Highlights

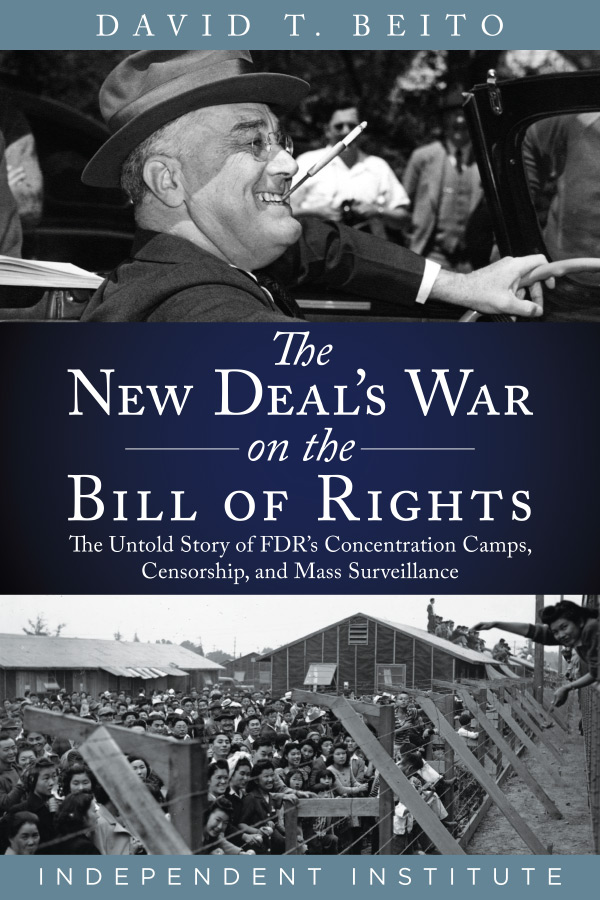

- Franklin D. Roosevelt’s historical legacy is mixed, to put it mildly. Yet, in the twenty-four most respected polls of scholars since 1948, Roosevelt consistently finds a place in the top three “greatest” presidents. This isn’t just because leftist historians dominate the discourse on Roosevelt’s New Deal period, lauding the birth of the welfare state and FDR’s defense of the “forgotten man” (although that certainly has much to do with it). It is because the study of Roosevelt’s attacks on Americans’ rights and liberties has been abysmally neglected—until now. David T. Beito’s The New Deal’s War on the Bill of Rights: The Untold Story of FDR’s Concentration Camps, Censorship, and Mass Surveillance reveals the shameful details of FDR’s extensive abuses of power. This book paints a new and damning portrait of the “fireside” president amid a field of misleading and naive historical literature.

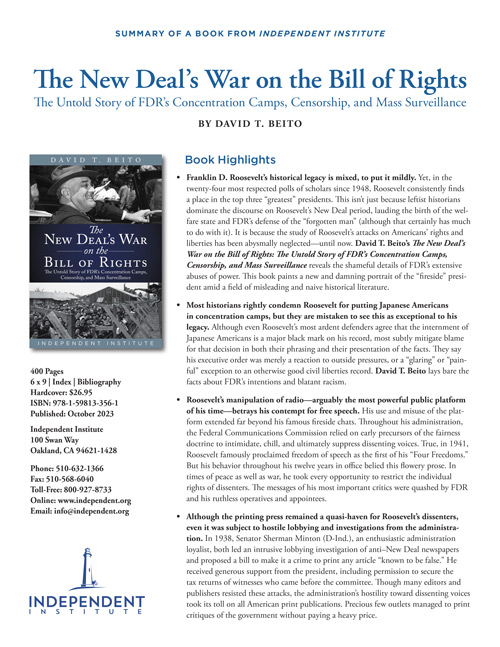

- Most historians rightly condemn Roosevelt for putting Japanese Americans in concentration camps, but they are mistaken to see this as exceptional to his legacy. Although even Roosevelt’s most ardent defenders agree that the internment of Japanese Americans is a major black mark on his record, most subtly mitigate blame for that decision in both their phrasing and their presentation of the facts. They say his executive order was merely a reaction to outside pressures, or a “glaring” or “painful” exception to an otherwise good civil liberties record. David T. Beito lays bare the facts about FDR’s intentions and blatant racism.

- Roosevelt’s manipulation of radio—arguably the most powerful public platform of his time—betrays his contempt for free speech. His use and misuse of the platform extended far beyond his famous fireside chats. Throughout his administration, the Federal Communications Commission relied on early precursors of the fairness doctrine to intimidate, chill, and ultimately suppress dissenting voices. True, in 1941, Roosevelt famously proclaimed freedom of speech as the first of his “Four Freedoms.” But his behavior throughout his twelve years in office belied this flowery prose. In times of peace as well as war, he took every opportunity to restrict the individual rights of dissenters. The messages of his most important critics were quashed by FDR and his ruthless operatives and appointees.

