Michael Shaw, Randy Simmons, Carl P. Close

Contents

- Introductory Remark by David Theroux

- Carl Close, Co-editor, Re-Thinking Green: Alternatives to Environmental Bureaucracy; Academic Affairs Director, Independent Institute

- Michael Shaw, Founder of Liberty Garden; Co-founder of Freedom 21, Santa Cruz

- Randy T. Simmons, Professor of Political Science at Utah State University; Research Fellow, Independent Institute

- Questions and Answers

David Theroux

President, The Independent Institute

Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. My name is David Theroux, and I want to welcome you to our Independent Policy Forum this evening. It’s a beautiful evening. We’re so glad that you could join us despite the wonderful weather that you could be distracted by.

As you know, we hold regular programs like this on a regular basis. They might be debates, or seminars, or panel discussions, or lectures at our conference center here in Oakland.

Our program this evening is entitled “Bureaucracy vs. the Environment: What Should Be Done?” And this evening, we’re particularly pleased to feature the new book Re-Thinking Green, which is a book that we publish here at the Institute, and I’ll have more to say about that in a minute.

For those of you who are new to the Institute, hopefully you all got a packet of information about our program. The Institute is a nonprofit, academic, public policy research institute. We sponsor studies by different scholars on major issues. We have about 140 research fellows currently who are involved in different projects. You’re welcomed to visit our website, which is at Independent.org and you’ll find a wealth of information on environmental issues and virtually every other issue imaginable.

We also publish many books in addition to the one we’re featuring this evening, and you’re welcome to get information. There’s a catalog in your packet that you’re welcomed to ask us questions about. We also publish a journal called The Independent Review, which is quarterly, and there are copies upstairs, and you’re welcome to sample. And I think you’ll find that quite interesting.

I also want to point out another one of our books, which you’ll find in the catalog, which is called A Poverty of Reason. It’s a look at the issues of sustainable development, economic growth, the precautionary principle, and all of that also relates to this evening’s topic.

Incidentally, for those of you who are not aware, we also produce a weekly e-mail newsletter called The Lighthouse, and that’s complimentary for anyone who wants to receive it. If you do want to receive it, just go to our home page, and you can subscribe or leave us your e-mail address. We’d be happy to send that to you.

Environmental quality has been, as you all know, a major public concern, certainly since the first Earth Day in 1970, but, of course, the issue goes far further back than that. An increasing number of people have become concerned about sort of a maze of environmental bureaucracies that exist, which inhibit decision making and flexibility to deal with complex ecosystems, and the rights of people, and legal disputes, and many other things.

One of the questions is, what can these failures or problems teach us about how best to deal with the realities of environmental issues? How can entrepreneurship, how can individuals, be effective in fostering ways to deal with issues like endangered species, or sensitive habitat, or land use? Issues of all sorts and so forth.

For example, the June 11 issue of the San Francisco Chronicle reported how governments have created millions of conservation refuges worldwide through various wildlife preserves. This is particularly notable, as the article pointed out, in Africa. They’re creating these wildlife preserves while essentially destroying the lives of the people who live there. In other words, in the name of protecting the environment for these people, they’re actually destroying the lives.

Here’s a quote from the journal: “Younger, enlightened conservationists are now willing to admit that wrecking the lives of 10 million or more poor, powerless people has been an enormous mistake, not only a moral, social, philosophical and economic mistake, but an ecological one as well. They’ve learned from bitter experience that national parks and protected areas surrounded by angry, hungry people who describe themselves as, ‘enemies of conservation,’ are generally doomed to fail.”

The lesson here that good intentions are not enough is clear, and this certainly applies to environmental issues. So, instead of bureaucracy and interest group politics, various economists and others have been looking for a while now toward incentives and what’s called economically or market-based approaches to environmental issues, to create positive incentives fostering conservation, and at the same time protecting the rights of people to advance themselves.

So to address these issues, we’re very pleased to have three really excellent speakers, extremely knowledgeable on these issues.

Our first speaker is Carl Close, who is the co-editor of Re-Thinking Green. Carl is the academic affairs director here at the Independent Institute. He’s also the assistant editor of our journal, The Independent Review, and editor of The Lighthouse, the e-mail newsletter I mentioned. He’s also co-editor of another one of our new books, which is called The Challenge of Liberty, which you can also see information in your catalog.

Carl received his B.A. in economics from San Francisco State University and his M.A. in economics from the University of California at Santa Barbara.

Carl Close

Academic Affairs Director, Independent Institute

Like many of you, I grew up with Earth Day, which was recognized every April in my schools. I remember attending a grammar school that had rallies where traveling troubadours would sing songs about preserving the environment. They’d perform funny skits about why you shouldn’t mess around with Mother Nature. And they would get hundreds of us shouting at the top of our lungs very simple but clever slogans that stuck, like “Give a hoot! Don’t pollute!”

On the big trash day each year, we could volunteer which part of the school grounds we could clean up, pick up abandoned newspapers, candy wrappers, and other unsightly litter that had accumulated along the fence surrounding the school in a very windy home town.

I loved playing in a huge gully near my house, a hillside labyrinth made of sandstone and filled with bushes and thistles that stuck to my navy blue sweater and white socks. You couldn’t explore it all in one afternoon. It was huge. It was my Grand Canyon. It was wild with garter snakes, jackrabbits and no adults around. It was my Garden of Eden.

So I was tremendously saddened when it was terraced to make way for new housing. Now here they were, removing me from my Garden of Eden, even though I hadn’t so much as taken a bite from any forbidden fruit, and the only snake I talked to was probably one behind the glass wall at the Academy of Sciences at Golden Gate Park.

Now, years later, I visited a more significant Garden of Eden with my dad, the Galapagos Islands, where I got to see all kinds of fantastic wildlife—Blue-footed boobies—now, those are birds; that’s not a girl group on MTV—and huge tortoises older than Phyllis Diller, and probably more wrinkled.

Marine iguanas spewing salt water out of their heads. Different kinds of finches, each with a uniquely shaped beak that made it better at getting a certain kind of food than other finches. I even had the amazing experience of having a sea lion swim around me while I was snorkeling.

But all was not well in paradise. On one of the islands where there were non-tourists living year round, I saw some boys taunt a donkey and trip it. The donkey fell, squealed, the boys laughed, and my blood boiled.

Much later in life, I scolded a cop for throwing a cigarette butt out of his car window. That probably wasn’t exactly sustainable behavior on my part. Old habits die hard. Even today, if I go hiking with friends—Bill knows this—I don’t like it when someone even throws a biodegradable apple core or banana peel on the trail. Better to throw it out of sight than let it biodegrade. Give a hoot. Don’t pollute.

So I guess I was a child of Earth Day. Not the most zealous of its celebrants, but one comfortable with a least some of its rituals.

So you can imagine my surprise when a few weeks ago I got a call from the founder of Earth Day, Mr. John McConnell. He’d seen our book catalog and said he’s very interested in our work, so I told him about our earlier book written by Wilfred Beckerman. It’s called The Poverty of Reason: Sustainable Development and Economic Growth, and Re-Thinking Green.

And I asked John for his story. Now, John’s seen a lot. He’s 91 years old. In 1939, while managing a plastics manufacturing facility, he started thinking about developing a plastic using walnut shells, and then he started looking into other new uses for waste products, and his interest in ecology grew. He was also interested in promoting peace and justice along with the care of the Earth, and he got involved with all kinds of organizations to promote his vision.

I asked him what was the biggest change he’s seen with respect to the environment, and he told me that he thought as a consequence of Earth Day, people seem much more motivated to learn how to help the environment.

Now, I can’t argue with that, but at the same time, a lot of people believe that awareness hasn’t translated into exceptionally effective, efficient or equitable environmental policies.

A March 2006 Gallup poll asked, “Right now, do you think the quality of the environment in the country as a whole is getting better or getting worse?” Twenty-five percent said getting better, 67 percent said getting worse.

Now, it’s easy to put too much credence in those results for any number of reasons. One is that in response to another Gallup poll question the year before—the question was, “Would you say you are optimistic or pessimistic that we’ll be able to solve or make good progress on our environmental problems in the next 20 years?” 54 percent were optimists, 43 percent were pessimists. So, the people in the poll were short-term pessimists and long-term optimists.

In addition, some of the more easily measured outcomes, such as air quality, we’ve seen significant improvements over the last three or four decades, although such progress isn’t necessarily reflected in public opinion polls.

