David Henderson and Jeff Hummel have managed to ruffle quite a few Austrian feathers with their recent Cato briefing paper, and no wonder: that paper claims not only that Alan Greenspan’s Fed was innocent of any role in encouraging the housing boom but that Greenspan had actually managed to do something Austrian monetary economists have long claimed to be impossible, namely, solve the monetary-central-planning problem. Greenspan, by their assessment, managed to mimic the kind of money-demand accommodating money supply growth that would occur under free banking, thereby achieving (according to their paper’s executive summary) “a striking dampening of the business cycle.”

To be sure, Henderson and Hummel do not see Greenspan’s supposed achievement as justifying central banking. On the contrary, they make clear their “preference” (the word, again, comes from the executive summary) for free banking. Nevertheless, their argument supplies ammunition to apologists for central banking. After all, if the choice between free banking and central banking is merely a matter of “preference,” rather than a choice between arrangements with inherently distinct capacities for either limiting or exacerbating business cycles, then there are strong prima facie grounds for dismissing radical and (recently) unproven alternatives in favor of the status quo.

But are Henderson and Hummel’s claims valid? Contributors to the Mises blog, including Robert Murphy (“Greenspan not to blame?”), have attempted to counter Henderson and Hummel’s arguments largely by pointing to various alternative measures of money that appear to suggest faster money growth earlier this decade than the measures Henderson and Hummel themselves emphasize. In my opinion, such efforts miss the real problem with Henderson and Hummel’s analysis, which is precisely that one cannot accurately gauge the easiness of monetary policy by looking at money-stock measures alone. Instead, one must look at measures that indicate the relationship between the stock of money on one hand and the real demand for it or, if one prefers, its velocity. What matters isn’t how rapidly the money stock grows, regardless of how one chooses to measure it, but whether its grows faster than the public’s demand for real (that is, price-level-adjusted) money holdings. Even a low, a zero, or a negative absolute growth rate for some money-stock measure can prove excessive if demand for the monetary assets in question is declining. Regarded in light of this consideration, Greenspan’s monetary policy was in fact “easy,” as I will endeavor to show.

The Housing Boom and Fed Policy

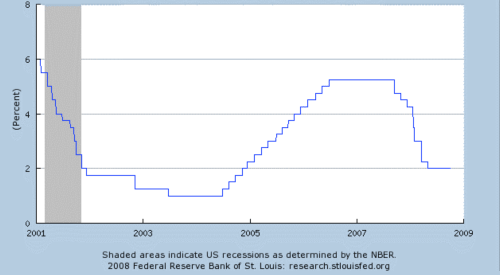

Those who hold the Greenspan Fed partly to blame for the housing bubble typically offer as evidence its having held the federal funds rate at the extremely low level of 1% for an extensive period of time after having reduced it to that level in stages following the collapse of the dot-com bubble. As I put it in an August 31, 2007 article in the Christian Science Monitor,

Why did mortgage lenders earlier this decade start showering credit as if it were spewing from a public fountain? The answer is that credit was spewing from a public fountain—and that fountain was the Fed. In December 2000, the Fed began an unprecedented year-long series of rate cuts, reducing the federal funds rate from over 6 percent to just 1-3/4 percent—a level last seen in the 1950s. By mid-2003, two further cuts had reduced the rate to just 1 percent.

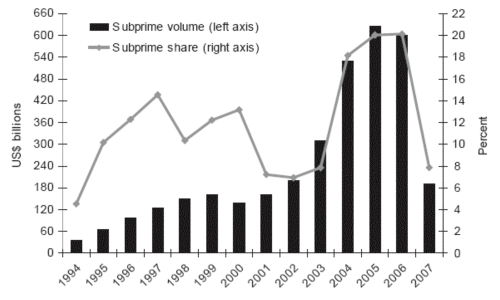

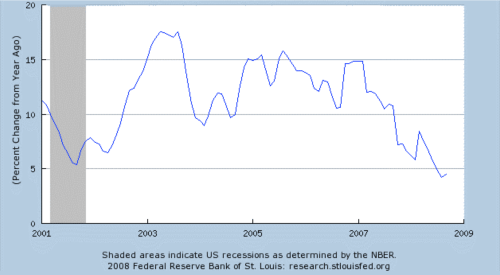

The correlation between the Fed’s moves and the volume of subprime lending is in fact striking, as can be seen by comparing relevant charts, from the St. Louis Fed’s FRED database and Inside Mortgage Finance, respectively:

