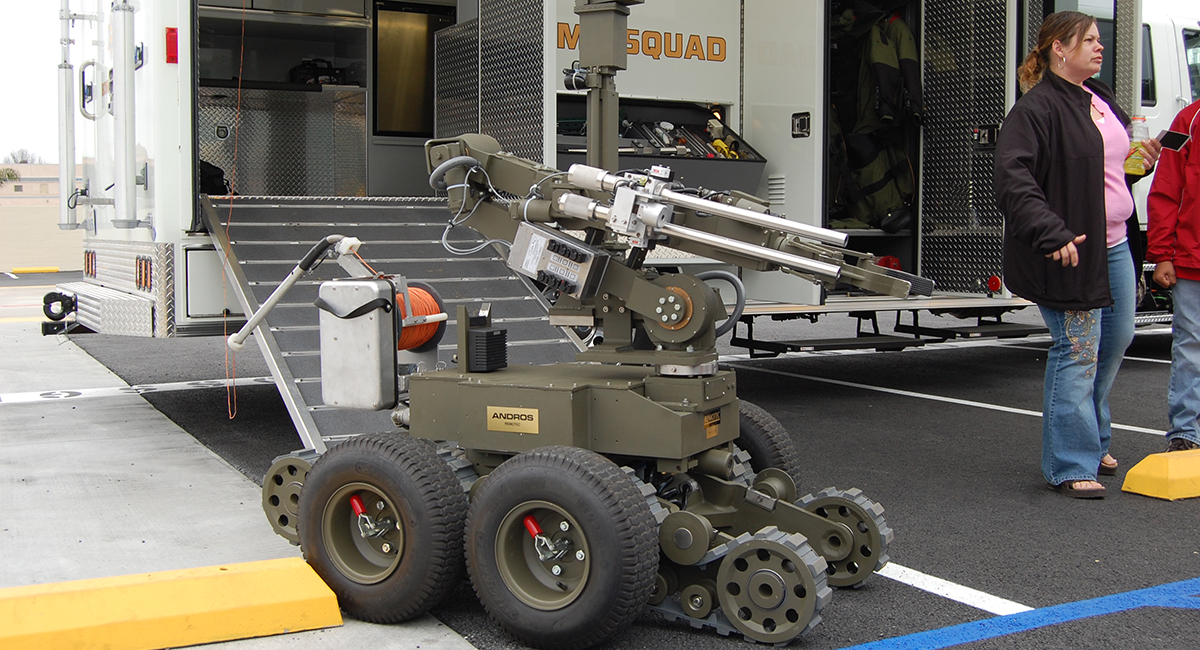

Police in San Francisco can now use robots to kill people.

In an 8-3 vote by the city’s Board of Supervisors, the new policy grants the SFPD power to use lethal force via remote controlled robots. According to the police department it would now have the ability to deploy robots equipped with explosive charges “to contact, incapacitate, or disorient (a) violent, armed, or dangerous suspect” when lives are at stake, SFPD spokesperson Allison Maxie said in a statement.

These new powers are supposed to be limited to emergency situations, “when risk of loss of life to members of the public or officers is imminent and outweighs any other force option available to SFPD.”

Don’t count on it.

There is real reason to believe that the use of these “killer robots” will expand. Why? The answer lies in simple economics, and in the increasing militarization of our domestic law enforcement.

First, consider the supposed constraints faced by the SFPD. While the above statement suggests a very narrow set of circumstances in which the technology may be used, it’s actually remarkably broad.Consider the language used just prior to the sentence above, “[the robots] shall not be utilized outside of training and simulations, criminal apprehensions, critical incidents, exigent circumstances, executing a warrant or during suspicious device assessments.”

Instead of limiting the number of scenarios in which these technologies may be deployed—these broad categories—“criminal apprehensions,” “executing a warrant,” etc., means that robotics technology may be used in a myriad of cases, not a few. As Matthew Guariglia of the Electronic Frontier Foundation noted, this language affords police the ability to bring robots to any and all arrests and to public gatherings such as protests. This risk was evident during the George Floyd protests where police used drones to surveil protests, sonic weapons to control protestors, and shows of force to intimidate protestors.

In addition to these loose constraints, the current policy provides no details on how decisions will actually be made on when to deploy robotics technology or to the use of lethal force other than to see the Police Chief must give the order and must first consider alternatives. There are no details on what checks and balances will be put in place to ensure accountability.

Some of these potential issues with the killer robots became clear during the debate prior to the vote on the policy.

Proponents of the policy insist it can help save lives. In the debate prior to the policy’s passage, the Assistant Police Chief suggested that killer robots would have been useful in assisting police during the Nevada shooting at Mandalay Bay in 2017. But again, we see a complete lack of planning or rules of planning. How would these robots be deployed in such a scenario? How would police avoid harm to innocent bystanders in a situation with crowds, hostages, etc.? As opposed to a clear guideline for use, stating the technology may only be used in the case of “imminent threats” is extremely difficult to discuss in the abstract, let alone during a live police situation.

People may say that concerns regarding overuse or inappropriate use are overblown. But this fails to understand the history of police use of technology.

Consider, for example, the evolution and use of SWAT teams. These police units, utilizing specialized military training and tools, were formed with promises that they would be used only in very rare situations—when extreme threats and emergencies could not be handled by traditional policing.

In practice, the use of SWAT has massively expanded through time. There are numerous indications that SWAT units are frequently deployed in cases where there is no emergency situation with an imminent threat to life. Today, SWAT teams are deployed for a wide-range of activities including executing drug warrants and responding to threats of suicide. Instead of defusing the situation, they often leave a trail of blood and destroyed property behind them.

The reality is that police departments behave like any other unit of government. They face incentives to increase the scope of their activities through time to increase their budgets and expand their forces. As the case of SWAT makes clear, this same logic applies to the militarization of police—including militarization involving the integration of advances weapons technologies. Because of the lack of direct accountability, there is an incentive to act first and ask questions later.

Moreover, the debate over the use of killer robots is the latest manifestation of broader concerns over the militarization of domestic policing. The debate is unlikely to end anytime soon. As we have argued elsewhere, military activity abroad often returns home, ending up in the hands of domestic law enforcement agencies for use against the populace. Given trends in robotic warfare, there is reason to believe we will see more cases of the use of these technologies at home.

While San Francisco has opted to use these weapons, their expansion is not inevitable. In October 2002, police in Oakland, California, sought authority to use a robot capable of firing shotgun ammunition. The department reversed course after public backlash against the plan. Public pressure, as we have seen over the last two years, is a key check against expansions in the scope of policing activity. While police can use technology to protect the person and property of citizens, they can also use those same technologies to undermine Constitutionally-protected liberties. This suggests that the bar for adopting such new methods should be extremely high with the burden falling on proponents of these policies.