Now, I wonder how someone like John McConnell would explain something like that. Earth Day has raised the public’s awareness of the environment, but the same public thinks that that awareness hasn’t translated particularly well into public policy. Also, I’d ask if those poll results suggest that the public will push for more attention being paid to environmental policy, and if so, exactly what would that portend? Should we have more of the same types of policies with more enforcement, perhaps, or do we need to rethink our approach to environmental policy? I think if you know the title of my book, you have a clue what I would favor.

You’ve heard that one definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting to get different results. With that in mind, here’re some arguments for rethinking our environmental policies. I’ll start off with some criticisms that come from people or groups that you might expect to be critical of our current environmental approach—for example, small business owners who disproportionately bear the brunt of our environmental regulations.

In an analysis submitted by the Small Business Administration’s Office of Advocacy to a Congressional hearing last year, economist Mark Crain found that in 2004, compliance with EPA regulations on average cost small manufacturers—that is, those with 20 or fewer employees—a whopping $15,747 per worker. And that’s compared to $3,391 per worker for larger manufacturers, those with 500 or more employees. Is the Small Business Administration blowing smoke? In response to these types of criticisms, the EPA last year announced that it would implement 42 regulatory reforms to help reduce compliance costs.

Now, another group you might expect to be dissatisfied with many of our environmental policies might be workers. In a study published in a 1995 issue of the Yale Journal of Regulation, economist James Robinson, currently with U. C. Berkeley’s School of Public Health, found that environmental regulations had accounted for much of the slowdown of U.S. manufacturing productivity growth between 1974 and 1986.

What economists call multi-factor productivity, which is the efficiency of labor, machinery and other inputs working together, had by 1986 fallen by about 11.4 percent short of where it would have been had there not been EPA regulations. And this, he says, apparently contributed to a three-decades-long decline in real weekly wages, that is, what workers took home in inflation-adjusted dollars. And that slowdown occurred up until the computer industry boom that began in the 1990s, which helped raise productivity across the board, but particularly in industries most closely tied to information technology.

Now, those are the kinds of criticisms you might expect to hear. Right? Criticisms that maybe an economist might find interesting to investigate. We’ve all heard that accountants and economists are supposedly foolish enough to know the price of everything and the value of nothing, so some of you might say, “Well, what matters isn’t so much the cost of our environmental policies. Everything has costs. It’s that those costs are necessary if we want clean air, clean water, vibrant ecosystems with abundant biodiversity, and other environmental amenities that support both a healthy human population and a healthy planet.”

So let’s consider some of the criticisms of our environmental policies and environmental thinking in general by some individuals who are more closely identified with the environmental movement.

For example, Patrick Moore, who helped found Greenpeace in 1971. He has some very interesting things to say about the environmental movement that he helped shape. “In its early years, Greenpeace,” Moore said—has lots of praise for it. He said, “We sailed the seas saving whales, protesting nuclear testing and nuclear dumping, halting supertankers, saving baby seals, preventing toxic waste discharge, and interfering with net drifts. These were heady times with countless moments of excitement, danger, frustration and victory. Looking back, it’s hard to believe we accomplished so much as we raised public awareness about all things environmental.”

Now, among other adventures or misadventures, you might remember that Greenpeace in 1985, their first Rainbow Warrior ship—they had other ships later on with the same name—was sunk by French commandos in a New Zealand harbor, resulting in the accidental death of photographer Fernando Periera. Moore left Greenpeace a year later, stating his increasing discomfort with Greenpeace’s increasingly confrontational tactics, as he himself came to favor the politics of consensus.

Moore continues, “Little did I realize at the time how this would bring me into open and direct conflict with a movement I’d helped bring into the world. I now find that many environmental groups have drifted into self-serving cliques of narrow vision and rigid ideology. At the same time that business and government are embracing public participation and inclusiveness, many environmentalists are showing signs of elitism, left-wingism and downright ego fascism. The once politically centrist, science-based vision of environmentalism has been largely replaced with extremist rhetoric. Science and logic have been abandoned and the movement is often used to promote causes such as class struggle and anti-corporatism. The public is left trying to figure out what is reasonable and what is not.”

Now some activists call Patrick Moore a sellout. But rather than rush to judgment, let’s consider another criticism of contemporary environmental thinking, or more specifically, environmental policy. This comes from New York Law School professor David Schoenbrod, one of the cofounders of the Natural Resources Defense Council. Schoenbrod was with NRDC from its inception, and in his first case with the NRDC, he sued the EPA for “failing to protect young children from gasoline in lead.” “The agency,” he explains in his book, Saving our Environment from Washington, “was politically at risk from the get-go.”

What he does is paint a picture of the EPA as Congress’ easy way out. Congress created the EPA, in part, to assuage pressures from Detroit. “From 1963 to 1968, the number of states with air pollution laws went from 16 to 46.” This I’m quoting Schoenbrod again. “The burdens imposed varied greatly and were small by modern standards, but they were enough to prompt the auto industry and then the coal mining industry to try to check the state and local responses to grassroots demand. The solution they hit upon was to get Congress to amend the Clean Air Act, to put a national agency in charge of making air pollution laws. The members deliberated. President Nixon established the EPA.

“By the end of the year, the 1970 Clean Air Act endowed it with sweeping new powers to make law. It was a prototype for many subsequent statutes dealing with other kinds of pollution. Through the 1970s, the air pollution laws the EPA made accomplished less than the laws that came directly from Congress, states and localities.

“Today, the air is much cleaner than it was in 1970 and the EPA deserves some of the credit, but it’s simply wrong to think that the EPA imposed environmental protection on a reluctant public.”

He continues, “Major corporations today understand that the EPA provides them with substantial benefits. Its lawmaking is necessarily slow because of procedural requirements imposed by Congress and the courts. The EPA also buffers large corporations from competition from small and emerging businesses. The regulations are expensive to large corporations, but they can be passed on to consumers.”

So, David Schoenbrod and Patrick Moore, both very deep in the environmental movement, have described two kinds of groups that benefit from environmental bureaucracy, or groups that think they benefit most from the current setup, the ideologically driven and the materially driven. Not that there’s anything wrong with those motivations, necessarily. And Schoenbrod’s and Moore’s analysis is complemented by those in our book, Re-Thinking Green.

The book, by the way, is a collection of articles from The Independent Review, our quarterly journal. It represents the best of the environmental articles from the first eight or nine years of the journal’s existence. Most of the articles are written by economists, but don’t let that keep you from reading it. Our aim in The Independent Review is to publish readable scholarship.

In addition to economists, I should add, we also have chapters written by legal scholars, political scientists such as Randy Simmons and Robert Nelson. There’s a professor of geography, law school professor Andrew Morris, a brilliant analyst, former member of the British Parliament, the late Peter Bauer, who was also an economist and a civil servant in Western Africa where he first got his insights that made him such a unique voice in the field of development economics. And there’s even in Re-Thinking Green a professor of philosophy, Loren Lomasky. So it’s filled not with just economists, not that there’s necessarily anything wrong with those kinds of books.

Now, in Re-Thinking Green, we present three basic problems with a wide variety of environmental policies. Let me give you some examples of those and then discuss very briefly their origins and show how they add up to ways that elucidate the observations and experience of Patrick Moore and David Schoenbrod. A lot of the details are going to be provided later on tonight from Randy Simmons and Michael Shaw.

Now, three main problems. These have to do with inefficiency, ineffectiveness and invasiveness.

Regulatory Inefficiency

First, many of our policies are inefficient and they use a lot of resources. I mentioned earlier that one economist argued that the federal command and control of environmental regulations have contributed to a slowdown in economic growth. That sort of analysis is extended in chapter two, written by Craig Marxsen at the University of Nebraska.

What he does is puts this into a wider context. He looks at the development of environmental thought leading up to the EPA and then through the 1970s, the big surge of environmental policy. And what he notes is that a lot of the policies were motivated by the fears associated with books like The Limits to Growth, 1972, published by the Club of Rome. It looked very sophisticated. Lots of computer analyses in the appendix that argued very extreme predictions. We’d run out of natural resources in 20 years. We’ll be choking in pollution. We’ll all die. We’ll certainly have an economic depression, so unless we implement federal command and control policies, our economy is going to suffer and our lives and health and well.

Well, as Marxsen points out, there’s a big irony here, and that is that the policies that that motivated led to a slowdown in economic growth.

Now, here’s another unintended irony, which is that when the economy drags, people start to worry more about jobs than they do about the environment, so too many expensive environmental regulations can be completely counterproductive to promoting environmental ends.

