years, the study found.

A separate 2018 report published jointly by NAHB and the National Multifamily Housing Council (NMHC) found that government regulatory costs average about a third of multifamily development costs. In a quarter of the cases examined, costs associated with the web of regulations surpassed 40 percent. Whether a single-family or multifamily project, these costs, which translate to tens, or even hundreds, of thousands of dollars, are certain to be higher in California, which is “the most heavily regulated state in the country,” according to Granger MacDonald, who served as the NAHB chairman in 2017.

Regulatory costs are inevitably passed on to home buyers and renters, and reduce the supply of housing and drive up its cost. A study by University of California, Berkeley, economists looking at land-use regulations and the California housing market reported a consistent positive relationship between the “degree of regulatory stringency and housing prices for both owner-occupied units and rental units.” More stringent regulations increased housing prices. They also found new housing construction rates were lower in more heavily regulated cities than in less regulated cities, after accounting for a set of other factors. This supports earlier research that has highlighted the cumulative effects of such regulations on housing prices elsewhere in the country. And other studies looking at regulatory roadblocks to development similarly show that they add to housing construction costs and a reduced housing supply.

If the burdensome regulations were cut, substantial improvements would occur, according to several estimates. One study found that rents in more heavily regulated regions are 17 percent higher than in less regulated metropolitan areas; home prices are 51 percent higher; and home-ownership rates are 10 percentage points lower. Another study estimated that metropolitan areas with long delays in development approvals (4.5 months) and tighter growth restrictions experience 45 percent less residential construction than similar areas without these impediments.Removing the obstacles would result in substantially lower rents and home prices, a larger supply of housing, and greater home ownership.

Housing prices are determined by the interaction of supply and demand, and government regulations affecting the supply side of the equation play an important role in California’s housing-affordability crisis. For example, project labor agreements (PLAs), which require the use of more expensive labor, and prevailing-wage laws, which mandate the payment of government-determined wage rates (generally, union pay scales) on government contracts, are often used, or even required by state and local governments, adding a significant amount to already government-inflated housing prices. A 2016 Beacon Economics study of an “affordable housing” ballot initiative with a prevailing-wage requirement in Los Angeles concluded that “prevailing wages are almost double the market rate wages across job classifications and will drive up total project costs 46 percent.”

The lesson is clear: regulations on the development of much-needed housing are costly, delay projects, and reduce the supply of housing and increase its costs—a counterproductive set of effects. The current housing deficit is significant.

California governments have not allowed enough housing to be built to accommodate the residents. The California Department of Housing and Community Development estimates that 180,000 new housing units need to be built each year to, at a minimum, eventually stabilize prices. During the past 10 years, however, the number of new housing units each year has averaged less than half of that, or 80,000 units. But the government’s projection of 180,000 units could be much too low.

The McKinsey Global Institute, a private think tank, issued a report in October 2016, A Tool Kit to Close California’s Housing Gap, and concluded that “benchmarked against other states on a housing units per capita basis, California is short about two million units. To satisfy pent-up demand and meet the needs of a growing population, California needs to build 3.5 million homes by 2025.” That is the equivalent of adding another Los Angeles County worth of housing units, which has a little more than 3.4 million units, or adding about 389,000 units per year for nine years. That would require developers to build housing about five times faster than the current rate in California—an unrealistic goal unless major regulatory changes are made. Every year that California does not reach the target, the housing deficit grows.

Sadly, rather than accelerating housing production, residential building permits are down a shocking 17 percent statewide in the first seven months of 2019 compared to the same period in 2018. In May 2019, multifamily building permits were down a staggering 42 percent from May 2018. In other words, despite reams of political pronouncements, little has changed; in fact, one could argue things have gotten worse. San Francisco added only 2,579 housing units in 2018, the fewest number of new units since 2013.

An important part of the solution must be building more high-density, multifamily housing such as apartments and condominiums in locations where consumers want them, not where governments will allow them to be built. A new report published by the Washington, DC–based Brookings Institution titled Is California’s Apartment Market Broken? “comes down firmly in the ‘build more housing’ camp.” Using new data from the University of California, Berkeley, Terner Center California Residential Land Use Survey on local land use regulations across California, the researchers examine how cities use zoning to deter development of new multifamily buildings.

