The 2020 experience suggests that monetary and fiscal actions to stimulate output and spending are ineffective in speeding the economic recovery. But they do redistribute wealth to those with lower incomes and transfer debt from the private to the public sector.

Economists tend to attach themselves tightly to their theories and may well find it unthinkable that their prescriptions might not work. But in the end the stimulative effect of government actions such as paycheck protection packages and quantitative easing on national output and spending is an empirical question. No established body of empirical evidence demonstrates their efficacy. Rather the reverse is true—the case for skepticism has existed for decades[1] and the 2020 experience has strengthened it.

Q. The monetary and fiscal policies of 2020 were the most expansionary in history. What evidence would you cite for doubting their effectiveness?

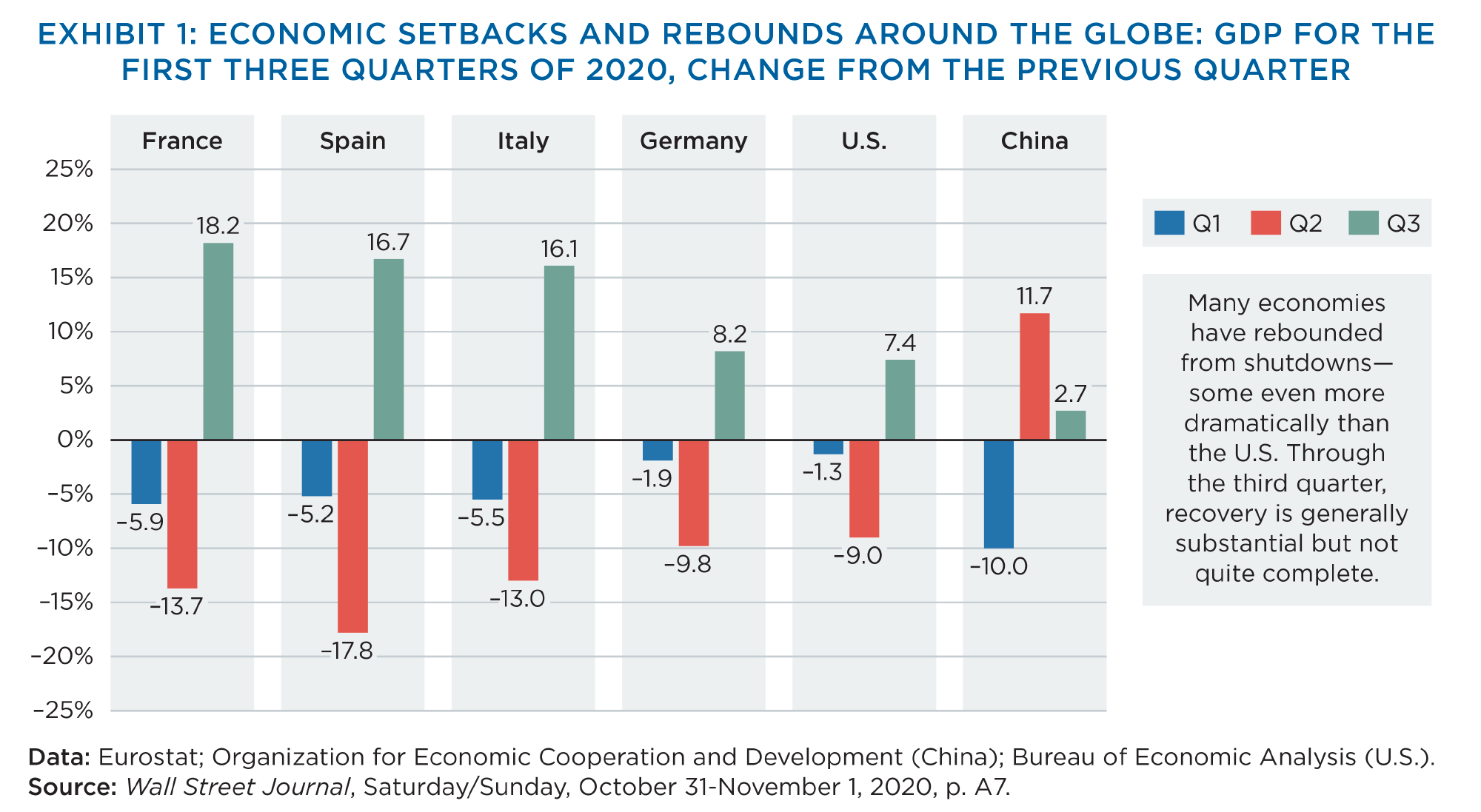

First, there’s the international picture. A handy chart by the Wall Street Journal (redrawn as Exhibit 1) illustrates how economies around the world tumbled early in 2020 and then rebounded. Although some governments enacted much more “stimulus” than others, the vigor of the recoveries was quite similar from country to country.