Another example’s the Superfund program. Now this was created partly in response to Love Canal to clean up hazardous waste sites throughout the country. And numerous sites were identified. More than $10 billion was spent. But little heed was given to whether those sites actually posed real health risks to people. A lot of lawyers did well, but that $10 billion would have gone a long way toward addressing more tangible risks such as highway safety. So that’s the first criticism, that our environmental policies are often inefficient.

Regulatory Ineffectiveness

Second, many environmental regulations are ineffective. They don’t work as advertised. Some are outright counterproductive. One example comes from chapter 15 in the book by Randall O’Toole where he discusses so-called smart growth urban planning. Smart growth policies try to make communities more livable and less stressful on the environment by reducing sprawl and increasing urban density, reducing our need to use cars or to live in suburbs.

Now, a lot of these policies sound very appealing to those of us who like vibrant urban areas with lots of mixed-use neighborhoods with attractive areas to walk or bicycle and reliable transit systems. Unfortunately, good intentions don’t guarantee good results.

In Portland, Oregon, for example, city planners were attempting to increase their city’s population by 75 percent and adding 120 miles of rail transit. But population growth of that magnitude, O’Toole points out, would overwhelm any reduction in the rate of automobile usage, causing, in his estimate, three times more traffic congestion, and slower travel times, and more air quality problems than they have now. Rail transit projects typically cost $50 million per mile, but that amount of money could build two-and-a-half miles of four-lane freeway, which has greater carrying capacity than rail transit.

Regulatory Invasiveness

Now, the third basic problem we describe in Re-Thinking Green is that many of our environmental policies are very invasive. I think that’s sort of the differentia of our book, especially the influence of Robert Higgs throughout the editorial process, throughout 10 years of editing that went into the book.

Now, Superfund is certainly one example, but in chapter 17 of the book, Bruce Yandle and Andrew Morris discuss a new strategy by the EPA. It’s called regulation by litigation. And they show how this allowed the agency to extort or extract—maybe that’s more a neutral term—a $1 billion settlement from an industry that by its nature wouldn’t seem terribly appealing to many, yet, it’s one we all use, if only indirectly, and that is the heavy-duty, diesel engine industry.

The EPA had told representatives of the industry that if they use a certain electronic control device on their engines, they’ll be able to meet urban emission standards, and industry complied. Now, you’d think that would get you off the hook if you were working in this industry. But what engine manufacturers did was design engines that met that standard and also focused on getting good mileage on the highway, and the EPA went back to them and claimed that they hadn’t done anything to meet the same emission standards for the highway.

Industry said, “You didn’t tell us we had to meet highway emission standards. We followed your guidelines, and used your approved device, and met urban emission standards. Now we’ve got to meet some other standard you didn’t specify earlier?” But the EPA had the resources to drag this out in court and eventually came up with the settlement.

Now, before there was regulation by litigation, we had traditional regulation by rule making and regulation by negotiation, and the process was very transparent. There was a modicum of certainty for industry and for those who favored stricter standards. The transparency of the regulatory process allowed it to be better monitored by the legislative and the executive branches. Now, that may seem like kind of a legalistic issue that doesn’t really pull on the heartstrings.

Here’s another example of regulatory invasiveness. It has to do with an expansion of the prosecution of environmental crimes. From 1983 to 1985, the Department of Justice indicted 406 corporate defendants and convicted 331 of them, but indicted 1,052 individuals and convicted 732 of them. From 1990 to 1995, the EPA’s budget for prosecuting environmental crimes increased 400 percent. Much of this came from a law known as the Pollution Prosecutions Act of 1990.

Now, it sounds like it might be justifiable, and in many cases it probably is, but do you know what constitutes an environmental crime? If not, you certainly don’t want to be a manager of a wastewater facility. Michael Weitzenhoff and Thomas Mariani were plant managers of a wastewater treatment facility in Honolulu, and over a period of 14 months, they exceeded their permit by discharging 6 percent more waste than allowed. They said they did so because they thought that avoiding a catastrophic failure of a waste treatment plant was authorized under their EPA permit.

But in the court trial, they weren’t permitted to testify to that effect, nor did the EPA have to prove criminal intent. One of them was sentenced to 21 months in prison. The other was sentenced to 33 months. Now, farmers routinely spread not 6 percent of sewer sludge but between one-half and one-third sewer sludge on their grounds, on their farmland, as fertilizer.

The Roots of Government Failure

Now, why do we get policies that are inefficient, ineffective and invasive? Patrick Moore was onto something when he said that, “I believe there is a great deal to be learned by exploring the relationships between ecology and politics. In some ways, politics is the ecology of the human species.” I think he’s on the right track. Just to amend that, I’d say the root cause of environmental failure comes from people not treating political, social and economic systems as seriously as they treat ecological systems.

The Achilles heel of our typical approach to environmental policy, in my opinion, is that we tend to ignore the fact that our political ecology creates different groups working at cross-purposes. That is, the incentives and constraints facing voters, politicians, bureaucrats and special interest groups often act against achieving the common good. Constraints of time, energy, money and knowledge, all of those are virtually insurmountable for anyone. We often don’t know what is the common good, let alone know how to achieve it, let alone have the incentive to push for it.

Voters, for example, are often plagued by the problem of rational ignorance. It doesn’t pay for voters to closely monitor everything that’s going on, so what’s often called voter apathy is actual rational decision to stay home. Politicians, of course, have incentives to appear to do something to solve the problem and to push problems onto other constituents or onto future generations. Government bureaucrats, of course, have incentives to find new problems. And special interest groups, their incentive, often, is to pull the wool over our eyes and come up with a great slogan and call it the public interest.

Now, Robert Higgs, my co-editor, has an excellent book about the role of crisis in creating larger, less-responsive government programs. Military and economic crises often lead to new programs that, after the crisis subsides, still have remnants there. The same is true with regard to environmental crises.

Alternatives to Environmental Bureaucracy

Now, alternatives to environmental bureaucracy. What are we going to do about all this? We’ve got Michael and Randy to fill in more of the details, but I want to just throw out a few broad principles.

First, we want to try to look for low-hanging fruit, that is, policies that are politically easiest to achieve. The Institute’s earlier book, Cutting Green Tape, points out that the largest source for the demand for toxic substances is the federal government, which immunizes itself and its contractors from liability. So that’s something potentially changeable we need to go after if enough of us can get riled up.

Second, you want to align incentives intelligently. For example, in Montana, public forests are managed both by state government and by the U.S. Forest Service. However, the outcome in their different management styles is tremendously different. For example, timber from state forests is sold for revenue for public schools. The forests in Montana that are managed by the feds are managed for the public interest. Now, guess which of these two groups of forests is demonstrably healthier? The one where there are stakeholders who really have a strong incentive to monitor the effectiveness of the program.

So third, end destructive corporate subsidies that encourage misuse of land. Now, I’m trying to go from easier to harder.

Fourth, look for less expensive ways to achieve environmental goals. Instead of command and control policies, employ market-based approaches that allow people to meet environmental goals at a lower cost and also encourage innovation. We have a debate about this in chapters 19 and 20. Economist P.J. Hill and Roy Cordato, two economists taking opposing sides. Both of them have very good points to make. Another reason to buy the book.

Cordato makes a good point that I shouldn’t miss the opportunity to plug, and that is that even market-based proposals where the government sets a goal and industry has some flexibility in determining how to meet it are often flawed, because you still have politics involved in setting the priorities or setting the goals. And far superior, Cordato argues, is relying on stricter enforcement of private property rights, strict liability, the common law of trespass and nuisance and price signals. Under the common law, liability follows a demonstration of harm. Negligence rules may often be superior to rules emphasizing strict liability.

Now, that’s the direction we were going in the 1960s before the federalization of environmental policy. That door was really finally closed in 1981 in the Supreme Court case of Milwaukee v. Illinois. There, the Supreme Court decided that the common law couldn’t be used to establish emission standards that were more stringent than those set by the Clean Water Act. So for more information, you want to check out our earlier book, Cutting Green Tape.

Now, fifth, how about encouraging a diversity of approaches by devolving environmental policy away from the federal level? I think that’s the corollary of my earlier recommendation. Because only by experimentation can we discover a wide variety of ways to improve environmental quality.

Now, sixth, encourage environmental entrepreneurship, and this is where Michael and Randy come in. They’ll provide details on that.

I want to conclude by saying that to improve environmental policy, we need to have the same kind of sense of adventure, the same willingness to try new things and go new places that we saw in John McConnell when he was coming up with the idea for Earth Day, or that little kid who played in the gully. But we can only appreciate those approaches by ditching environmental bureaucracy and recognizing that all of us are part of nature, and that our own processes—social, economic and political—have held us back in the past, but, if we understand how they operate and we rethink our institutions and reform them so that all of them tend to promote our goals of health and material abundance and a beautiful, healthy environment to enjoy as well, we’ll all be better off.