- Although the printing press remained a quasi-haven for Roosevelt’s dissenters, even it was subject to hostile lobbying and investigations from the administration. In 1938, Senator Sherman Minton (D-Ind.), an enthusiastic administration loyalist, both led an intrusive lobbying investigation of anti–New Deal newspapers and proposed a bill to make it a crime to print any article “known to be false.” He received generous support from the president, including permission to secure the tax returns of witnesses who came before the committee. Though many editors and publishers resisted these attacks, the administration’s hostility toward dissenting voices took its toll on all American print publications. Precious few outlets managed to print critiques of the government without paying a heavy price.

- Roosevelt’s attempts to surveil American citizens were unprecedented, aggressive, and unethical. Most Americans consider the birth of the “surveillance state” to be sometime after 9/11, with the passage of the Patriot Act and the establishment of the Transportation Security Administration (TSA). David T. Beito unveils its even deeper—and more sinister—roots. If you really want to know when the government started throwing your right to privacy out the window, then the establishment of the US Senate Special Committee to Investigate Lobbying Activities—also known as the Black Committee, after its chair, Senator Hugh L. Black (D-Ala.)—would be a good place to start. Though rarely remarked upon by today’s historians, this committee monitored private communications on a scale previously unrivaled in US history. Working in tandem with the Federal Communications Commission and the Roosevelt administration, the committee examined literally millions of private telegrams with virtually no supervision or constraint. The targets of this surveillance? None other than Roosevelt’s political opponents—primarily anti–New Deal critics, activists, journalists, and lawyers. So began the modern practice of mass surveillance.

Synopsis

The reputation of FDR, lauded for his New Deal policies and leadership as a wartime president, enjoys regular acclaim. In his own time too, Roosevelt was described as a comforting and competent hero who authored the “Four Freedoms,” wrote the Fair Employment Act, and helped America’s “forgotten man” with groundbreaking welfare programs. Indeed, in the twenty-four most respected polls of scholars since 1948, Roosevelt consistently finds a place in the top three “greatest” presidents.

And yet, critical thinkers must ask: Are historians wearing rose-colored glasses? Is the father of today’s welfare state really worthy of such generous approbation? How much of this glowing reputation is fact, and how much of it fiction? Does he deserve to rank among the greatest presidents America has ever had, next to men like Lincoln and Washington?

Even the most adoring Roosevelt historians agree that the internment of Japanese Americans was a major black mark on his record. But most subtly mitigate blame for that decision in their phrasing and presentation of facts, saying his executive order was a reaction to outside pressures or a “glaring” or “painful” exception to an otherwise good civil liberties record. These assertions are naive to the point of deceit— as the historical facts demonstrate.

In The New Deal’s War on the Bill of Rights: The Untold Story of FDR’s Concentration Camps, Censorship, and Mass Surveillance, historian and distinguished professor emeritus David T. Beito unveils the many abuses of power and human rights violations that defined Roosevelt’s time in office. The New Deal’s War on the Bill of Rights offers much-needed sobriety to the historical literature surrounding FDR, bringing the dark side of his administration to light.

Concentration Camps

Roosevelt’s internment of Japanese Americans stands as a glaring exception in the historical literature’s general neglect of his civil liberties record. No other single deprivation of the Bill of Rights has generated more books and articles. Of course, this attention is merited if measured by the standard of proportionality. In one fell swoop, the federal government snatched away the First through Ninth Amendment protections from some 120,000 men, women, and children, two-thirds of them American citizens.

But whether through ignorance or deceit, historians omit the scope of Roosevelt’s knowledge and intent in this grave matter. FDR himself characterized the incarceration of Japanese immigrants and Japanese American citizens as “concentration camps.” Furthermore, the historical evidence shows that Roosevelt had long considered Japanese Americans to be a suspect group—indeed, private records reveal he considered the Japanese as a whole to be markedly inferior. To cite but one example, as a columnist for the Macon (Ga.) Telegraph, in the 1920s, the future president elaborated on his views on Japanese immigration, writing that “anyone who has travelled in the Far East knows that the mingling of Asiatic blood with European or American blood produces, in nine cases out of ten, the most unfortunate results.” Though he rarely articulated these views so openly as president, his actions and policies betrayed this underlying contempt.

After Pearl Harbor, FDR made sure federal officials attempted to fire up rather than cool down hostile feelings toward the Japanese. In 1942, Executive Order 9066 resulted in mass Japanese American incarceration; that same year, Executive Order 9102 established the War Relocation Authority, to provide for the “removal from designated areas of persons whose removal is necessary in the interests of national security.” The overwhelming majority of Japanese incarcerated cooperated fully, but the WRA and the military did not hesitate to use force for those who did not. Rules in the concentration camps were extensive, including one that mandated all inmates to stay at least ten feet from the fence. When all was said and done, soldiers shot and killed seven unarmed inmates—mostly for failure, either real or perceived, to obey often trivial instructions such as walking on a paved sidewalk. By August, nearly all Japanese Americans on the West Coast were inmates in concentration camps, each characterized by guard towers and armed military patrols.