The researchers conclude, “Too many of California’s high-rent cities have built too few apartments, contributing to the current shortage.... Communities whose residents are hostile towards apartments adopt restrictive zoning laws for a reason: they want to discourage or block development. Turns out, anti-apartment zoning works: cities that set lower allowable densities and building heights built fewer apartments.” One striking example of this is Lincoln, located about 30 miles from Sacramento, which is one of several larger California cities that built more than 1,000 housing units from 2010 through 2018, but did not build a single multifamily housing structure, according to HUD data. In contrast, Irvine in Orange County built the most multifamily units during this period among California’s 200 largest cities.

Many impediments to housing development are pushed by special interest groups that have their own set of priorities that conflict with the goal of increasing the housing stock. For example, many development projects enter into PLAs, favored by labor unions. The PLAs are agreements that establish the terms of employment, including wages and working conditions, prior to bidding by contractors. They may require the use of more expensive union labor, mandate that any nonunion labor be paid union wage rates, or stipulate that nonunion workers must pay union dues during the entirety of the project. Construction under Los Angeles’s Proposition HHH, discussed earlier, is subject to one such government-mandated PLA.

Aside from discriminating against contractors who do not want to be involved with a union, PLAs tend to make construction costs higher. A study looking at construction costs after President Bill Clinton (D) removed a ban on PLAs for federal projects estimated that construction costs would increase up to 7 percent annually. And a number of other statistical analyses have shown that the presence of a PLA on a school construction project increases both bid and construction costs by 20 percent.

Despite the added costs, PLAs are common because they benefit politically connected and powerful labor unions that can deliver votes and campaign contributions to politicians. Union lobbyists, who maintain influence among many politicians, use that influence to advance their own narrow interests at the cost of those who need housing. According to David G. Tuerck, an economist and president of the Beacon Hill Institute who has studied the history and effects of these agreements, “PLAs are motivated by a desire on the part of the construction unions to shore up the declining union wage premium against technological changes and other changes that make traditional union work rules and job designations obsolescent.”

But it is not just unions that impose obstacles to solving the housing crisis. Many homeowner and tenant groups across California have opposed housing development in their neighborhoods. Groups in wealthy, coastal cities such as Los Angeles, San Diego, and San Francisco have provided strong opposition to recent upzoning legislation proposed in the state legislature. And their elected representatives have been listening. As Farhad Manjoo writes in the New York Times, this “‘Not In My Back Yard’ (NIMBY) disposition against allowing new construction projects may be publicly justified as preserving ‘local character’ or ‘local control,’ but at the end of the day the goal is to ‘keep people out’ by ‘keeping housing scarce and inaccessible.’” These actions benefit current homeowners by pushing home prices up as demand continues to increase in the face of an artificially restricted supply, but those in need of housing lose as rents and mortgages skyrocket, making housing less accessible. Some tenant groups oppose new housing, claiming it “gentrifies” neighborhoods.

Improving California’s housing market will require dismantling burdensome regulations and defeating hostile special interests whose priorities are out of step with many people in the state seeking affordable housing options, especially low-income people.

The Recommendations

Many state and local regulations work to delay or stop residential construction projects, or to increase the cost of new construction, the rehabilitation of older buildings, or the conversion of existing buildings into residential housing. These regulations should be eliminated or radically downsized in order to welcome developers, builders, and landlords into the California market to provide housing at all price points. Because of government policies, housing entrepreneurs are not allowed to build the housing demanded by California consumers. This must change if people are to have sufficient access to affordable housing once again.

1. Reduce zoning and land-use restrictions

Zoning rules and land-use restrictions limit the type of housing that developers can build and where they are allowed to build them. These rules take many forms: height restrictions, residential density or occupancy restrictions, limits on multifamily buildings, and explicit growth limits such as caps on permits, moratoria on new development, “green belts” or urban growth boundaries and other limits on developable land. These restrictions increased precipitously in California after the mid-1980s. For example, today “two-thirds of California coastal cities and counties have adopted policies that explicitly limit the number of new homes that can be built within their borders or policies that limit the density of new developments,” according to Matt Levin of CalMatters. Local zoning rules often intentionally limit or ban the construction of multifamily housing or low-cost “prefabricated” or mobile homes, which can make entire regions of the state inaccessible to middle-and low-income people.

