With the end of the twentieth century rapidly approaching, this is a time to look back and gain some perspective on where we stand as a nation. Were the Founding Fathers somehow to return, they would find it impossible to recognize our political system. The major cause of this transformation has been America’s involvement in war and preparation for war over the past hundred years. War has warped our constitutional order, the course of our national development, and the very mentality of our people.

The process of distortion started about a century ago, when certain fateful steps were taken that in time altered fundamentally the character of our republic. One idea of America was abandoned and another took its place, although no conscious, deliberate decision was ever made. Eventually, this change affected all areas of American life, so that today our nation is radically different from the original ideal, and, indeed, from the ideal probably still cherished by most Americans.

The turning point was signaled by a series of military adventures: the war with Spain, the war for the conquest of the Philippines, and, finally, our entry into the First World War. Together, they represented a profound break with American traditions of government.

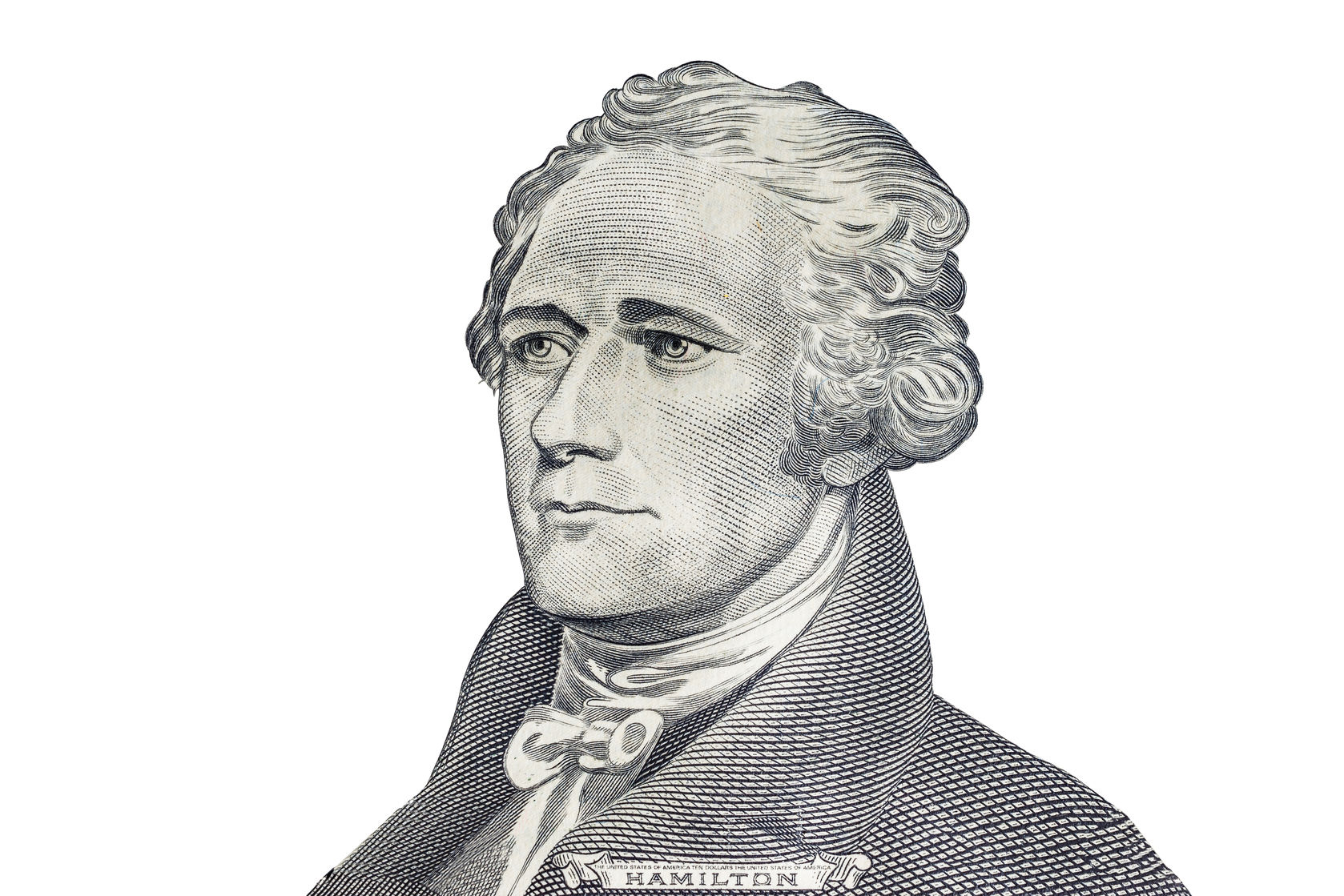

Until the end of the nineteenth century, American foreign policy essentially followed the guidelines laid down by George Washington, in his Farewell Address to the American people: “The great rule of conduct for us in regard to foreign nations is—in extending our commercial relations—to have with them as little political connection as possible.”

The purpose of Washington’s admonition against entanglements with foreign powers was to minimize the chance of war. James Madison, the father of the Constitution, expressed this understanding when he wrote:

Of all enemies to public liberty, war is, perhaps, the most to be dreaded, because it comprises and develops the germ of every other. War is the parent of armies; from these proceed debts and taxes; and armies, and debts, and taxes are the known instruments for bringing the many under the domination of the few.

History taught that republics that engaged in frequent wars eventually lost their character as free states. Hence, war was to be undertaken only in defense of our nation against attack. The system of government that the Founders were bequeathing to us—with its division of powers, checks and balances, and power concentrated in the states rather than the federal government—depended on peace as the normal condition of our society.

This was the position not only of Washington and Madison, but of John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and the other men who presided over the birth of the United States. For over a century, it was adhered to and elaborated by our leading statesmen. It could be called neutrality, or nonintervention, or America first, or, as its modern enemies dubbed it, isolationism. The great revisionist historian Charles A. Beard called it Continental Americanism. This is how Beard defined it in A Foreign Policy for America, published in 1940:

