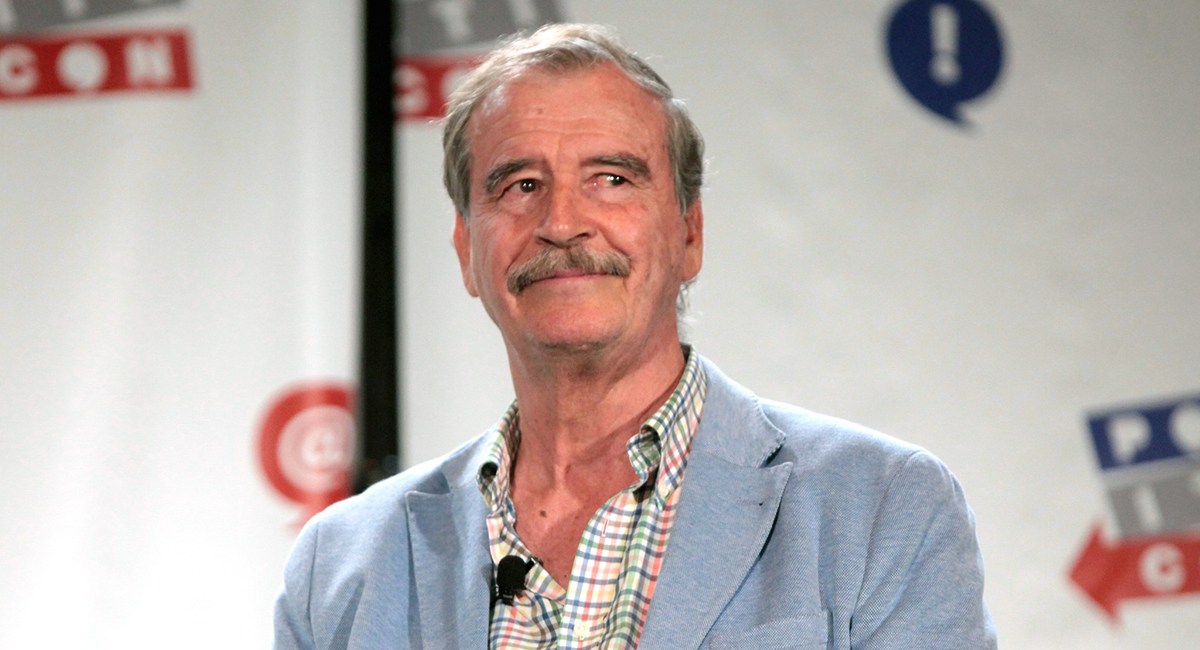

Mexican President Vicente Fox today begins an official state visit with George W. Bush. Now, more then ever, is the time for the U.S. to reach out a helping hand to Mr. Fox and Mexico.

For those who have longed for closer U.S. ties with our southern neighbor, today’s meeting is a reason for jubilation. The elections last year of both Mr. Bush and Mr. Fox marked the beginning of a new era. The two presidents—both former governors of states deeply affected by migration—have set out in earnest to deal with bilateral issues. They have sought to parlay their personal friendship into a prosperous partnership for both nations.

Severe Criticism

But even as Mr. Fox is feted in Washington this week, he faces severe criticism back home. The two main opposition parties—the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), and the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD)—have complained of “frustrated expectations” and accused Mr. Fox of reneging on campaign promises for economic growth and social reforms. Even his own National Action Party is disturbed over the lack of entrepreneurial incentives in Mr. Fox’s taxation package.

Can President Fox bridge the seeming disconnect between the adoration he garners in the U.S. and the cynicism emerging in Mexico? How far is President Bush willing to go to help him—and what is at stake for America?

What Mr. Fox has achieved in the nine months since coming to office is impressive. Early on, he extolled budgetary discipline and responsible monetary policy as necessary for Mexico’s economic salvation; he embraced standards similar to the European Union’s Maastricht criteria for defining when Mexico would qualify for “convergence” with Canada and the U.S., its North American Free Trade Agreement partners.

So far, Mexico is meeting, or exceeding, the targets. Its budget deficit is hovering at about 0.65% of gross domestic product after diminished tax revenues compelled the Fox administration to reduce spending twice already this year. Following a bout of early tightening by the Banco de Mexico, the nation’s central bank, the interest rate on short-term government debt dropped to around 7% in recent weeks—“truly historic” levels, as Mr. Fox notes.