Chart 1: The Federal Funds Rate Target

Chart 2: Subprime Mortgage Originations

Although it’s true that subprime lending peaks in 2005–6, or some two years after the federal funds rate target reached its trough, this fact is perfectly consistent with the well-known tendency of monetary policy changes to influence other aspects of economic activity only following “long and variable lags.” In this particular case, the Fed’s low-target-rate policy had its more immediate effect on general real-estate lending. The share of subprime loans exploded only after 2003, thanks in part to regulatory causes independent of Fed policy, such as have been very well described by Stan Liebowitz.

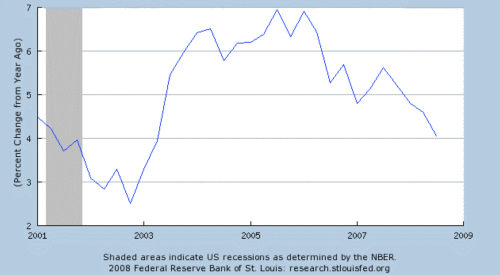

Chart 3: Real Estate Loans, All Commercial Banks

Monetarism Misunderstood

Although evidence such as that reviewed above has been taken by many, including no less a monetarist than the great Anna Schwartz, as compelling grounds for holding Greenspan at least partly to blame for the housing bubble, Henderson and Hummel dismiss it on the supposedly monetarist grounds that what really matters is the behavior of various money-stock measures, including the monetary base. According to them, all such measures suggest “that monetary policy was not all that expansionary during 2002 and 2003 under Greenspan, despite the low interest rates.”

It’s true that, once upon a time, Milton Friedman argued that sound monetary policy was just a matter of having M2, or some such money measure, grow at a modest and constant rate approximating the anticipated long-run growth rate of real output. It’s also true that Friedman later argued for a more extreme money-growth rule, consisting of a rule to freeze the monetary base. But Friedman abandoned his original growth-rate rule in response to the evident passing, following the inflation of the 1970s and consequent financial innovations, of the stability of velocity upon which its success was predicated. As for the frozen-base proposal, Friedman was careful to accompany it, as free bankers (myself included) have accompanied their similar proposals, with a call for more complete financial deregulation: Friedman never suggested that a frozen or relatively constant monetary base, however measured, could be taken as evidence of the sound conduct of monetary policy in a heavily regulated monetary system such as prevails today, where banks cannot issue currency and are subject to legal reserve requirements. These and other legal restrictions on commercial banks tend to undermine their capacity to automatically accommodate changes in the demand for money with appropriate changes in the supply of (private) money. Consequently, the prevailing regime is one in which the avoidance of monetary excess or shortages calls for frequent changes to the monetary base, that is, for adherence to some more elaborate monetary rule, if not for monetary discretion.

Yet Henderson and Hummel believe just the opposite. According to them, Greenspan, by championing reforms that supposedly served to “deregulate the broader monetary aggregates” during the 1980s and early 1990s, succeeded in establishing a system in which changes in money’s velocity were automatically offset by changes in its amount—just as Larry White and I (and, at least implicitly, Milton Friedman) predict would happen under free banking. But which of these reforms abolished reserve requirements, or allowed banks to issue their own paper currency? Putting that question aside for the sake of argument, it remains an easy matter to test Henderson and Hummel’s claim. As the equation of exchange, MV=Py, informs us, if changes in V tend to be offset by changes in M, that fact should translate into a relatively stable value of corresponding measures of nominal spending, Py.