[It is] a concentration of interest on the continental domain and on building here a civilization in many respects peculiar to American life and the potentials of the American heritage. In concrete terms, the words mean non-intervention in the controversies and wars of Europe and Asia and resistance to the intrusion of European or Asiatic powers, systems, and imperial ambitions into the western hemisphere [as threatening to our security].

An important implication of this principle was that, while we honored the struggle for freedom of other peoples, we would not become a knight-errant, spreading our ideals throughout the world by force of arms. John Quincy Adams, secretary of state to James Monroe and later himself president of the United States, declared, in 1821:

Wherever the standard of freedom and independence has been or shall be unfurled, there will be America’s heart, her benedictions, and her prayers. But she does not go abroad in search of monsters to destroy. She is the well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all. She is the champion and vindicator only of her own.

John Quincy Adams was the real architect of what became known as the Monroe Doctrine. In order to assure our security, we advised European powers to refrain from interfering in the Western Hemisphere. In return, however, we promised not to interfere in the affairs of Europe. The implied contract was broken and the Monroe Doctrine annulled in the early twentieth century by Theodore Roosevelt and, above all, Woodrow Wilson.

This noninterventionist America, devoted to solving its own problems and developing its own civilization, became the wonder of the world. The eyes and hopes of freedom-loving peoples were turned to the Great Republic of the West.

But sometimes the leaders of peoples fighting for their independence misunderstood the American point of view. This was the case with the Hungarians, who had fought a losing battle against the Habsburg monarchy and its Russian allies. Their cause was championed by many sectors of American public opinion. When the Hungarian patriot Louis Kossuth came to America, he was wildly cheered. He was presented to the president and Congress and hailed by the secretary of state, Daniel Webster. But they all refused to help in any concrete way. No public money, no arms, aid, or troops were forthcoming for the Hungarian cause. Kossuth grew bitter and disillusioned. He sought the help of Henry Clay, by then the grand old man of American politics. Clay explained to Kossuth why the American leaders had acted as they did: By giving official support to the Hungarian cause, we would have abandoned “our ancient policy of amity and non-intervention.” Clay explained:

By the policy to which we have adhered since the days of Washington. . . we have done more for the cause of liberty in the world than arms could effect; we have shown to other nations the way to greatness and happiness. . . . Far better is it for ourselves, for Hungary, and the cause of liberty, that, adhering to our pacific system and avoiding the distant wars of Europe, we should keep our lamp burning brightly on this western shore, as a light to all nations, than to hazard its utter extinction amid the ruins of fallen and falling republics in Europe.

