Problems with identifying legitimate voters are much more serious than anyone is acknowledging.

A 2012 study by the Pew Center on the States found that one out of every eight active registrations were inaccurate or invalid, 1.8 million voters listed as “inactive” were actually deceased, and 2.8 million voters had active registrations in more than one state. Another nationwide report released in August by the University of Arizona’s investigative reporting project, News21, pointed to some 900 cases of alleged voter registration and absentee voter fraud.

The numbers could be significantly higher because fraud is not always easily discovered. Ineligible felons were able to cast votes in Minnesota’s 2008 senatorial race and may have determined the result of that election. In North Carolina this year, “disability rights” activists are alleged to have “assisted” mental hospital patients in completing absentee ballots. In Virginia, the son of Northern Virginia Rep. James P. Moran Jr. was forced to resign from his father’s campaign, the Washington Post reported, “after an undercover video showed him discussing possible voter fraud with an activist posing as a campaign worker.”

As one post-election headline put it: “Election Day Voter Fraud, Bullying Widespread.”

Our voting system is clearly being abused, and both parties should want to address the problem together.

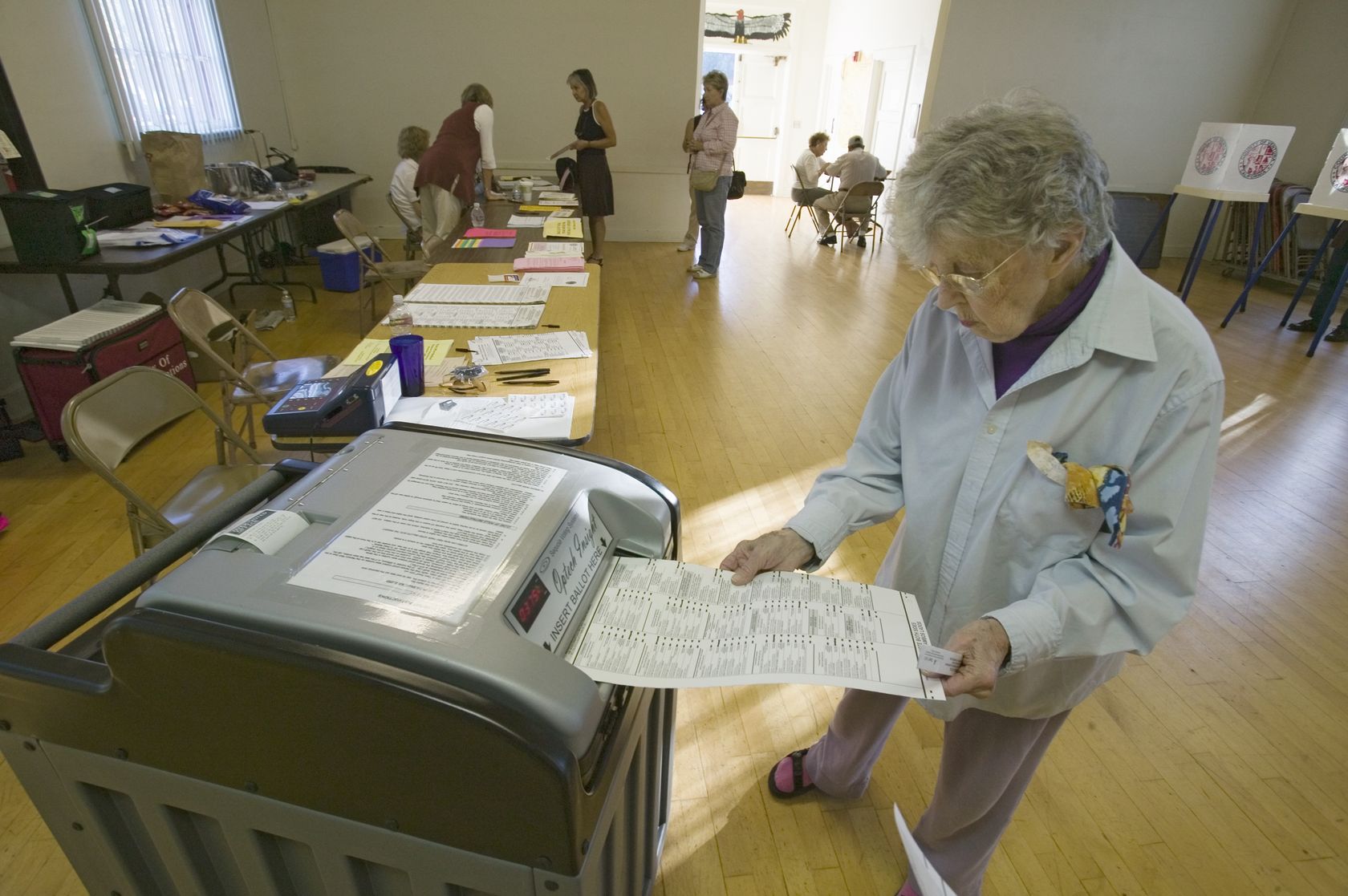

Critics are right that photo IDs will not necessarily prevent registration or absentee fraud. Still, ID laws could positively affect public perception of the voting process, which is believed to have suppressed voter turnout in recent elections.

Indeed, despite the weeks of nonstop advertising, the Center for the Study of the American Electorate reports that voter turnout this year was lower than in the two previous presidential elections, with just 57.5 percent of eligible voters exercising their right, compared to 62.3 percent in 2008 and 60.4 percent in 2004.

If we want to get the number of participating voters higher, widespread belief in a secure and accurate polling system is essential.

At the same time, proponents of voter ID laws need to take criticism seriously. Any policy that fetters the exercise of a person’s right should be met with intense scrutiny. The burden of proof showing that the policy responds to a legitimate need and is not disproportionately restrictive or demanding rests with the proponents of that policy. There are people who don’t have government IDs and for whom obtaining one would be difficult. While this group represents a very small percentage of the population, their rights must be protected.

The Brennan Center for Justice claims that voter ID laws could negatively affect 11 percent of the voting age population. Since some 40 percent of the voting age population doesn’t vote, and many people without IDs are not even registered to vote, the number of people who might really be affected would be much lower.

Obviously, there are trade-offs. Voter ID laws are not that onerous, but their real benefit probably is limited as well.

As a matter of principle, it seems obvious that voting requirements should be on equal footing with requirements to enter federal buildings, to board an airplane or to buy a gun. All require photo ID.

Both sides should agree that reducing voter turnout is not a good thing and would cut against any positive benefit ID laws might have.

Rather than fighting the voter ID concept, critics should work with proponents to come up with innovative ways to get IDs for people who can’t do so themselves. This is not an insurmountable problem. We have Meals on Wheels, surely we could develop something similar for identification?

We need creative solutions from those who really care about making our democratic republic work the way it should. The first step, as usual, is admitting we have a problem. That is obvious. With the next federal election two years away, we have plenty of time to fix it.