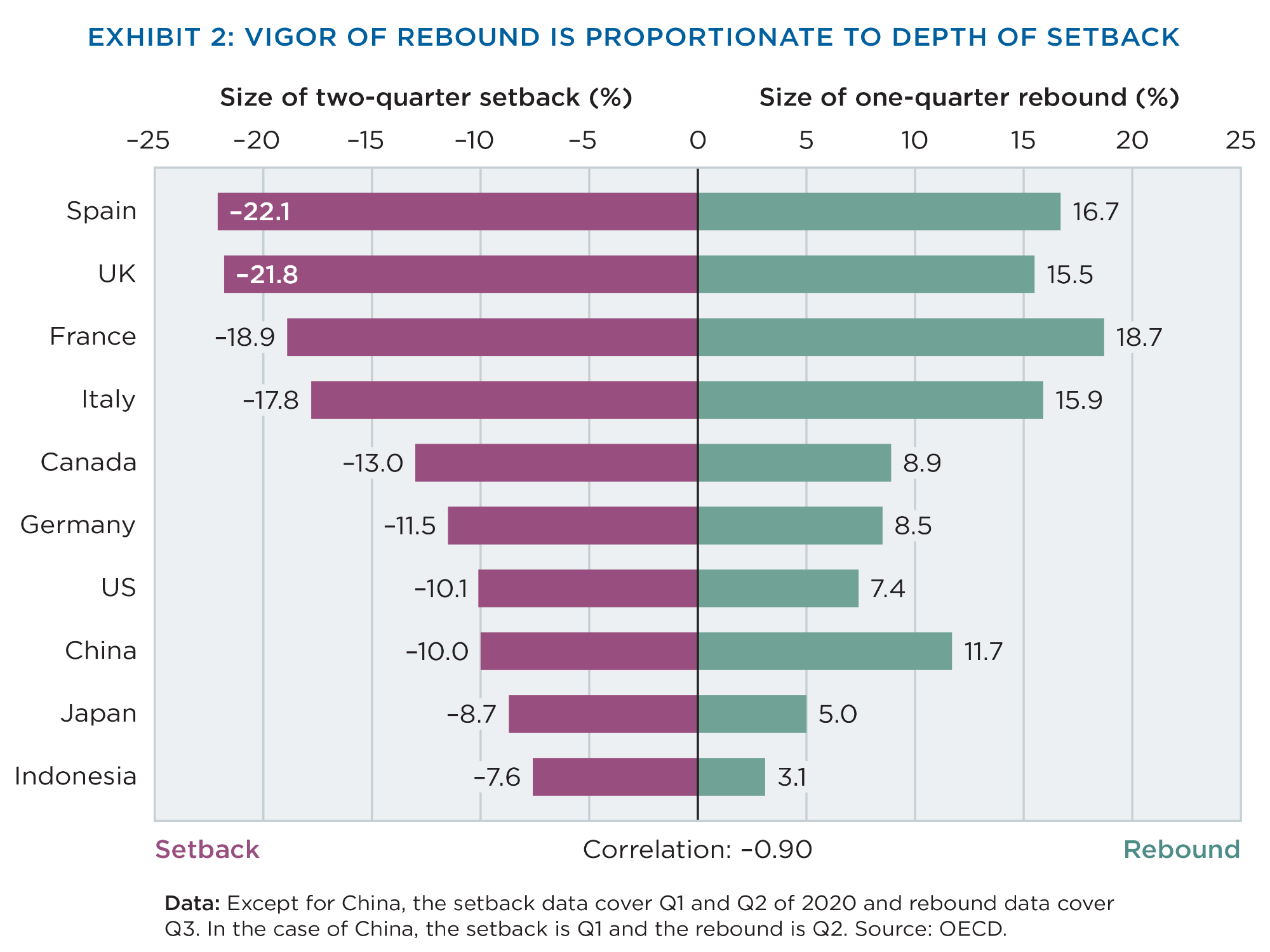

Stimulus efforts ranged in scale between an estimated 11% of GDP in the United States to 4.9% in Germany and 1.2% in China.[2] Germany experienced a larger economic rebound than the United States, despite a stimulus effort that was only half the effort relative to the size of its economy. China, with only one-tenth the U.S. effort, enjoyed an even larger rebound. Indeed, no connection is evident between the size of the GDP rebound and the size of the stimulus effort. Instead of a strong correlation between stimulus and recovery, we see a pattern in which the vigor of recovery was roughly proportionate to the depth of the setback that preceded it, as Exhibit 2 illustrates.

Q. So you think something other than monetary and fiscal policy could explain these economic rebounds?

Yes, the more complete the government-imposed economic shutdown, the more severe the setback. And the more complete the reopening, the more impressive the recovery. That simple explanation must be the decisive factor. The correlation is –0.9 and statistically significant, especially when the sample of countries is expanded to ten.

This interpretation is reinforced when we consider timing evidence. GDP setbacks occurred in sync with economic shutdowns, and recoveries occurred in sync with re-openings. China provides a major clue. The Chinese authorities shut down their economy several months earlier than did the United States and Europe, and they lifted the shutdown several months before the other countries did. China’s rebound likewise preceded recoveries elsewhere.