Similarly, in 1863, when Russia crushed a Polish revolt with great brutality, the French Emperor invited us to join in a protest to the Tsar. Lincoln’s secretary of state, William Seward, replied, defending “our policy of non-intervention—straight, absolute, and peculiar as it may seem to other nations”:

The American people must be content to recommend the cause of human progress by the wisdom with which they should exercise the powers of self-government, forbearing at all times, and in every way, from foreign alliances, intervention, and interference.

This policy by no means entailed the “isolation” of the United States. Throughout these decades, trade and cultural exchange flourished, as American civilization progressed and we became an economic powerhouse. The only thing that was prohibited was the kind of intervention in foreign affairs that was likely to embroil us in war.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, however, a different philosophy began to emerge. In Europe, the free-trade and noninterventionist ideas of the classical liberals were fading; more and more, the European states went in for imperialism. The establishment of colonies and coaling stations around the globe—and the creation of vast armies and navies to occupy and garrison them—became the order of the day.

In the United States, this imperialism found an echo in the political class. In 1890, Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan, of the Naval War College, published The Influence of Sea Power Upon History . Soon translated into many foreign languages, it was used by imperialists in Britain, Germany, Japan, and elsewhere to intensify the naval arms race and the scramble for colonies. In America, a young politician named Theodore Roosevelt made it his bible.

The great Democratic President Grover Cleveland—strict constitutionalist and champion of the gold standard, free trade, and laissez-faire—held out against the rising tide. But ideas of a “manifest destiny” for America transcending the continent and stretching out to the whole world were taking over the Republican Party. Roosevelt, Mahan, Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, John Hay, and others formed a cabal imbued with the new, proudly imperialist vision. They called their program “the large policy.”

To them, America up until then had been too small. As Roosevelt declared, “The trouble with our nation is that we incline to fall into mere animal sloth and ease.” Americans lacked the will to plunge into the bracing current of world politics, to court great dangers, and do great deeds. Instead, they were mired in their own petty and parochial affairs—their families, their work, their communities, their churches, and schools. In spite of themselves, the American people would have to be dragged to greatness by their leaders.

Often, the imperialists put their case in terms of the allegedly urgent need to find foreign markets and capital outlets for American business. But this was a propaganda ploy, and American business itself was largely skeptical of this appeal. Charles Beard, no great friend of capitalists, wrote, “Loyalty to the facts of the historical record must ascribe the idea of imperial expansion mainly to naval officers and politicians rather than to businessmen.” For instance, as the imperialist frenzy spread and began to converge on hostility to Spain and Spanish policy in Cuba, a Boston stockbroker voiced the views of many of his class when he complained to Senator Lodge that what businessmen really wanted was “peace and quiet.” He added, with amazing prescience, “If we attempt to regulate the affairs of the whole world we will be in hot water from now until the end of time.”

In 1896, the imperialists got their chance, when William McKinley replaced Grover Cleveland as president. McKinley has the reputation of an “archconservative.” In reality, as Walter Karp wrote in his brilliant work The Politics of War, “What McKinley envisioned for the American Republic was a genuine new order of things, a modern centralized order, elitist in every way, and profoundly alien to the spirit of the Republic.“ The key to McKinley’s transformation of America would be the “large policy.” McKinley made Hay his secretary of state and brought Theodore Roosevelt into the Navy Department. And a golden opportunity presented itself: the plight of Spain in its rebellious colony Cuba.

The year 1898 was a landmark in American history. It was the year America went to war with Spain—our first engagement with a foreign enemy in the dawning age of modern warfare. Aside from a few scant periods of retrenchment, we have been embroiled in foreign politics ever since.

Starting in the 1880s, a group of Cubans agitated for independence from Spain. Like many revolutionaries before and after, they had little real support among the mass of the population. Thus they resorted to terrorist tactics—devastating the countryside, dynamiting railroads, and killing those who stood in their way. The Spanish authorities responded with harsh countermeasures.