Those are the general outlines, and I look forward to hearing Michael’s presentation now.

David Theroux

President, The Independent Institute

Our next speaker is Michael Shaw, as Carl mentioned. Michael is the proprietor of Liberty Garden, which is a 75-acre private coastal conservation reserve of property near Santa Cruz. He’s also cofounder of Freedom 21 Santa Cruz. He’s president of JM Management and owner of Lockaway Storage. He received his B.A. in political science and his J.D. from Santa Clara University. He’s also practiced as a CPA, as a tax attorney. This is an issue of the journal Ecological Restorations. This is the June 2002 issue, which has an article related to his work, and he’s on the cover of it.

Michael Shaw

Founder of Liberty Garden; Co-founder of Freedom 21, Santa Cruz

Thank you. Abundance ecology or sustainable development. The concepts contrast at their basic core, and what I want to do is explain them both and contrast them one against the other.

Abundance Ecology vs. Sustainable Development

Sustainable development is an attack on private property and individual liberty. Sustainable development is being orchestrated to the political policy process that has been adopted by the federal government and is being implemented by each state and most every county in the country.

I’m going to explain in summary what sustainable development is and how it’s affecting the lives of everyone, particularly from an environmental policy perspective. I’m then going to contrast the concept that we call abundance ecology, which is rooted in the ideals of private property, and use as an example a property that my wife and I own along the coast of Santa Cruz County.

Abundance ecology is the direct relationship between and man and land. That’s the paramount dynamic that defines the nature of abundance ecology. It is for reasons of knowledge and innovation that an improving planet is possible only in a society that respects the ideals of private property. And in summary, and to be very short and to the point, I’m going to define private property as an owner’s determination of the use of property.

Sustainable development, on the other hand, is probably best described from the 1992 Rio conference established by the United Nations. A man named Maurice Strong, who was Secretary General for the Environment and Development section of the United Nations, headmastered the conference, held in Rio in 1992, called the Earth Summit. And there he said that current lifestyles and consumption patterns of the affluent middle class—that would describe everyone in this room, I suspect—involves high meat intake, use of fossil fuels—gasoline—appliances, meaning refrigeration—home and work air conditioning and suburban housing are not sustainable.

Sustainable Development and Agenda 21

The origin of these thoughts are globalist in nature and are promoted firstly and primarily through the United Nations as their Web page clearly announces.

Sustainable development is what they call Agenda 21. The terms are used interchangeably. The Earth Summit, or Agenda 21, was the focus of the 1992 conference in Rio. There was a Rio Plus 5 conference held in 1997. In 2002, they reconvened in Johannesburg, South Africa.

The UN agenda for sustainable development is truly a global-to-local dynamic. In Santa Cruz, the program is straightforwardly called the Local Agenda 21 Program. I sat on that council. The discussion was about how human beings can’t be allowed to further scratch the surface of Mother Earth and the like.

But regardless of the discussion held in the conferences, the outcome was predetermined. The book that concluded these meetings was probably written before the meetings even occurred.

In 1997, the Santa Cruz board of supervisors quietly and unanimously fully endorsed the Local Agenda 21 Program, and it has been being implemented chapter by chapter by local ordinances ever since.

But it’s not just Santa Cruz. The Bay Area Alliance for Sustainable Development covers all the Bay Area counties. In Monterey, it’s called Common Ground and a mission document has been adopted and is being implemented by that board of supervisors. In Orange County, it’s called Orange County Wild. In San Fernando, it’s called Vision 20/20. You’ll see Vision 20/20 documents having been created over the last five years all across the country.

Here in Alameda County, it’s called Measure D, approved by the voters in the year 2000 creating narrow little settlements for development, everything else being off limits for development. My company, Lockaway Storage, is currently involved in litigation knocking down or attacking Measure D here in Alameda County, and I can thankfully say that our as-applied litigation has resulted in the issuance of a permit for the construction of a self-storage facility outside these narrow confines that allow development in this county, and a motion for summary judgment brought by county counsel was denied just this week, so we’re now looking at the damages phase in connection with that litigation.

The United State support for Agenda 21 or sustainable development is clear. In 1992, when sitting in a yacht belonging to Prince Charles off the coast of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, George H. W. Bush signed the implementation documents for the United States to begin its own implementation of the sustainable development, Agenda 21 dynamic. A year later, President Clinton, by executive order, created the President’s Council for Sustainable Development. That included all of the leaders of various environmental groups, and a few business groups were represented, including the chairman of California’s Pacific Gas and Electric and the infamous fellow from Houston named Ken Lay of Enron. Very few people business people were represented, but those that were, I think, were indicative of the kind of policies that have come out of the President’s Council on Sustainable Development through the 1990s.

In 1997, the counties and mayors created the Joint Center for Sustainable Communities, and you’ll see increasingly, and will continue to increasingly see, the term sustainable used by your local elected officials, who when elected, are all trained in the policies of sustainable development.

In the year 2001, the National Governor’s Association endorsed smart growth. Now, smart growth, as I’ll explain in a little more detail a bit later, is the urban side of the sustainable development program.

Sustainable development, according to the United Nations and the federal government, is to meet today’s needs without compromising future generations to meet their own needs. Well, that sounds sweet, but it was lifted right from the 1977 Soviet constitution. And pause for a moment and ask yourself what if America had adopted this back in the late 1800s when Americans were still using whale oil to light their rooms at night so the children might read and grow? If we had said we’re going to save the whale oil in 1880 for people in the 21st century, where would we be? How many people would be educated? How much knowledge and learning could occur when the lights were turned off as the sun set?

It’s the same concept today. We’ve got to save energy processes, fuel, for tomorrow’s generation when human ingenuity, inevitably when set free, as Americans were in the 20th century, will find new sources of energy to keep our lamps lit.

The real purpose of sustainable development is this. Sustainable development is a process by which America is being reorganized around the central principle of state collectivism. It uses the environment as bait while it indoctrinates and prepares our children, through a public school process, to live in a state-run collective.

I like to call sustainable development the concept of shortage ecology. You see, the Endangered Species Act is at the centerpiece of sustainable development, and of course, the Endangered Species Act strictly limits human action. It’s predicated on international treaties and it is rooted in what’s called the precautionary principle.

The precautionary principle holds that anything you do, you must first be able to illustrate that it will cause no harm. There’s no trial. There can be no error. Because if you do something that is presumed then to cause harm, you’ve engaged in criminal activity. It reminds me of the Central Valley farmer who had a fire advancing toward his house, so he plowed out in front of his home. Well, he’s in jail today because he harmed the habitat of an endangered rat that was presumed to be living in his front yard.

You see, the Endangered Species Act puts government in control of plants, animals, and natural resources, and when you put the government in charge of sand, we’d have less sand. We certainly have less of all things good when the government takes its charge.

The Wildlands Project

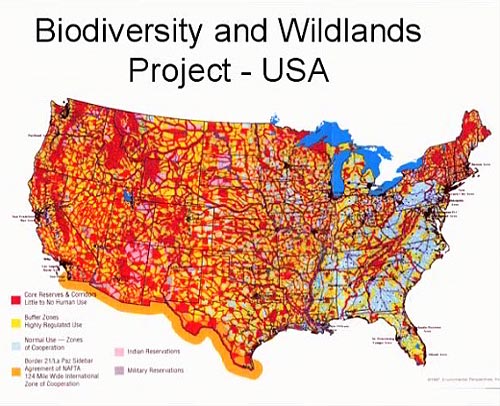

Sustainable development has two basic action plans. The first is the so-called Wildlands Project. Now, the Wildlands Project is designed to eliminate human presence on over 50 percent of the American landscape, and it heavily controls all activity on most of the balance of the remaining land.

This is a map of the Wildlands Project.

It was prepared in 1994 by Dr. Michael Coffman, who, working with others, got information out of Geneva necessary to put this map together. Merely hours before the adoption by the U.S. Senate of this Wildlands proposal, he spread this map to the United States senators, who then did not even bring the issue up for vote. That was the good news. The bad new is that the Wildlands Project has been implemented by federal and state agencies ever since that time.

Now, what this map show is the red areas are those that are wildland areas. The wildland areas are off limits to human beings for either resource extraction or recreation. Roads in the wildlands area are to be demolished. Clinton took a large step forward in his last months in office by eliminating many roads that exist in the red areas on this map.