Kristoffer Jackson, a financial economist with the US Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, has compared “the rate of construction in [California] cities that implement more land-use regulations to the rate in cities that implement less of it.” Jackson examined data on 402 California cities from 1970 through 1995, and he found that “each additional regulation reduces a city’s housing supply by about 0.2 percent per year [For the average California city,] adding a new land-use regulation reduces the housing stock by about 40 units per year” by cutting new housing construction.

Jackson found that the number of residential permits each year is reduced by an average of 4 percent per restriction: “These reductions in new construction (and the overall housing stock) come through fewer single-and multifamily housing units, but the effect on the latter is much stronger, with an average of 6 percent fewer permits issued per regulation.”

Regarding specific restrictions, Jackson concluded, “One of the most restrictive regulations, caps on residential building permits, reduce construction of single-family homes by roughly 30 percent, while restrictions on the number of new lots created for a subdivision cause multifamily construction to fall by 45 percent. Imposing restrictions on the form of new homes also affects the rate at which they are built: height restrictions (in the form of limitations to the floor-area ratio) can reduce single-family construction by as much as 23 percent.”

Zoning and land-use restrictions should be liberalized, especially in areas with a higher demand for housing. Currently, local zoning laws throughout the state regulate the construction of housing by type in many neighborhoods where additional housing is most needed—particularly, by allowing single-family homes but not construction of multifamily apartment buildings. But these zoning laws have detrimental effects on California’s housing market by constraining supply and thereby increasing costs. To address this problem, cities should deregulate to allow construction commensurate with demand, especially in neighborhoods that are well suited to handle more residents.

Occupancy and density restrictions have decimated the housing stock for low-income residents. Two-to-four unit apartment buildings, rooming houses, boarding houses, “mother-in-law” units, “granny flats,” town houses, row houses, low-rise apartment buildings, duplexes, fourplexes, and single room occupancy (SRO) residences, often in older hotels or apartment buildings, were once common features of towns and cities, especially larger cities. Discriminatory ordinances have caused them to all but disappear over time, often resulting in huge homeless encampments in many cities today. These restrictions have also prevented the conversion of existing buildings into inexpensive multifamily residential structures. Rent control, discussed below, has also produced this negative effect.

Easing zoning restrictions would have the effect of bringing down home and rental prices. Many residents understandably dislike state lawmakers making sweeping decisions that would change the character of their communities. For that reason, it is unsurprising that state-level approaches such as SB 50, which would have forced cities statewide to upzone neighborhoods near a commuter-train or bus station for denser housing projects, have faced strong opposition and have not yet passed the California legislature. SB 50 died in committee in May 2019 and may be revived in January 2020.

Reform by local governments has also died. For example, in July 2019, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors killed a proposed charter amendment that would have made it harder for the public to challenge housing projects, thus accelerating construction. Mayor Breed said the changes could have saved millions of dollars and six to eighteen months per project, but “at the end of the day, process continues to get in the way,” she said. NIMBY opposition is difficult to overcome, but the final recommendation below (#8) discusses some visionary and creative paths forward.

The 2019 California legislative session enacted two bills, AB 68 and SB 13, that incentivize the building of “granny flats” and other accessory dwelling units (ADUs). Another, AB 1486, seeks to expand access to “surplus” government lands for residential housing construction. These bills eliminate some barriers, but much more needs to be done.

2. Streamline building-permit approvals

Housing construction often requires permits or approval from many government bodies: the planning department, health department, fire department, building department, and city council or county board. Lengthy permitting times and costly fees raise the cost of housing construction, and can slow or even stop projects. Brian Goggin with the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at the University of California, Berkeley, examined permitting data from the San Francisco Planning Department from 2009 through 2017. For projects adding 10 or more units, the average time for a development to be permitted was nearly 4 years. The average time for total development (from application to completion) in San Francisco was 6.3 years. But he found that 20 percent of these housing projects take between 10 to 15 years to complete. The notoriously slow pace of approving housing has its consequences. In many parts of the country, a developer can build multiple projects in the time it takes to build one project in California, so they build elsewhere.