Some American investors in Cuba grew restive, but the real forces pushing America towards intervention were not a handful of sugarcane planters. The slogans the rebels used—“freedom” and “independence”—resonated with many Americans, who knew nothing of the real circumstances in Cuba. Also playing a part was the “black legend”—the stereotype of the Spaniards as blood-thirsty despots that Americans had inherited from their English forebears. It was easy for Americans to believe the stories peddled by the insurgents, especially when the “yellow” press discovered that whipping up hysteria over largely concocted Spanish “atrocities”—while keeping quiet about those committed by the rebels—sold papers.

Politicians on the lookout for publicity and popular favor saw a gold mine in the Cuban issue. Soon the American government was directing notes to Spain expressing its “concern” over “events” in Cuba. In fact, the “events[ were merely the tactics colonial powers typically used in fighting a guerrilla war. As bad or worse was being done by Britain, France, Germany, and others all over the globe in that age of imperialism. Spain, aware of the immense superiority of American forces, responded to the interference from Washington by attempts at appeasement, while trying to preserve the shreds of its dignity as an ancient imperial power.

When William McKinley became president in 1897, he was already planning to expand America’s role in the world. Spain’s Cuban troubles provided the perfect opportunity. Publicly, McKinley declared: “We want no wars of conquest; we must avoid the temptation of territorial aggression.” But within the U. S. government, the influential cabal that was seeking war and expansion knew they had found their man. Senator Henry Cabot Lodge wrote to Theodore Roosevelt, now at the Navy Department, “Unless I am profoundly mistaken, the Administration is now committed to the large policy we both desire.” This “large policy,” also supported by Secretary of State John Hay and other key figures, aimed at breaking decisively with our tradition of nonintervention and neutrality in foreign affairs. The United States would at last assume its “global responsibilities,” and join the other great powers in the scramble for territory around the world.

The leaders of the war party camouflaged their plans by speaking of the need to procure markets for American industry, and were even able to convince a few business leaders to parrot their line. But in reality none of this clique of haughty patricians—“old money,” for the most part—had any strong interest in business, or even much respect for it, except as the source of national strength. Like similar cliques in Britain, Germany, Russia, and elsewhere at the time, their aim was the enhancement of the power and glory of their state.

In order to escalate the pressure on Spain, the battleship U.S.S. Maine was dispatched to Havana’s harbor. On the night of February 15, the Maine exploded, killing 252 men. Suspicion immediately focused on the Spaniards—although they had the least to gain from the destruction of the Maine. It was much more likely that the boilers had blown up—or even that the rebels themselves had mined the ship, to draw America into a war the rebels could not win on their own. The press screamed for vengeance against perfidious Spain, and interventionist politicians believed their hour had come.

McKinley, anxious to preserve his image as a cautious statesman, bided his time. He pressed Spain to stop fighting the rebels and start negotiating with them for Cuban independence, hinting broadly that the alternative was war. The Spaniards, averse to simply handing the island over to a terrorist junta, were willing to grant autonomy. Finally, desperate to avoid war with America, Madrid did proclaim an armistice—a stunning concession for one sovereign state to make at the bidding of another.

But this was not enough for McKinley, who had his eyes set on bagging a few of Spain’s remaining possessions. On April 11, he delivered his war message to Congress, carefully omitting to mention the concession of an armistice. A week later, Congress passed the war resolution McKinley wanted.

In the Far East, Commodore George Dewey was given the go-ahead to carry out a prearranged plan: proceed to the Phillipines and secure control of Manila’s harbor. This he did, bringing along Emilio Aguinaldo and his Filipino independence fighters. In the Caribbean, American forces quickly subdued the Spaniards in Cuba, and then, after Spain sued for peace, went on to take over Puerto Rico, as well. In three months, the fighting was over. It had been, as Secretary of State John Hay famously put it, “a splendid little war.”

The quick U. S. trouncing of decrepit Spain filled the American public with euphoria. It was a victory, people believed, for American ideals and the American way of life against an Old World tyranny. Our triumphant arms would guarantee Cuba a free and democratic future.

Against this tidal wave of public elation, one man spoke out. He was William Graham Sumner-Yale professor, famed social scientist, and tireless fighter for private enterprise, free trade, and the gold standard. Now he was about to enter his hardest fight of all.

