The political left’s love affair with steep progressive taxation got an academic boost with the publication of Thomas Piketty’s bestselling 2014 book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Appealing to the New Deal era, Mr. Piketty proposed a simple explanation and remedy for rising economic inequality: The concentration of income among the top 1% could be mitigated by strategically targeting wealth with the tax system.

Mr. Piketty based his theory on a historical argument taken from his own empirical work with fellow economist Emmanuel Saez. When Congress and President Franklin D. Roosevelt hiked the top marginal income-tax rate to 91% during the New Deal and World War II, they allegedly broke up the concentration of the capital stock at the top of the income ladder. Inequality declined to a midcentury trough, where it remained until the Reagan tax cuts in the 1980s. Inequality then rebounded to form a centurylong U-shaped pattern. The solution, then, is to restore tax rates to their FDR levels.

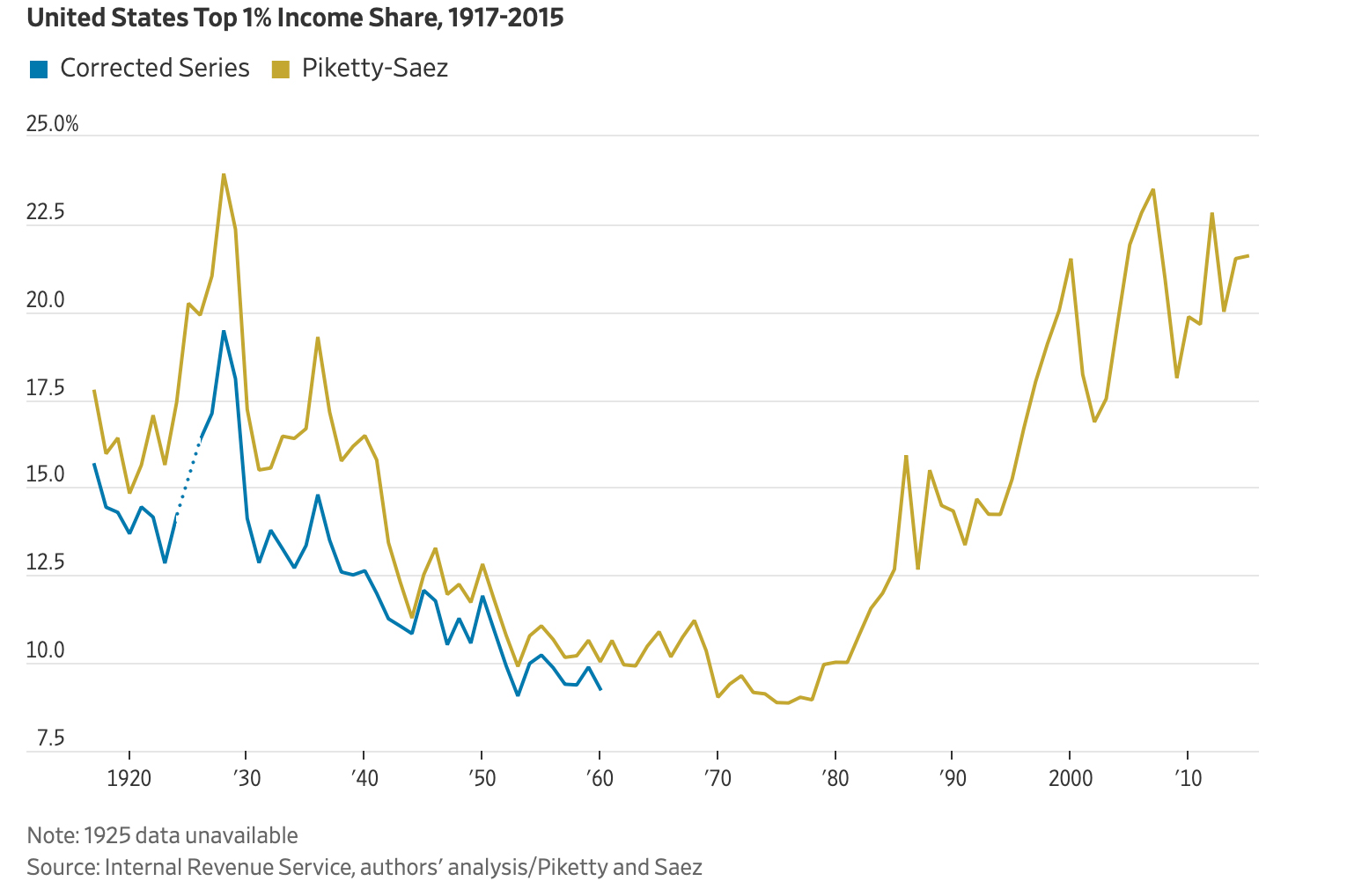

But the Piketty-Saez theory is less a matter of history than an accounting error caused by their misunderstanding of World War II-era tax statistics. That’s the main conclusion of a new analysis of top income concentration in the U.S. between 1917 and 1960, which we recently published in the Economic Journal.