Q. In the United States, didn’t the recovery follow aggressive action by the federal reserve and treasury department?

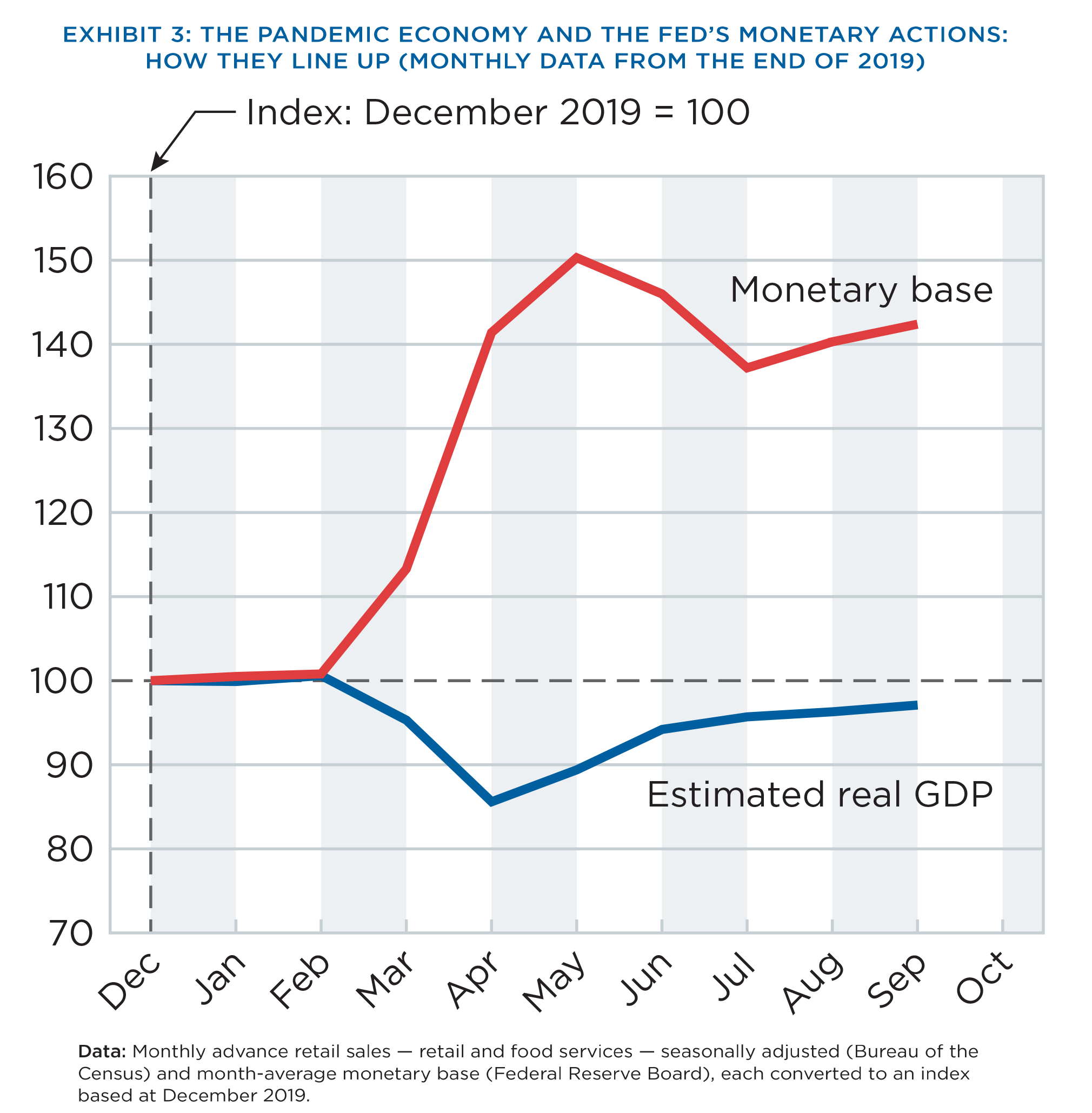

Yes, but if their actions were causal, their effect occurred later than one might expect. In fact, fiscal and monetary “stimulus” efforts grew most rapidly just as the economy was tumbling to its bottom. And in the second half of 2020, the economic recovery maintained its momentum after benefit programs enacted in the spring expired and the Fed’s efforts paused.

Q. So you don’t see any connection between the scale of the Fed’s operations and the path that the U.S. economy followed?

The connection is strong, but it’s the opposite of what most people believe. More often than not, the economy drives Fed policy. As Fed officials say, they are “data driven.” Exhibit 3 compares the monthly performance of real GDP with the growth of the monetary base, which is a broad measure of the Fed’s stimulative actions.

In 2020, the economy simply came back as the shutdowns lifted.