On January 16, 1899, Sumner addressed an overflow crowd of the Yale Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa. He knew that the assembled Yalies and the rest of the audience were brimming with patriotic pride. With studied irony, Sumner titled his talk “The Conquest of the United States by Spain.” (It is contained in the Liberty Press edition of On Liberty, Society, and Politics: The Essential Essays of William Graham Sumner.)

Sumner threw down the gauntlet:

We have beaten Spain in a military conflict, but we are submitting to be conquered by her on the field of ideas and policies. Expansionism and imperialism are nothing but the old philosophies of national prosperity which have brought Spain to where she is now.

Sumner proceeded to outline the original vision of America cherished by the Founding Fathers, radically different from what prevailed among the nations of Europe:

They would have no court and no pomp; nor orders, or ribbons, or decorations, or titles. They would have no public debt. There was to be no grand diplomacy, because they intended to mind their own business, and not be involved in any of the intrigues to which European statesmen were accustomed. There was to be no balance of power and no “reason of state” to cost the life and happiness of citizens.

This had been the American idea, our signature as a nation: “It is by virtue of this conception of a commonwealth that the United States has stood for something unique and grand in the history of mankind, and that its people have been happy.”

The system the Founders bequeathed to us, Sumner held, was a delicate one, providing for the division and balance of powers and aimed at keeping government small and local. It was no accident that Washington, Jefferson, and the others who created the republic issued clear warnings against “foreign entanglements.” A policy of foreign adventurism would, in the nature of things, bend and twist and ultimately shatter our original system. As foreign affairs became more important, power would shift from communities and states to the federal government, and, within that, from Congress to the president. An ever-busy foreign policy could only be carried out by the president, often without the knowledge of the people. Thus, the American system, based on local government, states’ rights, and Congress as the voice of the people on the national level, would more and more give way to a bloated bureaucracy headed by an imperial presidency.

But now, with the war against Spain and the philosophy behind it, we were letting ourselves in for the old European way, Sumner declared—“war, debt, taxation, diplomacy, a grand governmental system, pomp, glory, a big army and navy, lavish expenditures, political jobbery—in a word, imperialism.”

Already, it seems, the global meddlers had come up with what was to be their favorite smear word: “isolationist.” And already Sumner had the appropriate retort. The imperialists “warn us against the terrors of ‘isolation,’” he said, but “our ancestors all came here to isolate themselves” from the burdens of the Old World. “When the others are all struggling under debt and taxes, who would not be isolated in the enjoyment of his own earnings for the benefit of his own family?”

In abandoning our own system, there would be, Sumner freely admitted, compensations. Immortal glory is not nothing, as the Spaniards well knew. To be a part, even a pawn, in a mighty enterprise of armies and navies, to identify with great imperial power projected around the world, to see the flag raised on victorious battlefields—many peoples in history thought that game well worth the candle. Only . . . only, it was not the American way. That way had been more modest, more prosaic, parochial, and, yes, middle class . It was based on the idea that we were here to live out our lives, minding our own business, enjoying our liberty and pursuing our happiness in our work, families, churches, and communities. It had been the “small policy.”

There is a logic in human affairs, Sumner the social scientist cautioned—once you make a certain decision, some paths that were open to you before are closed, and you are led, step by step, in a certain direction. America was choosing the path of world power, and Sumner had little hope that his words could change that. Why was he speaking out then? Simply because “this scheme of a republic which our fathers formed was a glorious dream which demands more than a word of respect and affection before it passes away.”

Sumner had to endure a storm of abuse for spoiling the national victory party. But suddenly the imperialists had problems of their own: before they could take control of the Philippines, they had to defeat Aguinaldo and his Filipino insurgents, now fighting for independence from America.

By 1899, the United States was involved in its first war in Asia. Three others were to follow in the course of the next century: against Japan, North Korea and China, and, finally, Viet Nam. But our first Asian war was against the Filipinos.