As a result, home builders can “build and sell substantially the same house in Texas for $300,000 as they build in California for $800,000,” writes Pete Reeb, a principal at John Burns Real Estate Consulting, in a new analysis. It can take 10 years or more to get a master-planned community approved for development, according to Dean Wehrli with John Burns Northern California. Even subdivisions that are already substantially in conformance with local zoning laws can take three to five years for permit approvals. Permit delays is an important reason why home prices in California are more than 2.4 times higher than in Texas and 2.2 times higher than in Florida.

Keep in mind that each discrete regulation introduces a point of delay into the construction process. According to Ardie Zahedani, president of St. Anton Communities development company, “in communities where there are major restrictions, especially in some communities in Sacramento, some parts of the Bay Area, [construction] can take 10 to 15 years.” Cutting the number of regulations that developers face would go a long way toward alleviating California’s housing crisis in a timely manner.

Permits also slow down so-called affordable housing projects, and the associated fees increase project costs. It took 11 years to build a nine-story apartment building for low-income residents in San Francisco’s Tenderloin neighborhood. City permit fees equaled about $1 million to build 113 apartments and two retail spaces in the building.

Local communities need to streamline the permitting process and eliminate all unnecessary permits and unnecessary steps. One improvement would be to expand by-right designations, which allow projects that conform to existing codes to go forward without lengthy review periods.

3. Abolish the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA)

CEQA is used primarily to stop or delay housing projects. CEQA is responsible for the creation of the new word “greenmail”: unions threaten CEQA lawsuits to extract PLAs from builders; environmental groups use CEQA to force developers to set aside more land for nature preserves; local governments and neighborhood groups use it to blackmail developers into building parks or incorporating other amenities that they themselves will not pay for; businesses use it to harm competitors; and all of these parties use CEQA to try to stop specific projects through endless delays and additional costs.

A 2015 study by law firm Holland & Knight found that only 13 percent of CEQA lawsuits were filed by established environmental organizations, and 80 percent of such lawsuits concerned development in “infill” areas surrounded by existing development, not “greenfields,” the open space or rural areas more likely to be affected by new building. A follow-up study in 2017 found that of the 14,000 Southern California housing units that had CEQA-based challenges, 98 percent of the challenged units were located in existing community infill locations, 70 percent were located within one-half mile of transit services, and “78 percent were located in whiter, wealthier, and healthier areas of the region.”

Statewide, 87 percent target projects in infills, while 12 percent target projects in greenfields. In other words, CEQA challenges have almost nothing to do with the environment. The Legislative Analyst’s Office concluded that CEQA appeals delay a project by an average of two and a half years. Some delays are much longer. Jennifer Hernandez, the director of Holland & Knight’s West Coast Land Use and Environment Group concluded, “CEQA is one of the well-recognized culprits in California’s housing supply and affordability crisis.”

Delays and mitigation mandates drive up costs such that developers back out of projects, which was often the original goal of the parties pursuing CEQA reviews. Many parts of California have open spaces suitable for housing construction, but, as noted by Pete Reeb, “Wide swaths are off limits or require environmental remediation per state [CEQA] laws.”

In 2013, former California governors George Deukmejian, Pete Wilson, and Gray Davis coauthored a piece for the Sacramento Bee calling for CEQA reform: “Today, CEQA is too often abused by those seeking to gain a competitive edge, to leverage concessions from a project, or by neighbors who simply don’t want any new growth in their community—no matter how worthy or environmentally beneficial a project may be.”

Thanks to the San Francisco Chronicle, the public got a rare glimpse into the back-room deals that occur because of CEQA. In October 2019, the San Francisco Chronicle disclosed details of a CEQA settlement between a developer and a neighborhood business owner. Build Inc. had plans to build 1,575 homes in San Francisco’s Bayview-Hunters Point community until a neighbor filed a CEQA lawsuit, claiming the project would obstruct views and block fresh air from the bay. Build Inc. agreed to pay $100,000 to Archimedes Banya, a Russian bathhouse, and pay another $100,000 to Lincoln University, whose president, Mikhail Brodsky, is also owner of the bathhouse, in exchange for dropping the lawsuit and allowing the Bayview housing project to proceed, which had been approved by the city before the lawsuit. The lawsuit delayed the project one year.