The orange areas are the areas of massive government control. All activities in the buffer zones, the orange areas, are to be under massive governmental regulation. The black dots that you see are where all human beings are to be. These are the smart growth zones. The Bay Area is beginning to be known by its citizens, even, as being a smart growth hotbed.

Smart growth is the dense human settlement subject to increasing controls on how we live and increasing restrictions on our mobility. Those of you who remember the last election cycle ought to be able to identify easily with the increasing restrictions on our mobility.

This county, Alameda County, passed a $2 billion bond, transportation bond, in the year 2004. Now, if you read the details of the Alameda County’s transportation bonds in 2004, you’ll find that almost all of the money goes to bicycle trails and rail lines. Sure, there was a study that made a lot of press—it wasn’t always disclosed as a study—for the widening of the Caldecott Tunnel. But there’s no funds in those bond measurements for the actual widening. It’s only to study the widening of the necessarily widened tunnel.

The federal government is dead set into the middle of this dynamic. The Bush One presidency, followed by Clinton have taken all the steps necessary to administer sustainable development policies in the United States. All federal agencies have this as a centerpiece. This is from the United States Department of Agriculture Website, and you can see they’re not at all shy about proclaiming their allegiance to sustainable development.

You’ll find that the American Farm Bureau is the United Nations-accredited non-governmental organization, which is why in so many counties, like my own, the Farm Bureau is not coming to the aid of farmers as their lands become subject to the Wildlands dynamic for centralizing control over their farmland. In our county, the farmers have to pay on their own water an extraction fee that will, within a number of years, cause them all to simply go out of business. And it’s not as though there’s a shortage of water coming down from the Santa Cruz Mountains into the broad aquifers of the Paro Valley, but the agencies charged with the implementation of sustainable development tell you otherwise without any evidence. Pass massive taxes and the farmers are in increasing trouble.

But it’s not just local agencies. Americans are increasingly being affected by international NGOs like this one, ICLEI, the International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives. Now, ICLEI, for this hemisphere, is centered, headquartered, in Toronto, Canada. It has one office in the United States. It’s in Berkeley, here in Alameda County.

The purpose of ICLEI is to coordinate with counties around the country. And this Website is from 1997. Today, ICLEI has coordinated with nearly every county in America for purposes of implementing sustainable development. You have to really pull teeth to get your local elected officials to acknowledge that they are in fact coordinating with the ICLEI manipulators who are seeking the implementation of sustainable development policies in your county.

Let me return to the idea of abundance ecology. The practice of abundance ecology is this. The release of the potential productivity and diversity of a landscape, in order to do that, an owner must be free to engage in a rigorous program of disturbance, and he must be free to pursue a reasoned and creative process of trial and error. There’s nothing particularly original about that. That’s been the dynamic in America for 230 years.

But today it’s under extreme pressure from the sustainable development operatives that exist in every community across this country. The process of abundance ecology would be suited to the choice of each individual landowner and the uniqueness of each property.

Abundance Ecology, Property Rights, and Liberty Garden

As David said, the project that we call Liberty Garden on the coast of Santa Cruz was covered in a sustainable development international journal put out by the University of Wisconsin called Ecological Restoration. How it is that we got to the cover of that magazine with a very straightforward analysis of the kinds of things I’m talking about tonight is still beyond me, but it gave me great pleasure then, and it continues to this day.

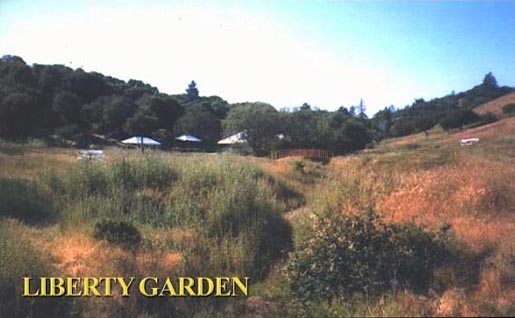

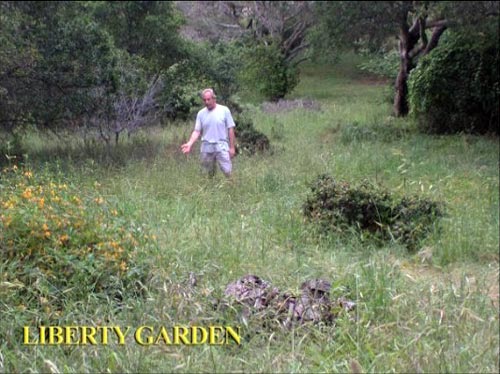

This is Liberty Garden, a picture in 1985 when we bought the property.

I remember the day well because it’s the day that my wife and I got married. And what you’re seeing here is property—the picture’s taken in the springtime—that you couldn’t walk through without plastic pants, because the thistles and the burrs from the European grasses that grew there and supported the cows for decades before this are not the kind of thing that a human being wants to walk through. It’s very inhospitable.

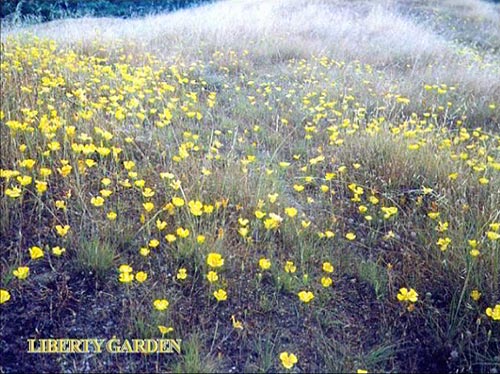

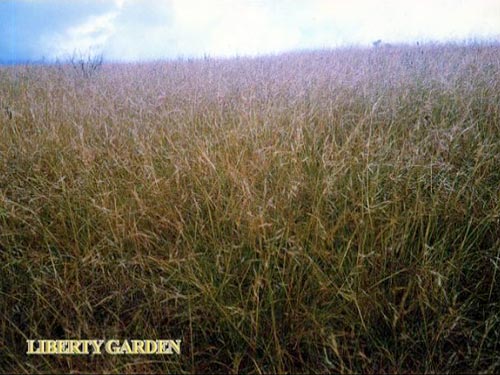

Now, that circled area is of the next picture taken 20 years later in the springtime.

Without planting a single plant or throwing a single seed, but simply by managing the seed bank, we were able to turn that landscape of 100 percent European plants—oh, sure, there was a little poison oak thrown in down in the valley even—into a 100 percent native plant oasis. These are all native grasses and native sedges and native wildflowers.

We conducted that process by just good old-fashioned sweat effort, an idea that the Department of the Interior hasn’t thought of yet.

People were paid to do the work. We knew what we wanted to do. We didn’t quite know how to do it, but it became simpler and simpler. It was just a matter of common sense land management and what we call seed bank management.

I’m going to take you on a little travel through Liberty Garden. This again is another picture taken on my wedding day in 1985.

In the foreground you can see the thistles. You wouldn’t want to come close to touching those. And a dried creek bed, dried even as early as May.

And here it is in December of the year 2003.

The plants and the grasses to the side are all native grasses, predominantly a plant called danthonia, which is the longest-lived grass plant in the world. Each plant can live somewhere between 300 and 1,000 years. And the plants don’t exist, you don’t see them very often, but you do at Liberty Garden, a true oasis of indigenous plant landscape along the coast of California.

It’s not just human beings that enjoy the landscape. All kinds of birds and insects, and not such an unusual animal, but the ducks have taken up residence.

And now probably 20 to 30 are spawned each year, baby ducks make it to maturity and come back the following year.

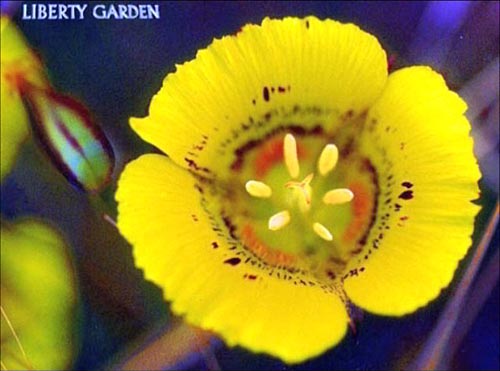

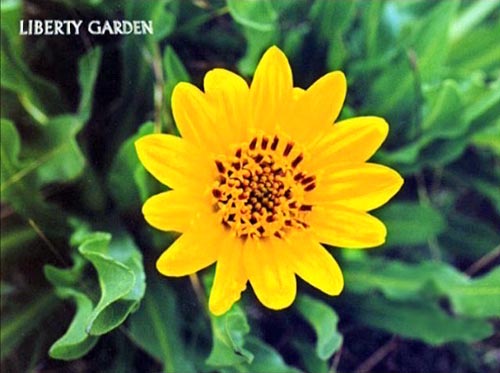

This is my favorite flower growing at Liberty Garden called mariposa lily.