At the end of the Spanish-American War, we collected Puerto Rico as a colony, set up a protectorate over Cuba, and annexed the Hawaiian Islands. President William McKinley also forced Spain to cede the Philippine Islands. To the American people, McKinley explained that, almost against his will, he had been led to make the decision to annex: “There was nothing left for us to do but to take them all, and educate the Filipinos, and uplift and civilize and christianize them as our fellow-men for whom Christ also died.” McKinley was either unaware of or simply chose not to inform the people that, except for some Muslim tribesmen in the south, the Filipinos were Roman Catholics, and, therefore, by most accounts, already Christians. In reality, the annexation of the Philippines was the centerpiece of the “large policy” pushed by the imperialist cabal to enlist the United States in the ranks of the great powers. To encourage the Americans in their new role, Rudyard Kipling, the British imperialist writer, composed a poem urging them to “take up the White Man’s Burden.”

There was a problem, however. When the war with Spain started, Emilio Aguinaldo, the leader of the Philippine independence movement, had been brought to the islands by Commodore Dewey himself. Aguinaldo had raised an army of Filipino troops who had acquitted themselves well against the Spanish forces. But they had fought side by side with the Americans to gain their independence from Spain, not to change imperial masters. With the Spaniards gone, the Filipinos prepared a constitution for their new country—while McKinley prepared to conquer it. Hostilities broke out in February 1899, and an American army of 60,000 men was sent halfway across the globe to subdue a native people.

Probably a majority of Americans joined in the fun of the faraway war. But thoughtful citizens wondered what this strange adventure would mean for the republic.

To protest the war with Spain, the Anti-Imperialist League had been formed. It included some of the most distinguished figures in politics, business, journalism, and education. Most were also, not by accident, believers in the classical-liberal, laissez-faire vision of American society and staunch advocates of free enterprise, small government, low taxes, and the gold standard. Now the league turned its efforts to ending the war against the Philippines and stopping the annexation of the islands. What was occurring, they warned, was a revolution. While most Americans remained seemingly unaware or unconcerned, the U.S was entering onto the road of imperialism, which, the League declared, “is hostile to liberty and tends towards militarism, an evil from which it is our glory to be free.” The “large policy” of global expansion would mean never-ending war and preparation for war; and that would mean ever-increasing government control and ever-higher taxes.

Carl Schurz, leader of the German-American community, had come here to escape militarism and arbitrary government in his native country. He pointed out the consequences of the new dispensation: “Every American farmer and workingman, when going to his toil, will, like his European brother, have to carry a fully-armed soldier on his back.” Edward Atkinson, who was head of a Boston insurance company as well as a radical libertarian, produced a series of pamphlets, including “The Cost of a National Crime,” detailing the U. S. military oppression of the Filipinos as well as the burgeoning cost of the war to peaceful American taxpayers. E. L. Godkin, editor of The Nation , at the time the country’s leading classical-liberal magazine, accused the imperialists of wanting to make America into “a great nation” in the European style, and thus prove that Washington and Jefferson had been a pair of “old fools.” Andrew Carnegie critiqued the doctrine that annexation of the Philippines was somehow required for American prosperity. And Mark Twain weighed in with sardonic blasts at a marauding American government that was betraying the principles it allegedly upheld. For their pains, the opponents of the war were smeared as contemptible “traitors” by the establishment press, led by The New York Times.

The anti-imperialists gained powerful ammunition for their attacks when letters from American soldiers to their families at home detailed—often with naive pride—the atrocities being committed by U. S. troops. Prisoners were routinely shot, whole villages burned down, civilians, including children, killed in batches of hundreds—all with the knowledge of—and usually under the direction of—commanding officers. Soon the Filipino victims were in the tens of thousands, and the number of American casualties far outnumbered those of the Spanish-American War itself. Americans in the Philippines were conducting themselves worse than the Spaniards ever had in Cuba. People wondered: How did we ever get ourselves into such a mess? The anti-imperialists pointed out that this was how the British were acting in the Sudan, the Italians in Abyssinia, the Germans in Southwest Africa. It was part of the price of empire.

The dirty war went on until, in March 1901, Aguinaldo was captured and the Filipino fighters surrendered. But now America was an Asiatic power, plunged into the maelstrom of the imperialist struggle in the Far East. Secretary of State John Hay proclaimed the “Open Door” policy in China: American diplomatic, political, and, if necessary, military power would be applied to force free trade throughout China. Our advance base in the Philippines and our wide-ranging Chinese policy would obviously entail conflict with powers already there. Already, at the Navy Department, they were beginning to talk of the coming “inevitable” war with Japan.