As for inflation, Mexico seems finally to have come to grips with its perennial nemesis. Addressing a group of high-powered business leaders in Sun Valley in July, Mr. Fox could not resist mentioning that inflation in Mexico for the first half of the year was lower than in the U.S.

U.S. investors are responding positively, as reflected in the rising peso—it has become the world’s strongest performing currency against the dollar—as foreign direct investment flows are predicted to reach a record $20 billion this year, powered by Citigroup’s acquisition of Banamex.

The bad news is that Mexico has been hit hard by the global economic slowdown—in particular, by the sluggish U.S. economy, which normally absorbs close to 90% of Mexican exports. Instead of the 7% economic growth rate Mr. Fox had hoped to achieve, Mexico’s gross domestic product is likely to increase by less than 1% this year. Oil, which accounts for 37% of government budget revenues, has been pummeled by lower prices and reduced exports. Unemployment is rising; the 1.3 million new jobs Mr. Fox had anticipated have turned into the loss of some 400,000 existing jobs.

No one is more disappointed about this turn of events than Mr. Fox, who first got an inkling of bad times ahead from Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan last November. Responding to Mr. Fox’s glowing admiration for the high-growth, low-inflation performance of the U.S., Mr. Greenspan, who was attending the Banco de Mexico’s 75th anniversary conference, hinted that the trend might not continue. The Fox administration has reluctantly ratcheted down its growth forecasts.

What can the U.S. do to help Mexico at this point? First, we could turn around our own anemic growth performance. We, of course, don’t need outside motivation to do so, but any debate over the implications of U.S. fiscal and monetary policies with regard to global leadership should start by recognizing that the economic fate of 100 million Mexicans rests on the wisdom of those decisions.

Meanwhile, President Fox gamely points out that a stable Mexico has managed to “cushion the negative effects that in other eras caused a full-blown collapse” and exhorts his fellow citizens “not to lose hope” in the dream of a better future. But he cannot put off the promise of growth indefinitely. His enemies are already circling, with former PRI presidential opponent Francisco Labastida saying that Mr. Fox’s close relationship with Mr. Bush amounts to “words, not deeds.” And Cuauhtemoc Cardenas, former PRD presidential candidate, taps into latent anti-Yanqui sentiment with his accusation that the Fox administration is doing the “dirty work” for the U.S. in trying to reduce emigration from Mexico and Central America.

The irony is that immigrant workers from across our southern border have never had a stronger champion than Mr. Fox, who hails them as heroes who incur great risk and hardship to improve the economic prospects of their families back home. Such thoughts are echoed by Mr. Bush, with his observation that people who are “willing to walk across miles of desert to do work that some Americans won’t do” should be treated with respect.

If the moral factor weren’t enough, there are also economic reasons for both presidents to forge meaningful immigration reform as the centerpiece of this week’s summit. For the U.S., the inflow of foreign labor diffuses wage pressures; for Mexico, the inflow of capital from workers, who remit home some $8 billion annually, raises living standards and provides the nation with its third-largest source of income.

On the contentious issue of trucking, Mr. Bush has made it clear he is willing to risk his own political capital to allow Mexican trucks on U.S. roads by early 2002. Not only does this position comply with Nafta obligations, it reinforces the Bush administration’s commitment to free trade. To disillusion Mexico about the mutual benefits of open markets would be to lose our best ally in championing the broader agenda for free trade throughout the Americas.

To be sure, President Fox has work to do to prove his own free-market credentials. His fiscal reform proposal, which expands the value-added tax and punishes investment, is more obsessed with raising immediate revenue than establishing long-term, pro-growth policies. Moreover, Mr. Fox still seems too tentative in his dealings with Pemex, the state-run oil company; despite the obvious synergies to be gained if private foreign investors were allowed to supply needed capital, he vows to preserve its government monopoly status.

Ideological Convictions

In pursuing his vision for North American convergence, too, Mr. Fox is guided more by a socialist European Union approach than a simple dismantling of trade barriers. He wants the U.S. to largely foot the bill for Mexican infrastructure projects in the name of “regional development,” financed through an enlarged North American Development Bank.

But these differences should not distract from the deeper ideological convictions shared by President Bush and President Fox—namely, that growth and opportunity nourish the spirit of democratic capitalism. Both leaders believe that closer hemispheric relations must be predicated on the doctrine of free people and free markets. And both are dedicated to forging a successful relationship to serve as prototype for a new American century.