In California, virtually any neighbor can stymie a housing project. Attorney Jennifer Hernandez said “Unfortunately, there is a long, unhappy history of CEQA being used as a shakedown machine to leverage cash payments. It’s usually backroom and almost never public.” One experienced San Francisco developer called these payouts to neighbors “construction cooperation fees,” paid in exchange for neighbors’ agreement not to file a CEQA lawsuit. But the payments increase the cost of new housing.

CEQA is a major impediment to residential housing development—arguably the biggest—and, therefore, it should be abolished. It no longer serves its intended purpose. In the words of Ryan Leaderman, an environmental attorney with Holland & Knight, “Completely abolish it, and this is coming from a CEQA attorney! Protecting the environment is very important. In practice, though, at least in highly urbanized areas . . . CEQA has little to do with these ideals.” If abolishment is not an immediate option, allowing infill developments to proceed without CEQA reviews would be a reasonable reform. In the 2019 California legislative session, AB 430 was enacted, which allows for limited sidestepping of CEQA review in eight cities that are rebuilding after the Camp Fire—a clear admission of CEQA’s flaws.

4. Eliminate poorly considered state building codes that needlessly drive up housing costs or eliminate low-cost housing, and transfer decision-making authority to local governments

The California Code of Regulations includes the state building codes. One of California’s newest building codes is the solar panel mandate, which applies to new homes, condominiums, and apartment buildings effective January 1, 2020. The “green-energy” mandate was approved by the California Energy Commission (CEC) in May 2018, and it did not require approval by the state legislature. California is the first state to force new home owners to buy solar panels. The requirement will likely add $10,000 to $30,000 to the cost of a new home.

Steven Sexton, an assistant professor of public policy and economics at Duke University, wrote in the Wall Street Journal that “California’s energy regulators effectively cooked the books to justify their recent command This couldn’t come at a worse time: Rising housing costs are putting the dream of homeownership further out of reach of low-and middle-income Californians.” The solar panel mandate should be abolished.

The CEC also revised the state’s building codes to require stricter energy efficiency for lights, ventilation, windows, walls, and attics. Research fellows James Broughel and Emily Hamilton at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University write in the Los Angeles Times, that energy rules “contribute to staggering construction costs and, in turn, higher house prices. Affordable housing builders spend $400,000 per unit, on average, for new housing in Los Angeles, more than any other city in the country.” Not so fast, reports the Wall Street Journal, which says the cost to build an “affordable” housing unit in San Francisco is nearly $600,000, according to state budget figures. The WSJ says the statewide average cost to build an “affordable” unit is $332,000, clearly not affordable for lower-income residents.

Homes built in California in 2019 and beyond must meet energy-efficiency standards that are 50 percent stricter than the previous 2016 standards. These mandates drive up costs significantly. According to QuantGov, a new database maintained by the Mercatus Center, California has “by far the most regulation of any state in the country.”

In addition to state regulations, some California cities are also using building codes to limit certain fossil fuel use by prohibiting natural gas hookups in new housing. San Luis Obispo charges developers $6,000 for every new housing unit that is not entirely electric.

Building codes also have been used by politicians to deliberately eradicate low-cost housing. Sold as “getting rid of substandard housing” and “improving the lives of poor people,” William Tucker explains in Housing America, “Buildings are condemned as ‘firetraps,’ for not having adequate ventilation, not providing kitchen or bathroom facilities, and for not offering people ‘a decent place to live.’” Too often, the streets become the next home for people forced out of low-cost housing by burdensome codes.

It is past time to eliminate poorly considered state building codes that needlessly drive up housing costs or that eliminate low-cost housing, contributing to the homelessness crisis. Furthermore, the authority to determine building codes should be delegated to local governments. Communities vary widely in California. The concerns of Paradise, for example, are not necessarily the concerns of Los Angeles or San Francisco. Local authority would allow communities the flexibility to adapt to their own circumstances and end inefficient practices. In the 2019 California legislative session, SB 330 was enacted, which temporarily limits some local zoning and building code actions that discourage housing construction. This is a start, but more needs to be done.