They didn’t exist in 1985 when we bought the property, but today they dot the hillsides along Highway 1 with a prolificness that’s simply unmatched.

The native plant people are—their jaws drop when they come to our property, because you don’t see the kind of native plant dynamic on these government-directed, government-managed lands as you do at Liberty Garden.

Again, a picture from 1985, the entrance to Liberty Garden.

This is an area at that time of year you certainly wouldn’t want to walk through unless you were covered in plastic. And this is what it looked like in the spring of last year.

All native grasses with little wildflowers growing underneath them all. I’m walking through this field in shorts and tennis shoes with socks with nary a burr attached to me, something you couldn’t have done 20 years earlier.

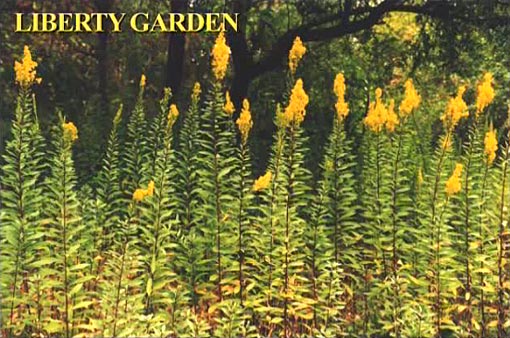

This is a field up on a hillside of what’s called purple needle grass,

Sort of the state grass, I think the legislature dubbed it here recently. And you can search the state to find a few examples of it, but at Liberty Garden, with the process of mowing and other plant management activities, there are solid fields of these that are interspersed only with certain native flowers, like the one you see here.

This is one of my favorite flowers.

It took many years of management before this began to show, and now we probably get a hundred of these blooms scattered all over the property. It’s called a rain orchid. It is an orchid plant and they’re known to grow in California. It is a California native, but they probably don’t grow with per capita rate anywhere in the state as they do at Liberty Garden.

Here’s back to the mariposa lily.

It’s not just human beings who like it, but, you know, it’s the insects that sometimes give me the big thrill on a hike someday when you see insects you’ve never seen before, including butterflies like this one.

This is Indian paintbrush.

You’ll see that down at Big Sur and other places, but this particular area was thick with poison oak. You couldn’t walk in. Nothing could compete with the poison oak other than an oak tree, and after clearing the poison oak, all kinds of indigenous plants began to pop up, like the red Indian paintbrush.

Goldenrod that follows the same example, former poison oak land.

The poison oak was 30 to 40 feet tall. It grew to the top of the oak trees. Nothing could penetrate this poison oak unless it was the size of a packrat or something smaller than that.

I like this little plant.

It grows out along the hill along Highway 1. The native plant experts tell me they’ve never seen them grow this far north in California, but this August, there’ll probably be 300 or more of this lovely little bulb flower growing along Highway 1.

And here’s a California daisy that now grows throughout the property.

And a mule’s ear, which spots, again, the grassland hillside.

And here’s a field of lupine.

At one time, this was all pasture grass. You know, Spanish oats grew four feet tall and by this time of year, there are just little stingers on if they haven’t been eaten by cows or something else. And that’s all been removed. Seed banks have been virtually eliminated and wide fields of this lupine begin to grow.

I’m going to read a quote from the magazine that David showed, Ecological Restoration, quoting me at the end of that article when I said, “Because of the Endangered Species Act, what developer or landowner would want to purchase land and do what we are doing? Disincentives preclude innovation. It’s no wonder that no one else is following a commonsense approach that brings success. That approach is simple. It’s control the weeds, manage the native plants, and manage the hydrology.”

Those are the things we’ve done at Liberty Garden, and those are the things that no one working under the confines of the Endangered Species Act—which we violated for 20 years—has been able to achieve. The ESA is counterproductive to its stated purposes, and that’s the core of what Liberty Garden is intended to prove.

Liberty Garden is zoned for 30 houses. In 20 years, I bought the house in order to raise my little children—they’re now in their 30s—on that land, but we can’t get a permit to do anything. So the reality is that under the Endangered Species Act, the more successful you are, the more you’re punished. It’s why the act must be, in my opinion, repealed. It has led to a society where the landowners process is to shoot, shovel and shut up. Now, we’ve taken the opposite approach, and we get punished for it.

The Endangered Species Act is reliant upon application of the precautionary principle, which prevents human beings from taking the kinds of actions that result in the results of Liberty Garden.

Moving back away from Liberty Garden and back to the concept of sustainable development. Those who are familiar with sustainable development know that it has an emblem, and that emblem is three interconnected circles. Each of the circles represents one of the so-called three E’s.

The Three E’s of Sustainable Development

The first E is equity. Rooted deeply in Communist principles, equity feeds into the second E, which is economy. Public-private partnerships. We used to call it fascism.

You say, well, Americans aren’t going to accept a Communist system of equity and a fascist system of economics. I mean, we have some sense of understanding about history, even if we went to public schools. But you bring in the third E from the top, the environment, and Americans have fallen for the biggest rip off in all of human history.

This is the emblem of sustainable development.

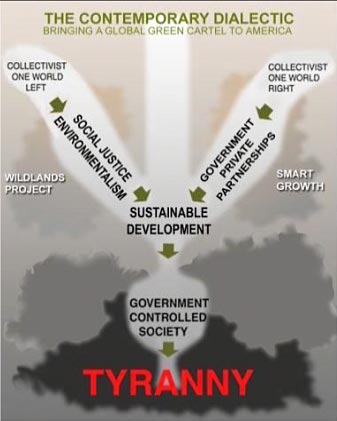

In this short time, I’ve attempted to show you what it really means and where it really comes from. You see, there’s a manufactured dialectic behind sustainable development. You’ve got the right wing with public-private partnerships. We used to call it fascism, but the modern term is public-partnership. And from the left side, we’ve got environmentalism and social justice, you know, the Communist system of government control.

Bring the right together with the left on that basis—I always see Bill Clinton and George Bush Sr. walking arm in arm these days—and you’ve got sustainable development. What it is, is a government-controlled economy which results in tyranny. We’ve moved a long ways down this road.

I don’t think it’s irreversible, but recognition of what sustainable development is all about, understanding that it is in your town, it is in your county—and I could say that to any American anywhere. It has pervaded all things political.

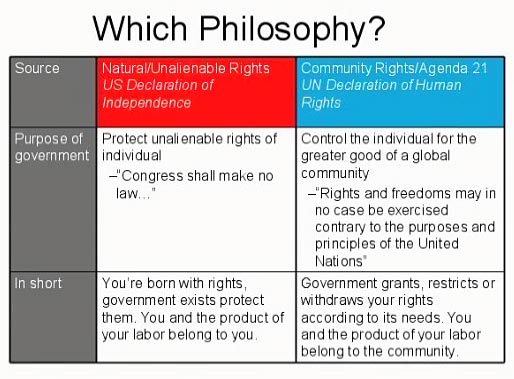

It leads us to this question. Which philosophy do we want to leave for our children?

Do we want a society based upon the natural and unalienable right, the philosophy that was predicated upon the Declaration of Independence? Or do we want community rights and Agenda 21, founded on the principles laid out in the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights?

Now, ask ourselves, what is the purpose of government? For this crowd, that’s an easy question to pose and to answer. But for the average American, confusion is existing and we’ve got to become very proactive in explaining to our neighborhoods and to our communities at large what the dynamic behind sustainable development is. The purpose of government under our traditional system is to protect the individual and unalienable rights of each person. Congress shall make no law.

What we’re seeing being replaced, at the direction of both the Democrat and the Republican parties, is an idea where controlling the individual for the greater good of the community is what’s being served. And we see that best expressed in the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights in Article 29, Section III, where it says “the rights and freedoms may be in no case exercised contrary to the purposes and principles of the United Nations.”

Well, who is the man behind the black curtain? It’s not Kofi Annan. So what are those purposes and principles from time to time and how will they affect our lives as independent human beings? That’s the question that I think Americans need to be asking themselves.

In short, under the US model, we’re born with rights. Government exists to protect those rights. You and the product of your labor belong to you. But under the UN Declaration of Human Rights, government grants, restricts or withdraws your rights according to its needs. You and the product of your labor belong to the community.