Q. What about the correlation between fiscal policy and the economy?

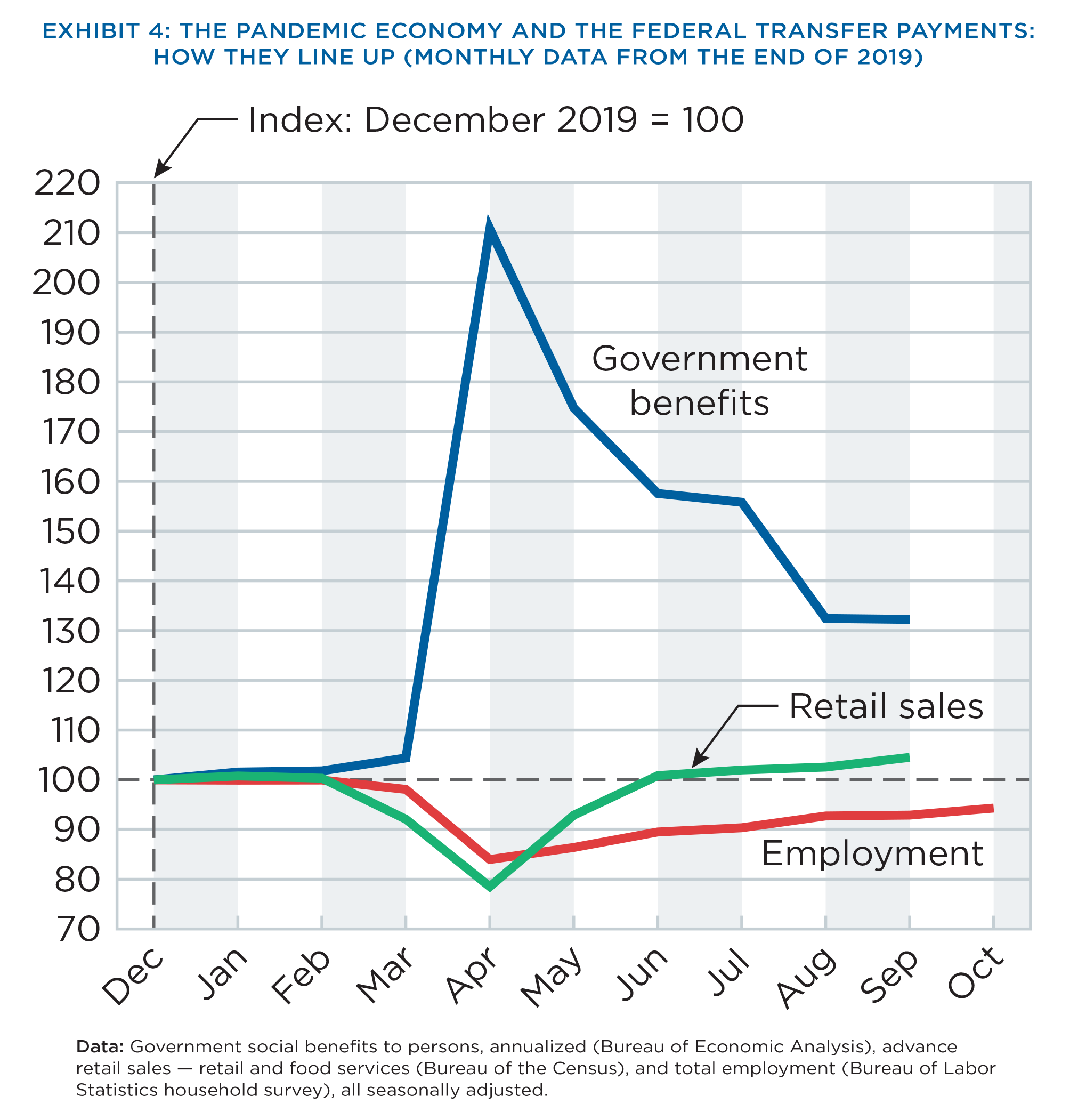

Government relief payments are similarly driven by economic variables. (See Exhibit 4.)

Retail sales recovered more quickly and more fully than employment. But both continued to recover despite the inability of the political parties to agree on further “stimulus” packages until the end of 2020.

Q. What do you think all of the evidence shows?

Monetary and fiscal stimulus policies are correlated inversely with the path of the economy. Causation runs from economic performance to government action. When the economy drops, monetary and fiscal expansion increases; and when the economy recovers, relief payments drop back. The same pattern has been observed recession after recession. Any causal link running in the other direction is weak enough to be invisible.

So, although no proof is possible, the circumstantial evidence is suggestive. The conviction expressed by proponents of large-scale “stimulus” policies is not justified by facts. It’s mainly a matter of doctrine and belief.

Q. What does longer-term historical evidence tell us about the effectiveness of government stimulus?

In earlier work I reported “copious evidence covering many decades” showing that government stimulus tends to “restrain the performance of output, employment and stock prices.”[3]

Q. How would you explain an inability of government policy to stimulate the economy?

As far as monetary policy is concerned, part of the explanation is that an increase in bank reserves (and hence the monetary base) doesn’t translate automatically into an increase in bank lending and economic activity. Demands on the part of potential borrowers would have to be unmet. The experience of 2008–09 shows that such unmet demands don’t necessarily exist—even in a deep crisis. In other words, the volume of bank credit is demand-driven and not supply-driven.