5. Eliminate price controls such as rent controls and “affordable housing” mandates, which discourage housing by making it less profitable

A number of California cities have rent control ordinances that limit annual rent increases to a predetermined percentage. The 2019 California legislative session enacted AB 1482, which imposes a temporary statewide cap on annual rent increases of 5 percent plus the inflation rate. The cap will be in effect from 2020 through 2030. But economists have long known that rent control does much more harm than good. These controls should be eliminated in favor of market-based pricing.

Rent controls that keep rents below market rates create an excess demand for rental units, also called a shortage. The shortage becomes worse over time as demand for rental units increases. Initially, in response to binding rent controls, landlords reduce maintenance of their buildings to reduce their costs, causing a prolonged deterioration of the housing stock. Long term, landlords convert apartments to condos to escape the rent controls or abandon the buildings altogether, further shrinking the stock of rentals. In many American urban areas, it is common to see block after block of abandoned, boarded up buildings, victims of rent control and magnets for crime.

Decades of economic studies show that rent controls have a counterproductive effect on housing markets. Matthew E. Brown, economics professor at the University of Illinois, Springfield, lists these among the consequences: “shortages of apartments for rent, decreases in quality and lack of maintenance, decreased construction of new apartments, long waiting times and high search costs [to find apartments], discrimination, homelessness, abandoned buildings, and labor market inefficiencies.” These are precisely the problems currently plaguing California’s housing market, particularly at the lower rungs of the housing ladder. As noted by Walter E. Williams, professor of economics at George Mason University, “[S]hort of aerial saturation bombing, rent control might be one of the most effective means of destroying a city.”

A variation on rent control that also reduces the housing stock is inclusionary zoning—often called “affordable housing mandates”—which are ordinances that require a builder to set aside a portion of a new development, typically 10 to 25 percent of the units, to be sold at below-market prices to individuals with moderate, low, and very low incomes. But placing price controls on a percentage of new homes lowers builders’ profits from new developments by acting as a tax on building new homes. And like any tax, it reduces the supply—in this case, new homes—while raising the price of the new noninclusionary units and existing homes. Builders, landowners, and market-rate home buyers pay the “inclusionary tax.”

Benjamin Powell and Edward Stringham, economists and fellows with Oakland’s Independent Institute, studied the effect of inclusionary zoning in California from 2003 through 2007. More than 170 communities across the state impose inclusionary mandates. The economists found that “affordable housing mandates” make the vast majority of housing less affordable. In the Bay Area, for example, cities with inclusionary zoning ordinances imposed an average effective tax of $44,000 on each new home. With the median cost of a new home at the time slightly more than $500,000, this amounted to an 8 percent “tax.” In Los Angeles and Orange counties, the average effective inclusionary tax was $66,000 per new home—about 12 percent of the average median new-home price at the time (approximately $550,000).

Inclusionary zoning also reduces the construction of new homes. After adopting inclusionary ordinances, housing production on average decreased by more than 30 percent in the first year in Bay Area cities. In Los Angeles and Orange counties, housing production decreased 61 percent over a seven-year period following adoption. Also in Los Angeles and Orange counties, during the period studied, more than 17,000 potential new homes were never built due to the inclusionary zoning requirement, while only 770 inclusionary units were added—a net loss of housing, making the housing shortage worse. After passing an inclusionary ordinance, the median city in Southern California produced less than eight affordable units per year. Clearly, inclusionary zoning is not a solution for the housing crunch. “Affordable housing” mandates are not “compassionate,” rather they act as a tax on new housing construction and make housing less affordable and less available, benefiting people who already own homes.

Zoning, building codes, and rent controls have combined to destroy low-income housing in neighborhoods where people need very low-cost housing. As a result, many of these people end up homeless, typically in public spaces: parks, medians, greenbelts, sidewalks, and road and path rights-of-way, where property rights are ill-defined and public officials choose not to enforce vagrancy laws. As argued by Ryan McMaken of Auburn University’s Mises Institute, “[I]f San Francisco had not demolished much of its lowest-priced housing over the past fifty years, the volume of people now living on sidewalks would not be as large.... The problem we encounter today is that cities have largely destroyed much of their earlier-existing housing stock that catered to very-low-income populations, and have imposed restrictions that prevent construction of new housing that could be suitable.”