We began to meddle in world affairs—or, as the imperialists put it, to assume our “global responsibilities” in ways our leaders had studiously avoided before. We took part in international conferences; we dispatched troops to China to join those of the other powers in putting down the Boxer Rebellion of Chinese patriots; we sailed our shining new navy around the world to show that we too had become a world power; and our government became a promoter of overseas investment and foreign trade on a grand scale and at taxpayers’ expense. In Washington, the bureaucracies expanded at the State Department, the Navy Department, and elsewhere, filled with bright young men steeped in the new vision of America’s global destiny. More and more, the American wealth machine was diverted to furnishing the underpinnings of world power.

When McKinley was assassinated in 1901, he was succeed as president by one of the country’s prime imperialists. Theodore Roosevelt was a politician of the new breed through and through. With great insight, H. L. Mencken later compared him with Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany. Both loved big armies and, especially, navies, Mencken wrote, and both believed in strong government both at home and abroad; no one ever heard either of them ever speak of the rights of man, only of the duties of citizens to the state. Interestingly, Teddy Roosevelt was a boyhood hero of a later American president—Lyndon Johnson—who admired his “toughness.”

A good deal of that reputation for “toughness” derived from the Perdicaris affair in 1904. This episode showed for the first time how an instant “success” overseas could be used by a president for his own political advantage. A Republican convention was meeting in Chicago, without much enthusiasm, to renominate Roosevelt for president. Ion Perdicaris was a wealthy merchant living in Morocco. Allegedly an American citizen, he had been seized by a Moroccan chieftain named Raisuli and held for ransom. Roosevelt rushed American warships to Tangiers, and the famous, curt message was telegraphed to the Sultan: “Perdicaris alive or Raisuli dead.”

When the Republican convention heard the news, it went wild with patriotic fervor. The only problem was that the State Department had already informed Roosevelt that Perdicaris was no longer an American citizen, having registered as a Greek subject in Athens for business reasons. Moreover, arrangements had already been made to free him. Roosevelt was aware of all of this; but the political gain from deceiving the public was too tempting. In time, other presidents would learn the same trick of projecting American power overseas simply to give their personal popularity a much-needed boost.

In 1912, Woodrow Wilson was elected president in a three-way election. Wilson was a “progressive,” a leader in the movement that advocated using the full power of government to create “real democracy” at home. But Wilson’s horizons were much broader than the United States. Preaching the gospel of “making the world safe for democracy,” he aimed to extend the progressive creed to the ends of the earth. More than Franklin Roosevelt himself, Woodrow Wilson is the patron saint of the “exporting democracy” clique in America today.

Even before the crisis came, Wilson announced his new revelation:

It is America’s duty and privilege to stand shoulder to shoulder to lift the burdens of mankind in the future and show the paths of freedom to all the world. America is henceforth to stand for the assertion of the right of one nation to serve the other nations of the world.

Soon America had its chance to serve. In 1914, Europe went to war, the bloodiest and costliest war in history up to that time.

The First World War was triggered by the assassination of the Archduke Francis Ferdinand, heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary, in Sarajevo, by a Bosnian Serb. But the war’s twisted roots went back for decades in the dark and complex diplomacy of the great powers. By 1914, Europe was an armed camp, divided into two great opposing blocks: the Triple Entente of France, Russia, and England, and the Triple Alliance of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and a less-than-reliable Italy. All the powers had vast armies and navies, equipped with the latest, most expensive weapons modern technology could produce.

When they heard of the murder of the Archduke (and of his wife Sophie), the Austrians decided to put an end, once and for all, to the Serbian threat to their tottering empire. They felt secure in the support of a powerful Germany. But Serbia was the protégé of Russia and the key to Russia’s designs in the Balkans. And Russia was allied with France, which in turn was linked to Britain by a “cordial understanding,” or Entente Cordiale. In the last weeks of July, halfhearted peace proposals were swept aside, as mutual fear gripped the European leaders and the orders were issued to mobilize the great armies. Ultimatums and declarations of war followed each other in rapid succession. By August 4, 1914, the European powers were at war and their armies were on the march.