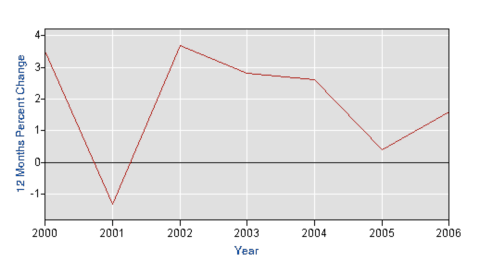

So how did Py actually behave during the period in question? Here is a plot for one popular measure, final sales of domestic goods (other measures show very similar patterns):

Chart 4: Final Sales of Domestic Goods

Evidently, whatever M was up to during the housing boom, it was not simply adjusting so as to offset opposite changes in V. If it had been, final sales and other similar measures would have been constant. In fact, final sales, which had been growing at modest annual rates between 2.5 and 3.5 percent during the year or so following the end of the dot-com recession, accelerated rapidly thereafter. In 2004 the growth rate exceeded 6 percent, and by 2006 it was just shy of 7 percent. How fast is that? Well, a monetarist would have nominal spending grow no faster than the expected growth rate of real output, which, based in recent experience (for either final or gross domestic product) is between 2 and 3 percent, so as to keep the expected rate of inflation close to zero. By this reckoning, the annual rate of money growth during 2003–2006 was too rapid by a long chalk.

Indeed, it was too rapid even relative to a less strict goal of keeping the inflation rate at around 2 percent, such as has been popular among relatively responsible central bankers in recent years, including those who rely on the so-called Taylor rule for adjusting interest-rate targets in response to deviations of inflation and employment from their desired values. John Taylor him self has made this point, in a paper in which he argues that the Fed should have begun raising the federal funds target, not in mid 2004, but towards the end of 2001, when it was still well above 1 percent.[1] Doing so, Taylor claims, “would have avoided much of the housing boom”—about a third of it, to judge by Taylor’s own simulations.

But that, in my opinion, is being far too charitable. As I’ve argued in my pamphlet Less Than Zero and (more briefly) elsewhere, and as many other economists have argued before me, even zero inflation is too much when an economy is experiencing overall improvements in productivity. Sound policy in that case calls for deflation at minus the rate of productivity growth. (The opposite is also true: if productivity declines, prices should be allowed to rise to reflect the new reality of increased unit production costs.) Taking such a “productivity-norm” ideal into account, and referring to total factor productivity growth as shown in Chart 5, one arrives at the conclusion that the Fed ought to have begun raising the federal-funds-target-rate somewhat earlier than Taylor suggests, and far more aggressively. It follows that, in light of a productivity-norm perspective on sound monetary policy, Greenspan’s Fed may deserve, not only a large share of blame for the housing bubble but the lion’s share.[2]

Chart 5: Total factor Productivity, All US Manufacturing

Conclusion

David Henderson and Jeff Hummel deserve to be congratulated for their eloquent defense of Alan Greenspan. It is, I think, as compelling a defense as could be raised on his behalf. Why two anti-central-bank libertarians would bother to undertake such a defense—and a pro bono defense at that—is an interesting question that several bloggers have raised. Personally I have no doubt that they have done it because they sincerely believe Greenspan to be innocent, and that claims to the contrary are based on bad monetary analysis.

But whatever their purpose they’ve performed a valuable service not just to Greenspan himself but to monetary economics, for in putting Greenspan’s actions in the most favorable possible light, they have posed a challenge to those of us who insist that a persistently sound central-banking policy is not only unlikely but beyond the ken of mere mortals, and that even the best of possible central bankers must eventually steer the economy he is piloting into disaster. Whether that challenge has been met here is for others to decide.

Notes

[1] Unlike Henderson and Hummel (p. 5) Taylor also rejects Greenspan’s “global savings glut” defense. Using IMF data he shows that global savings actually declined as a share of world GNP from 25 percent in the 1970s to 21 percent between 2003 and 2005.

[2] I am presently looking into replicating Taylor’s simulations for the productivity-norm case.