A proposal made in January by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services would cause almost 14 million seniors to lose their Medicare Part D stand-alone drug plans next year, essentially banning the most popular Medicare drug plans by 2015.

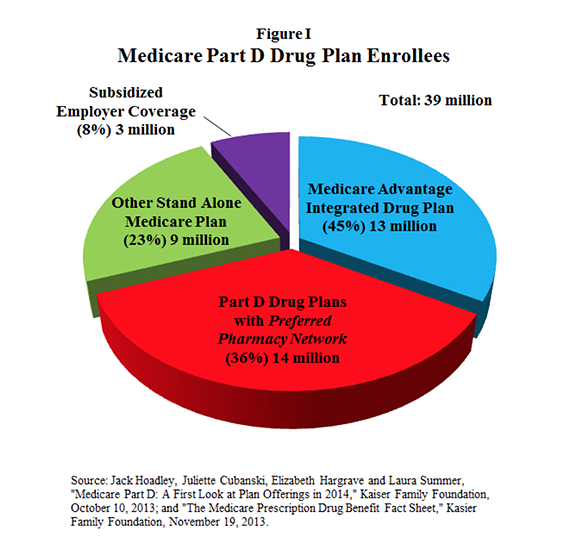

Nearly 39 million Medicare beneficiaries, including both seniors and the disabled, have subsidized drug coverage through the Medicare Modernization Act (MMA) of 2003. Of these, nearly 36 million individuals are enrolled in drug plans known as Medicare Part D. [See Figure I.]

However, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has proposed new regulations that would eliminate the most popular plans: ones that offer seniors lower premiums (and lower cost sharing) in return for patronizing a preferred pharmacy network. Many seniors have stand-alone drug plans—meaning they are not integrated with a health plan. An estimated 75 percent of the seniors with stand-alone Part D drug coverage are in plans that feature a preferred pharmacy network. That is a significant jump from 2013, when only about 43 percent of stand-alone plans had such networks. If preferred networks are banned for 2015, nearly 14 million seniors will lose their current drug plans.

The Medicare drug program has been quite popular. Participating seniors pay about one-fourth of the cost, and the government pays the rest. As a result, the portion of seniors who lack drug coverage has fallen 60 percent since the Medicare Modernization Act was passed. Overall, seniors are highly satisfied with their drug plans. Satisfaction rates average about 90 percent to 95 percent.

A likely reason seniors give their drug plans high marks is because they can choose among a wide range of plans. The number of options varies among states, from a low of 28 in Alaska, to a high of 39 in Pennsylvania and West Virginia. Enrollees can select plans that feature premiums as low as $15 per month, but require significant cost-sharing, or ones that are much more expensive, but require little out-of-pocket spending. On average, seniors choose plans that cost about $38 per month.

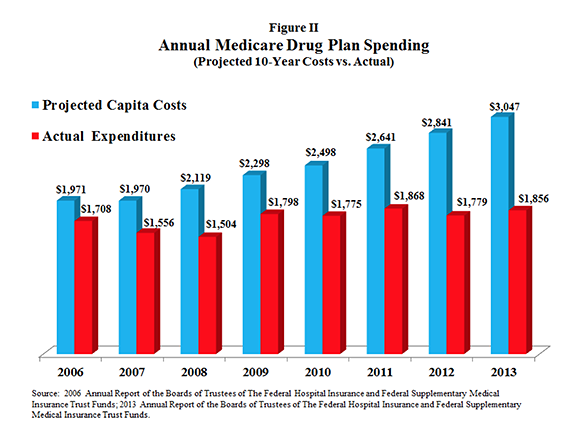

Though subsidized by Medicare, the premiums seniors pay are a function of the plan they choose—and ultimately of total program expenditures. Premiums have remained relatively stable because drug spending per member has been far lower than projected.

As Figure II shows:

- Nearly a decade ago the Medicare Trustees projected a per capita benefit cost of $1,971 in 2006, rising to $3,047 by 2013.

- But the actual per capita cost in 2013 was only $1,846—nearly 40 percent lower than initial projections.

Some Medicare officials remain skeptical of the original design of the Medicare Part D drug program—which was passed by the Bush administration with the help of congressional Democrats. From its inception, the MMA has included a non-interference clause that prevents the government from intruding on contract negotiations between drug makers, pharmacy networks and drug plan sponsors. Congress and the Bush Administration wanted the Medicare drug program to be composed of private drug plans that vigorously compete for seniors’ patronage.

Under the 2003 law, drug plans use a variety of techniques to keep premiums affordable, including preferred-drug lists, tiered formularies and mail-order drug suppliers. Drug plan sponsors negotiate prices with drug companies and drug distributors, and contract with pharmacy network providers to secure seniors the lowest possible drug prices. That is, until now.

Last month, CMS proposed new regulations that would restrict the ability of drug plans to offer seniors lower drug prices in return for patronizing preferred networks. Medicare Part D drug plans have increasingly adopted exclusive preferred pharmacy networks, giving them leverage to negotiate the lowest possible drug prices.

The Obama administration wants to block drug plans from excluding the losing bidders—drug provider networks that offered higher prices in contract negotiations. The proposed regulatory change is not benign; it weakens a drug plan’s power to bargain for lower prices. Without the knowledge that a “losing bid” risks losing out on all potential business for a given Medicare drug plan, pharmacy networks will have little reason to make price concessions. The actuarial firm Milliman contends this proposed regulatory change will actually cost the Medicare program nearly $1 billion per year, adding more than $9 billion to the cost of the program over the next decade.

Seniors seem to appreciate drug plans that feature low-priced, preferred pharmacy networks. Nearly six-in-10 Medicare Part D plans feature preferred pharmacy networks. These plans are among the most popular, covering approximately 14 million seniors nationwide. Seniors—and taxpayers—will pay higher prices for their medications if they lose this option.