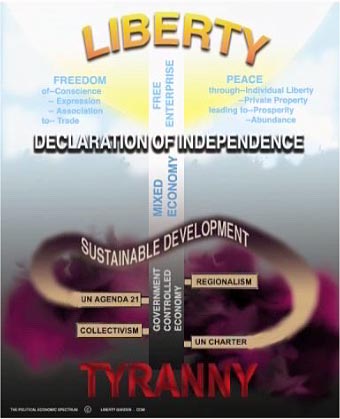

I don’t think the political spectrum runs on a left-right dynamic.

I remember the nuns would teach us that left and right would circle down and combine at the bottom, one to the other. And I remember that every time I see a picture of Bill Clinton and George Bush I walking hand in hand. It’s an up-down, liberty at the top, tyranny at the bottom, and we need to remember what freedom is, and how it’s parents that raised children with a sense of conscience. And it’s that development of conscience that leads us to a system where we’re comfortable exercising our rights to associate and leading to the values of genuine free trade, not international, bogus free trade, but true free trade. And it’s through those freedoms that we obtain peace. Peace comes through private property, and it leads to abundance and prosperity.

Sustainable development puts Americans on a different course. Agenda 21 is about regionalizing government. You’ll see Arnold Schwarzenegger, for instance, three months after he was in office came out with the California Performance Review, 2,500 pages that called for regionalization of everything and the elimination of local school boards and the consolidation of school boards into 10 districts across this state. The state of Massachusetts has eliminated county government as it begins its process of regionalization.

Regionalization is collectivism. It opens the door wide. And as we’ve regionalized and collectivized, we begin to live under the United States Declaration of Human Rights and in a world of tyranny.

Freedom 21 Santa Cruz has products and information, a Website, that will give you a lot more detail on the process of sustainable development, how it’s affecting our communities and what you can do about it. So I recommend you take a look. You can also look at Freedom 21 at LibertyGarden.com, which will identify in more detail what I’ve talked about here tonight from a land management perspective.

I want to thank you and I hope your wariness on sustainable development policies, which come from both major parties in this country quietly and assuredly. Be aware and spread the information to your friends and neighbors. Thank you very much.

David Theroux

President, The Independent Institute

Randy Simmons is the Professor of Political Science at Utah State University, Research Fellow at the Independent Institute, co-author of Beyond Politics: Markets, Welfare, and the Failure of Bureaucracy and a contributing author to Re-Thinking Green: Alternatives to Environmental Bureaucracy. In addition, Randy is working on a new book for us called Political Ecology. Randy.

Randy Simmons

Professor of Political Science at Utah State University; Research Fellow, Independent Institute

A person that David and I know fairly well, Fred Smith, who founded the Competitive Enterprise Institute in Washington, DC, has a very nice line that I think summarizes what Michael just said. Fred’s line is that the road to serfdom is paved with green bricks.

Michael could compare the line in the Declaration of Independence about life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness with the line from the Canadian Charter of peace, order and good government: very different ways of viewing how we might act in our lives.

I’m talking about politics, bureaucracy, courts and the Endangered Species Act. I have to warn you that I am a politician. I’m mayor of my small town of 6,000 people. I’m a bureaucrat because I teach at a state university, and one of the things I teach is Law and Economics, Law and Policy, Law and Politics, so I can talk about the courts. I am just such an example of everything that’s wrong in America.

I’m going to talk specifically about the Endangered Species Act. The politics of the Endangered Species Act, where it was created in 1973 under the Nixon administration. The Congress passed the law and Richard Nixon gleefully signed it because it was such a good thing for the environment. It defined taking an endangered species—prohibited taking an endangered species. And taking means to harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture or collect, or attempt to engage in such conduct.

The problem is that you get that line from the politicians and you move it to the bureaucracy. And the US Fish and Wildlife Service, who manages the Endangered Species Act, said, “harm?” What in the world do we mean by harm?

Harm means, according to the Fish and Wildlife Service, habitat modification on private and public lands. So it includes those things. There’s a host of other things, but one of the important ones is managing or changing habitat on private or public lands. I don’t know why you’re not in jail, Michael, because you really modified that habitat.

And then in the Sweet Home case in 1995, the Supreme Court said that habitat modification is in fact a harm, that Congress meant habitat modification to be included in the definition of harm, and can be regulated under the Endangered Species Act.

The result, according to Michael Bean, who is at Environment Defense—Michael, by the way, is one of the most articulate members of the environmental community in talking about the Endangered Species Act, one of the most honest and careful analysts as well. And he’s been very involved in trying to find ways to improve the Endangered Species Act, which actually almost got him excommunicated from the environmental movement for a while because of the points that Carl made about environmental regulation is often ideologically driven. It often has very little to do with actual outcomes.

And Michael’s actually interested in outcomes, and he said, “A forest landowner harvesting timber, a farmer plowing new ground, or a developer clearing land for a shopping center stood in the same position as a poacher taking aim at a whooping crane.” So, you modify your habitat, you might as well get the shotgun out and shoot what you can, because you’re going to be treated exactly the same.

In the Sweet Home decision, Justice Scalia dissented in this five-to-four vote and said, “The court’s holding imposes unfairness to the point of financial ruin, not just upon the rich, but upon the simplest farmer who finds his land conscripted to national zoological use.” You thought Michael was making this stuff up, didn’t you? And we have Justice Scalia talking about having your land conscripted for national zoological use.

So, what the results of 30 years of Endangered Species Act regulation? Using Scalia’s phrase, does national zoological conscription work?

The Failure of the Endangered Species Act

What we find is that the answer is pretty much no. We have more endangered species than we had when we created the Endangered Species Act. More get added every year. Those that are on the list don’t come off the list. A very tiny number have come off the list.

I don’t know that you can identify government actions as having had any effect on any of them, at least actions taken under the Endangered Species Act. They talk about bald eagles having come back, how wonderful that was. That probably had to do with—this was a government action, actually—banning the use of DDT, but it had nothing to do with the Endangered Species Act. So you have a very small number that’s come off the list. I don’t know that you really can ascribe any of that to the Endangered Species Act.

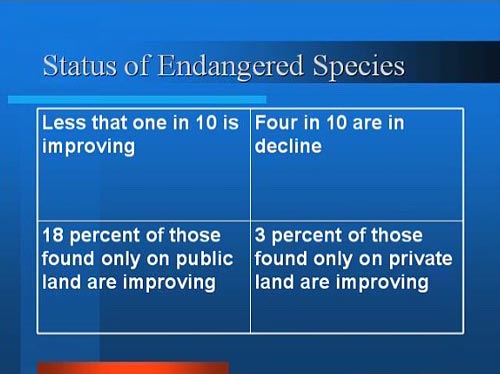

Looking at this, you say, wow, 18 percent of those found only on public lands are improvement, 3 percent of those found only on private land are improvement, less than one-in-10 is improving, four-in-10 are in decline. Wow. That’s not so good. And then we look and we realize that 80 percent of all endangered species are found on private land, places like Liberty Garden.

Now, Michael Bean, again, he’s willing to say the unsayable, which was the reason why he’s sometimes not popular. He says, “Some claim that enforcing the Endangered Species Act has created unintended negative consequences, including antagonizing many of the landowners whose actions will ultimately determine the fate of many species.” Antagonizing landowners.

There’s rising evidence that people will actively manage their land so that there won’t be endangered species. The problem with doing something to attract species is that then, you can’t do the things that you had wanted to do with your land, like maybe build 30 houses. There are severe restrictions placed on the things that you can do, so you better be careful about attracting them.

What a lot of people do in places like Texas is they go out and rent a bush hog. A bush hog is a machine like a lawnmower that you pull behind your tractor and you use it to just wipe everything off your property. If there’s no habitat, there are no species. And then, you can get what the Fish and Wildlife Service calls a bird letter if you’re in an area where there’s an endangered bird, and the bird letter says you have no birds on your property and you have no habitat for them. Therefore, you can develop it.

Now, again, Michael Bean says, it’s not the people who have any malice towards the environment. It’s just that they’re rational. These are the predictable responses to silly regulation. He doesn’t say silly regulation. He says it much more politely here.

The National Association of Homebuilders has a handbook on endangered species, and it has this little suggestion. Well, it’s not really a suggestion, is it? They just say this is one of the things that happen. “Farming, denuding of property, and managing the vegetation in ways that prevent the presence of such species are often employed in areas where ESA conflicts are known to exist.” Not that you should do them.

Environmental Defense quoted a farmer saying, “I cannot afford to let those woodpeckers take over the rest of the property. I’m going to start massive clear cutting.” This is called pre-emptive habitat destruction. Before the red-cockaded woodpeckers come, you cut your trees, because red-cockaded woodpeckers require trees of a certain size, about 50-to-60 years old, so you—and you normally would harvest at 60 to 80 years, so you harvest them at 30 to 40 years. You don’t make as much money, but you make money.