The solution is more housing across the price spectrum, and market pricing is an important component to achieving that goal—not price controls and discriminatory government policies that reduce housing availability.

6. Eliminate regulations that drive up costs of homebuilding such as PLAs and expensive development impact fees

The Legislative Analyst’s Office has reported that construction labor in major California cities is 20 percent more expensive than in the rest of the country, and local development fees averaged more than $22,000 per single-family home, about three-and-a-half times the national average of $6,000, with the differential being much greater in some California cities. These added costs reduce the supply of housing and put home ownership out of the reach of more Californians.

As discussed earlier, project labor agreements, prevailing-wage mandates, and other union protections that attenuate freedom of contract between employers and employees, and that permit the disruption of housing projects if union demands are not met, drive up labor costs in California. One solution would be for California to become a right-to-work state where the terms of labor contracts are the result of voluntary negotiations.

At the city level, service fees are imposed for planning and building, and impact fees are imposed to pay for schools, parks, roads, water systems, and other capital improvements. These fees increase the cost of new housing. In some areas of the state, homebuilders typically pay $25,000 to $75,000 in local fees to build a single home. In the city of Fremont in 2017, government fees per home totaled nearly $160,000 on the $850,000 median value of a single-family home. Development fees (city service fees and impact fees) add 6 to 18 percent to residential construction costs in seven California cities. In San Francisco, market-rate developers point to astronomical city fees that make many housing projects impossible to finance.

In an August 2019 report, researchers at the Terner Center found that local impact fees vary widely across localities. They compared fees for transportation, environmental mitigation, fire and public safety, libraries, parks, housing, capital improvements, and utilities on a prototypical project in 10 California localities. The fees on a typical project varied across locations by as much as $19,100 per unit on apartments and other multifamily projects, and nearly $30,000 per unit on single-family homes.

Sometimes fees are determined after a project is well underway, rather than early on, making it difficult to arrange financing. Unexpected fees can be tacked on, making a housing project intended for low-income people only affordable for wealthier people.

It is folly to believe it is possible to calculate each individual project’s actual impact and assign an accurate fee. New development should fully pay its own way, but a simpler approach is to eliminate impact fees and use private provision of services (this is discussed more in recommendation #8).

7. YIMBYism: Allow entrepreneurs to enter markets and provide housing solutions at all price points

Since the 1980s, California has been increasingly captured by NIMBY groups, politicians, and regulators. A shift to YIMBYism (“Yes in My Back Yard”) would free entrepreneurs to help solve the housing problem. Entrepreneurs would provide fast and affordable housing in the Golden State, if only they were allowed to enter markets, compete, and build units in the locations and at the price points demanded by consumers. Entrepreneurs can provide many innovative solutions.

Builders of modular or “prefabricated” homes, for example, offer the possibility of faster and lower cost construction of single-family housing units. Modular homes are built in sections inside factories rather than outdoors on site. This allows them to be built quicker and at lower cost due to fewer delays. Unlike “manufactured homes”—a category that includes mobile homes—modular homes are assembled on a permanent foundation, and are as durable as traditional site-built homes.

Their quality, cost, and speed of assembly make modular construction an attractive option for residents of communities like Paradise that are rebuilding after recent destructive wildfires, as well as cities such as Los Angeles that are trying to tackle a severe housing shortage. Hybrid Prefab Homes has already assembled homes for victims of the Tubbs Fire in Santa Rosa. The company estimates their modular homes cost about 20 percent less than similar homes constructed using traditional methods, and on average can be completed in about half the time. Other companies, such as Blu Homes in Vallejo, CleverHomes in Oakland, and SageModern in San Francisco, sell modular homes across the state, and offer an avenue for more efficient construction, which is desperately needed to combat the housing shortage. In Los Angeles, for example, the Proposition HHH Citizens Oversight Committee has been exploring the idea of installing prefabricated housing to speed up construction of housing that was promised by local officials but not a single unit has yet been completed.