Q. Why else do economic stimulus efforts fail?

Economists know that recipients of temporary windfalls or insurance payouts mostly save rather than spend such income (saving includes not only abstaining from consumption, but also the paying down of debt). The underlying principle, advanced by Milton Friedman and for which in large part he received a Nobel Prize in 1976, is known as the Permanent Income Hypothesis (PIH).

Q. What is that principle?

The Permanent Income Hypothesis states that spending is proportionate to the sustained or “permanent” fraction of a consumer’s income rather than its “transitory” share. Friedman’s hypothesis implies that any unusual income boost largely will be saved or used to pay down debt.

Q. What does that say about the effectiveness of government stimulative efforts?

Transitory income would include benefits in any form paid out by the government for the purpose of kick-starting the economy. Additional evidence applies to the current economic situation. The U.S. personal saving rate jumped from a normal 7% in the fourth quarter of 2019 to 25% in the second quarter of 2020, as the economy nosedived and large-scale fiscal stimulus began. In the third quarter the scale of relief payments fell, and the saving rate came down.

Q. Is the PIH relevant to monetary policy?

Yes. While not usually part of the discussion, so-called “helicopter money” is just another form of transitory income. Professor Friedman asked readers to imagine what would happen if the government of the most primitive economy conceivable were to print a load of dollar bills and drop them on the ground from a helicopter.[4] Although people would collect and try to spend the money, he argued that it would not boost the economy without a corresponding increase in the supply of goods and services. There would be “too much money chasing too few goods,” resulting in price inflation.

But Friedman could have taken his argument a step further. Imagine a slightly less primitive economy in which the people have access to banks. The Permanent Income Hypothesis suggests that they would not try to spend the windfall immediately but would at least initially deposit most of it in their bank accounts. Having no need of larger cash balances, they would convert the excess holdings into financial assets—or pay off debt. The banking system’s balance sheet would expand by the amount of the unwanted cash. The private sector would end up with more wealth on the assets side of its balance sheet, less debt on the liabilities side, or both. The economy would continue on as before.

Q. And the inflationary effect?

Rising prices would not be a risk. The quantity of money in circulation would be unchanged, as would be the demand and supply of goods and services.

Q. What would this interpretation imply about modern monetary theory?

Printing money and distributing it to people who wouldn’t spend it would neither stimulate growth

nor push up prices. That conclusion seems to fit what we are experiencing in the real world. It certainly could change the distribution of wealth, though.

Q. In what way would it do that?

If government benefits and “free money” are saved by recipients rather than spent, then the net result boils down to a redistribution of debt and wealth between the public and private sectors as well as within the private sector.

Debt is transferred from the private to the public sector. Governmental gifts of money and income are financed largely by debt, and all government debt sooner or later must be serviced (interest paid to its holders) by taxation. The discounted present value of those future taxes is wealth that taxpayers lose and that recipients of government relief gain.

Q. So if the economy doesn’t benefit from government “stimulus” spending, how should policymakers respond to recessions?

Monetary and fiscal relief have some humanitarian justifications in a “crisis,” but what the economy needs for recovery is to be left free to heal itself rather than be flooded with unproven economic remedies, especially when the crisis is created by the government in the first place. Public policy should promote resilience and not dependence. Proposals to redistribute income or wealth should be based on the explicit consent of the electorate.

Notes

[1] See David Ranson, “Half a dozen reasons for distrusting stimulus’ packages,” Economy Watch, HCWE & Co., January 25, 2008.

[2] “Visualizing Coronavirus Stimulus Programs Around the World”.

[3] David Ranson, “Why federal government ‘stimulus’ doesn’t stimulate,” Strategic Asset Selector, HCWE & Co., June 30, 2012, p. 6.

[4] David Ranson, “Helicopter money — common sense or wishful thinking?” Interest-Rate Outlook, HCWE & Co., June 24, 2016.

The data in the illustrations in this report are up to date as of December 2020. Updated versions are available from the author on request to [email protected].