Now, one of the arguments that is often made by people who think that this is so terrible is, well, people can still make money with their trees even if they do have red-cockaded woodpeckers and are managed by the regulations of the Fish and Wildlife Service. For example, they can—these are long-needled pine. They can still rake the needles and sell it for straw. I mean, people do that. It’s just this very tiny part of their income. But they’re still able to do that.

Now, I teach at a university in northern Utah. We get lots of ranch kids from the West. And in my freshmen class, there are always some kids sitting in the back row in baseball hats. Real cowboys don’t wear cowboy hats. They wear baseball hats. And I say, so “What would you do if a wolf or a grizzly showed up on your ranch?” And there’s some giggling in the back, and I call on one of them, and they say, “Well, we’d just shoot, shovel and shut up.” Well, shoveling a hole for a grizzly is a pretty big hole, but they have tractors with front loaders.

It’s just a phrase that is really widely known, and I always have students who get so upset that these other students would say this, because it’s just such an awful thing to be doing. I mean, we ought to be letting wolves run wild and grizzlies, and we ought to be protecting species in all that we do.

Well, maybe we should, but the difference between shoulds and what we do are often very different, especially when it comes to deciding—when the should—the real question is, who should pay? Because right now, the way the Endangered Species Act is set up, people who own property like Liberty Gardens are the people who end up paying if they get an endangered species, and the rest of us say, “Isn’t that nice? Look, he has some endangered plants on that property, and we’re so glad that he’s done it. And we feel so good and so warm knowing that they’re there and we didn’t pay a dime.”

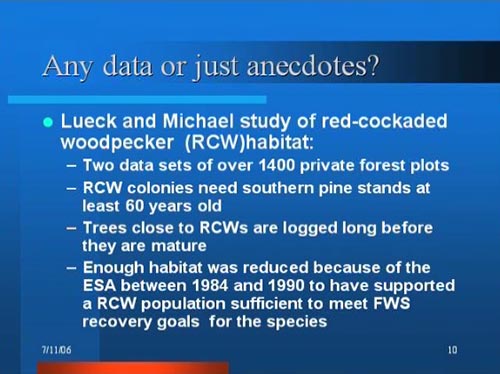

Well, so what about this story of pre-emptive habitat destruction? Are they just stories or are there real data? Well, it turns out there really are data. This is a study about red-cockade woodpeckers done by Dean Luke and his coauthor, whose first name is escaping me. Last name is Michael. Luke and Michael looked at a very large data set and found that the closer your trees are to a known red-cockaded woodpecker colony, the earlier you harvest them. The more the miles you are from that known colony, the more you’re likely to let them grow a little longer.

And they found that enough habitat was reduced because of pre-emptive habitat destruction between 1984 and 1990 that it would have supported a red-cockaded population sufficient to meet the Fish and Wildlife Services recovery goals. So we wiped out enough habitat to have met the recovery goals because of these really nasty incentives in the Endangered Species Act.

So, what do we do? One of the first things we do is we recognize that regulation doesn’t work. But it makes bureaucrats, interest groups, and politicians—it allows them to pretend that it does. We can say, “Look how much we’ve allocated to endangered species recovery. Look, we’ve established this habitat protection plan. We’ve established this recovery plan. Not that any of that is really going to have any effect on actually recovering the species, but it lets us pretend that it does.”

What the regulation is, the regulations are really, they’re, in effect, an unlimited budget for bureaucrats.

Now, I have to tell you, as a bureaucrat, I like to spend money, especially since it’s other people’s money. And sometimes I have to say, “Wait a minute. You’re acting just like a bureaucrat.”

If I can make rules for people—see, as mayor, if I can get my city council to make rules for people about how they have to live their lives, I can increase all kinds of costs for them and never have to pay for it myself. And so, the unlimited budget is, I can always create more rules whether or not I have an effect.

But what if bureaucrats really had a real budget, a budget that they spent and only had so much of? Might they think differently about how that money gets spent and about the outcomes, especially since you might actually be having to report to politicians about the things you’ve accomplished. Of course, we would lie. We would claim than we’d done more than we had done. We would claim we’re more effective than we’re really being, but could we be worse than we currently are? I don’t know that we could.

Changing the Incentives

So here are some suggestions, some ways to think about the Endangered Species Act. One idea is, let’s change the incentives. For example, we could create something we would call rental contracts. We could come to Michael and say, “Michael, you know, you have all these great plants here, and this particular set is endangered. What if we offer to pay you a bounty, essentially, for producing more? Make it in your interest to produce more as opposed to penalizing you if you produce more?”

What if we went to a farmer and said, “You know, if you just put off doing this activity for a couple of years, this particular species might be able to get itself re-established and then you could go on with your activities.” And pay them to not do that activity for a couple of years. So you give up, postpone or undertake conservation.

I think we might find bureaucrats shopping to find the best ways to actually accomplish their goals. They might act like entrepreneurs instead of like regulators. And if bureaucrats were doing that, it would certainly end the incentives for pre-emptive habitat destruction.

Compensation Funds

Another idea is a form of compensation fund. Now, the most well-known compensation fund is the one that Defenders has called the Bailey Wildlife Foundation Compensation Trust. It shifts—what it does is, if I’m a rancher and I lose a cow, and a calf, five goats, and a pig to a wolf, I get the vet to come and say, “Yup. Sure looks like a wolf did that to me.” The vet signs a form, I turn the form in to the Bailey Conservation Fund and get reimbursed for that value.

Now, you know, any time you have to turn something in to an insurance company, it’s not as good as if you still had what you had. There are always—you know, just the transaction costs of going through the process means that it’s difficult, but it’s sure a heck of a lot better than not getting anything for them.

We were on Lake Powell last week and my wife tried to stop the houseboat from running into a post as we came into the slip. So her hand got hurt rather badly, so we ran to the—there’s a clinic at the Bullfrog Marina, and went to the clinic, and there was a $610 bill from having stitched her up, and getting her the pain meds that she needed so that she could survive the rest of our week, because she wasn’t leaving. So now we have to go through the process of getting reimbursed for the $610.

You have to do the same kind of process here. It’s not perfect, but whatever we get from our insurance company, we’ll be better off than if we didn’t get it. Whatever you get for your cow, and your calf, and your five goats, and your pig, you’re a lot happier than before. And you’ve shifted the cost of having the wolf from you as a farmer to those who really want to have the wolves.

The Delta Waterfowl Foundation is an organization that exists for ducks. They want ducks. Now, it turns out they want ducks because they like to shoot ducks. People who like to shoot things actually pay money, but the Delta Waterfowl Foundation has identified ways of getting farmers to not fill in their prairie potholes in Manitoba, southern Canada, and the northern middle states in the US.

These prairie potholes fill up with water, ducks fly in, they nest, and so they have a program where you can adopt a pothole. You can go to their Web page, and for $125, you can adopt a one-acre pothole. That money goes to the farmer. Now, that’s not very much money, and these ducks aren’t endangered. But if you had a system where you were actually saying, “Create and protect this little wetland. Make it more attractive to the endangered species and we’ll pay you, and the more you produce, the more you’ll pay you.”

They have a system. They put out henhouses and they get 80 percent of the eggs that hatch actually fledge. They fly away. Versus 20 percent when you don’t have the henhouses. It’s pretty darned creative, and it’s really not that expensive to be changing the behavior of the farmers.

They have something called the Alternate Land Use Services. That’s a fair-market value funding that is actually now—this is a partial government program, partial private. Private people put money in, and the government puts money in the special—and in Manitoba, they’re working on this a fair amount. But they’re spending $600,000, and they have gotten farmers to protect over 135,000 acres. Now, that’s like five bucks an acre of prairie potholes, something that is relatively inexpensive but everybody’s happier.

Think about it. If you went out in your back yard tomorrow and there was—somebody had put a Picasso painting out there and it now had your name on it. Now, you may really dislike Picasso and think his work stinks, but you’d be pretty darned happy.

Now think about what would happen if you went into your back yard and found a spotted owl. Some people think that they’re far more valuable than Picasso paintings, but you’d be unhappy because, in the first place, you got the Picasso painting, you can make money from it. In the second case, you have the spotted owl and you now can’t do anything with your back yard. So we’re trying to make it so that having an endangered species is like having the painting.

One possibility, where we have public lands as opposed to just private lands, is a concession, a conservation concession where you actually buy the right to a piece of property, and instead of cutting down the trees, you leave them standing.