Other innovations include so-called “tiny homes” and futuristic 3-D-printed homes. Tiny homes are very small units, usually 400 square feet or less, that are inexpensive and have a small footprint so more units can be placed on a plot of land. The typical price range to construct a tiny home is $10,000 to $20,000. Tiny home companies in California include California Tiny House and Seabreeze Tiny Homes both in Fresno, Sierra Tiny Houses in Sacramento, and Tiny Mountain Houses in Roseville.

Seattle has eight tiny home villages featuring 328 tiny homes for homeless people. Each village accommodates up to 70 people, costs up to $500,000 to build, and are constructed in just six months. Each tiny home has a locked door, bed, microwave, toilet, and sink. San Francisco officials have rejected tiny homes for the homeless because, among other reasons, unions object to houses being built by non-union labor (often by volunteers).

3-D-printed homes are in their infancy in terms of commercial viability, but with technological advances, 3-D-printed homes will likely become common. These homes are built using massive printers. Every year new companies enter the 3-D-printed home market. New Story, a charity based in the Bay Area, began building communities of homes around the world in impoverished areas. Later they partnered with ICON in Austin, Texas, a 3-D-printing technology company. New Story and ICON have built practical, livable homes that are also remarkable feats of engineering. As a nonprofit, New Story’s objective is to fight homelessness, and to that end, they share all their techniques and expertise on their website, along with testimonials from satisfied tenants. New Story and ICON can make 3-D-printed homes at blistering speed. Their proof-of-concept home, and first permitted 3-D-printed home in America, was built in Austin, Texas, in March 2018 and unveiled at South by Southwest. It cost about $10,000 to build (printed portion only) and took approximately 48 hours to build. The goal is to complete entire units on site in 24 hours at a cost of about $4,000 each, paid back via a zero-interest loan. New Story is currently working on building the first community of 3-D-printed homes. ICON is building 3-D-printed structures for Austin’s homeless and has plans to build middle-class housing in central Texas.

In addition to New Story and ICON, Shanghai-based Winsun Decoration Design Engineering Company is pushing the limits of scale and imagination in 3-D-printed buildings. Not satisfied with making small homes, they have used 3-D printers to create an entire apartment building, a mansion, an office building in Dubai, and the world’s tallest 3-D-printed building, along with having once built ten houses in one day. They claim to be able to build a house in less than twenty-four hours for as little as $5,000. Winsun is pushing the envelope of creativity and imagination regarding the future of 3-D-printed structures.

Other builders specialize in massive high-rise apartment and condominium structures, which would be sensible for some parts of California. These builders include Concord Pacific, which built the Concord Pacific Place, Canada’s largest master-planned urban community and the inspiration for the Dubai Marina. Daewon Plus Construction, Doosan Engineering & Construction, and Hyundai Development Company, all South Korean companies, have built multiple residential skyscrapers. As land prices increase in California, one way to lower the land price per housing unit is to use the vertical space above land more intensely in order to build more units where consumers want them. But height and density restrictions in many California locations outlaw large-scale application of residential skyscrapers.

At the other end of the spectrum is Rent the Backyard, a startup that builds backyard studio apartments and splits the rental income with homeowners. The company launched in the Bay Area, but hopes to be nationwide eventually. It says that homeowners in the Bay Area can pocket between $10,000 and $20,000 each year in additional income by hosting a small, backyard apartment. Rent the Backyard arranges the financing and handles the paperwork. Its cofounder and CEO Brian Bakerman told Yahoo Finance that the process from filing permits to completing construction takes about four to five months, at which time “a homeowner can start seeing rental income.”

As this discussion shows, entrepreneurs offer many creative solutions to the housing crisis if governments allow them to do so. One San Francisco nonprofit is trying to create more opportunities for entrepreneurs to solve the Bay Area’s housing crisis. The California Renters Legal Advocacy and Education Fund (CaRLA) is pursuing a “sue the suburbs” strategy. Founded by Sonja Trauss, CaRLA files lawsuits against California cities that reject housing projects that are compliant with the city’s general plan and zoning rules, using the state’s Housing Accountability Act as its legal justification.