Progressives embraced Messrs. Piketty and Saez’s historical account after it appeared in an influential academic paper in 2003. Their story undergirds the wealth-tax proposals of Sen. Elizabeth Warren and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. Heather Boushey, a member of President Biden’s Council of Economic Advisers, is also a fan. Even the New York Times’s “1619 Project” draws on Messrs. Piketty and Saez to proclaim confidently that “progressive taxation remains among the best ways to limit economic inequality.”

Our findings paint a different picture. It’s true that income inequality declined in the early part of the 20th century, but the cause had more to do with the economic devastation of the Great Depression than the New Deal tax regime.

To see how, we must first turn to Messrs. Piketty and Saez’s inequality statistics. Their data show a rapid decline in top income shares between the 1929 stock-market crash and the end of World War II—a period economists have dubbed the “Great Leveling.” In their version, the sharpest decline took place between 1940 and 1945, just as the 91% top marginal rate schedule became a fixture of midcentury tax policy. Their statistics imply that more than 34% of the decline in the top 1%’s income share occurred in this brief period, as did an astounding 73% of the decline in the top 10% of earners.

Our investigation of the Piketty-Saez data reveals that they failed to account properly for historical changes in how the Internal Revenue Service reported income-tax statistics. As a result, their numbers systematically overstate the levels of top income concentrations by as much as a third, while also distorting the trend line during the “Great Leveling” period. The combination of these errors creates an illusion that FDR’s tax hikes caused inequality to fall.

Messrs. Piketty and Saez’s mistakes arise from how the IRS tabulates income. Between 1943 and 1944 the tax collection agency shifted from tracking “net income” to “adjusted gross income,” or AGI. The latter category, a truer depiction of annual earnings, includes both taxable earnings and deductible income such as charitable giving and state and local tax payments. Yet Messrs. Piketty and Saez didn’t bring pre-1944 IRS records into line with AGI accounting standards. Instead, they applied a fixed and arbitrary adjustment to all years before the AGI accounting change that conveniently scaled upward to the highest income brackets.

At the same time, Messrs. Piketty and Saez mishandled how they estimate the top 1%’s income shares. In addition to IRS records of tax payments, this calculation requires a measure for all personal income earnings. We found that in every year prior to 1960, the IRS’s numerator is mismatched to the total income denominator used by Messrs. Piketty and Saez. They used the wrong accounting definition for personal income and neglected to adjust their data for wartime distortions on tax reporting. When we corrected these problems, something stunning happened. The overall level of top income concentration flattened, and the timing of its leveling shifted away from the World War II-era tax rates that Messrs. Piketty and Saez place at the center of their story.

The nearby chart shows the results for the top 1% of income earners. In our series, inequality rose between 1917 and 1928, confirming the “Roaring ’20s” boom. The crash of 1929 emerges as the precipitating event of the “great leveling”—mainly due to severe capital losses among the wealthy during the Depression.

These events predate the alleged inequality-reducing effects of high progressive taxation. The first Depression-era income tax hikes weren’t enacted until 1932. The policies that Messrs. Piketty and Saez wish to emulate became permanent during World War II, when Congress expanded federal income-tax eligibility and aggressively ramped up enforcement through automatic payroll withholding.

The 1929 drop is hard to celebrate, as it involved a downward leveling for everyone. It’s possible that FDR-era tax policies contributed to a leveling that was already under way, but these effects are muted in comparison with what Messrs. Piketty and Saez assume. When combined with other revisions to questionable claims in the post-1960 portion of the Piketty-Saez inequality data, a different centurylong pattern emerges. Instead of an inequality U-curve, in which income concentrations sharply fall then rise again as a direct inverse of federal income tax rates, we find a pattern that resembles a shallow saucer. Inequality does change over time, but at a much more subdued level. The causes of the shifts are related to macroeconomic events, such as the Depression, and conventional economic factors, such as increased labor and capital mobility.

These findings should provide a warning to policy makers who imagine that they can design a more equitable distribution of income by simply pulling the levers of fiscal policy. The assumed relationship between high rates and low inequality has attained a position of dogma among those who seek to rationalize a preference for tax hikes. In reality, it may be an artifact of poor statistical methodology and careless data treatment.