Censorship

Roosevelt’s fireside chats remain one of the most important aspects of his legacy. No other president depended more on the radio for the success of his administration. His chats and other speeches over the airwaves were instrumental in both selling the New Deal and protecting it. But Roosevelt’s administration owed its success not only to what FDR said over radio, but also to what others did not—or, rather, could not—say. Roosevelt had few scruples about schemes to covertly sideline, or even quash, dissenting radio voices. He was the master of behind-the-scenes intrigue, usually via private sector or governmental intermediaries.

The day after Roosevelt took office, the networks and the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) jointly announced that all broadcasting facilities were on “an instant’s notice” at the service of the administration. Indeed, one of FDR’s top allies was Henry A. Bellows, then the CBS vice president and a former member of the Federal Radio Commission (predecessor to the Federal Communications Commission or FCC). Bellows, a Harvard classmate of FDR’s, promised to reject any broadcast over the network “that in any way was critical of any policy of the Administration.” He elaborated that all stations were “at the disposal of President Roosevelt and his administration.” He specified that CBS had a duty to support Roosevelt, right or wrong, and privately assured presidential press secretary Stephen Early that “the close contact between you and the broadcasters has tremendous possibilities of value to the administration, and as a life-long Democrat, I want to pledge my best efforts in making this cooperation successful.”

But Bellows was just one of many Roosevelt allies in the censorship effort. Friends of the administration in the Department of the Treasury, the State Department, and the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) were all eager to play ball with the administration. Prominent dissenting voices on radio, including Boake Carter and the controversial Father Coughlin, were decisively silenced by these groups, all of which were acting as arms of the Roosevelt administration. Indeed, the putatively voluntary “voluntary code” adopted by the NAB banned the sale of commercial time to discussions of “controversial issues”—i.e., any opinions deviating from those of the administration. The code was enforced by the Code Compliance Committee and the FCC, ensuring rigid compliance from all practical-minded broadcasters not keen to earn the ire of the White House. It became the precursor of the FCC’s Mayflower doctrine of 1941, the most tangible expression of FCC content control and censorship.

Through these means, the Roosevelt administration set the precedent for the flagrant gatekeeping of American debate and discourse. If politicians and bureaucrats in our own time employ similar strategies, we know who paved their way.

Mass Surveillance

Most Americans trace the birth of the “surveillance state” to the Patriot Act, passed in the wake of a terrified post-9/11 America. But David T. Beito contends it was the Roosevelt administration that ushered in a surveillance state the likes of which Americans had never seen.

When a rapid succession of setbacks to Roosevelt’s New Deal took place in the spring and summer of 1935, Senator Hugo L. Black (D-Ala.) took the lead in probing the opposition campaign. Black was a New Deal zealot. Roosevelt gladly gave Black all the power he asked for, and his trust in Black’s judgment was steadfast. Emboldened by this support, Black used a combination of special subpoenas and a highly elastic contempt power to bewilder, harass, and intimidate enemies of the New Deal. Black also asked the US Bureau of Internal Revenue to issue a “general blanket order” for access to the tax returns of his witnesses.

But that wasn’t all. Black also forced telegraph companies to allow his committee to search all incoming and outgoing telegrams sent through Washington, DC. This was unprecedented government surveillance with almost no restrictions. More shocking still, because the committee had directed the subpoena to the telegraph companies, most targets found out—if they found out at all—that their correspondence was being tracked only during their hearing.

When this came to light, American outrage was at an all-time high. The anti–New Deal Chicago Daily Tribune called Black’s committee “terroristic.” Even the establishment publication Washington Post declared that “when private messages are indiscriminately exposed to official scrutiny without the consent of the sender,” this threatens representative government. But the damage was done. In a three-month period, staffers dug through great stacks of telegrams by company employees, lobbyists, newspaper publishers, political activists, and every member of Congress. This was remarkable by 1935 standards, and it remains remarkable today. Some estimate that the committee had examined some five million telegrams during its investigation.

In 2023, this would be akin to staffers’ forming a congressional committee and then joining the FCC at the headquarters of Google and Microsoft to spend months secretly searching all emails for specific names or organizations based on political references.

Despite all this, historians have consistently ignored Roosevelt’s many abuses—until now. David T. Beito challenges the standard orthodoxies surrounding FDR’s presidency, determinedly unveiling the dark side of the fireside president’s legacy. How America views the New Deal and its chief architect—and his chief minions—will never be the same.