Marcelo Capobianco is a butcher in Buenos Aires, where he works in a white-tiled room surrounded by dangling hooks, slabs of beef, and a sign that reads “Long live freedom!”

He livestreams prices on Facebook daily, but like many merchants in Argentina, he uses chalkboards in his store so he can update prices throughout the day as pesos lose their value.

The New York Times, which recently interviewed Capobianco, reported on the inflation that “has convulsed Argentina” and led to the rise of Javier Milei, who last week became Argentina’s first libertarian president (and arguably the first libertarian president in the world in modern history).

Prior to Milei’s stunning victory, inflation in Argentina hit 143 percent. Triple-digit inflation has helped push 40 percent of Argentines into poverty and has led to a surge in demand for US dollars.

An estimated $200 billion in US currency has gravitated toward Argentina’s $487 billion economy, the Times estimates, nearly 10 percent of all US dollars in circulation (more than any other country in the world except for the USA).

The appeal of US dollars in Argentina should come as little surprise. The purchasing power of the peso is depreciating so fast that people continually swap them out for dollars, which are hoarded.

“You’re constantly gathering up money quickly in order to buy dollars,” a 30-year-old supermarket worker told the newspaper, “because the next day, it’s devalued again.”

To give you an idea of how hard Argentina’s peso has fallen, today a single US dollar purchases 1,000 pesos. In 2019, a dollar bought 48 pesos. In 2011, a dollar could be exchanged for 3.45 pesos.

Ignoring the Elephant

The Times story is solid and worth reading, but its primary focus—beyond the collapse of Argentina’s currency—is the dollarization of Argentina’s economy.

During his presidential campaign and since his electoral victory, Milei proposed abandoning the peso altogether and embracing the US dollar as Argentina’s official currency. The Times argues this would be difficult and would not immediately solve Argentina’s economic woes.

Both of these claims are true, but scrapping Argentina’s central bank would largely solve one of Argentina’s biggest headaches.

“If you dollarize, you get rid of inflation,” says Daniel Raisbeck, a policy analyst on Latin America at the Cato Institute, “and you get rid of the currency devaluation problem, which is a huge problem in Argentina.”

Killing triple-digit inflation won’t fix all of Argentina’s economic problems, which are decades in the making and stem from its embrace of Peronism (a blend of fascism and national socialism). But it can prevent Argentine politicians from painting over its economic problems by simply printing pesos, which is precisely what Argentina has done for the last 25 years (more on that shortly).

This brings me to my primary complaint with the New York Times story.

The reporters do a splendid job showing the serious harm inflation has wrought on Argentina’s 46 million people, but they spend very little time examining how inflation arrived in Argentina.

The Times asserts that Argentina’s economic woes stem from a variety of factors, ranging from overspending and large deficits to protectionist trade policies and currency controls, before citing an “overreliance on printing more pesos to pay the government’s bills” as a contributing factor.

Now, dollarization is actually a remedy to many of these problems, because most of them—particularly overspending—are enabled by money printing. But the real problem is that the Times, in a story on inflation, spends ten words explaining its direct cause.

Argentina’s Inflation Explained in One Chart

Though the Times opted to downplay the monetary elephant in the room, it’s a topic worth exploring. Argentina is hardly the only country struggling with inflation, after all, and there’s a great deal of confusion about what inflation is and what causes it.

Both in the United States and Canada, two countries that have struggled with surging consumer prices since 2020, politicians have argued that inflation is the result of greedy corporations who are price-gouging consumers.

“It’s corporate greed, pure and simple,” Sen. Elizabeth Warren recently said. “I’ve got a plan to tackle their price gouging and break up big monopolies that hit families with higher costs.”

In Canada, lawmakers have gone so far as to threaten grocery chains with new taxes if they don’t reduce food prices, and they have also threatened to drag CEOs before Parliament.

To the Times‘ credit, the paper doesn’t entertain the fatuous notion that Argentina’s inflation is the result of greedy entrepreneurs. And for good reason.

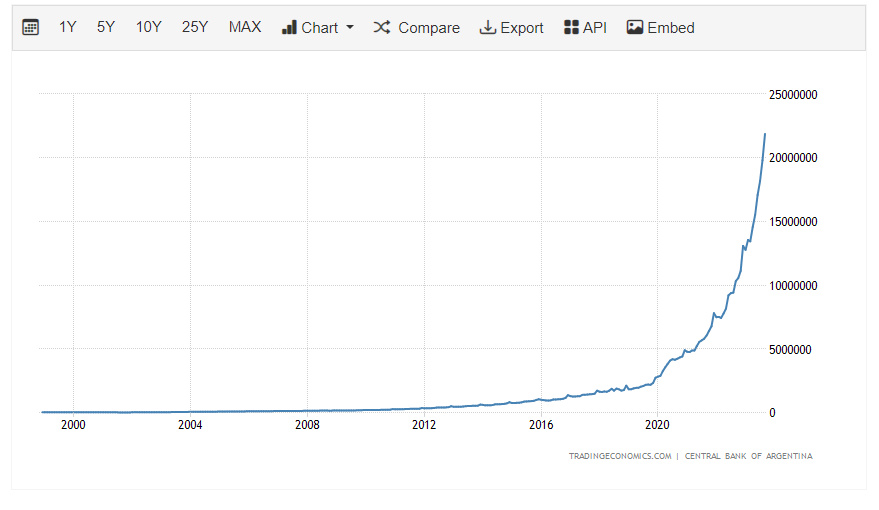

Anyone seeking to understand Argentina’s inflation need only look at its money supply in recent decades (see below).

In 1990, Argentina had 711 billion pesos (ISO 4217 code: ARS) in circulation. By 2020, Argentina had roughly 2.5 trillion pesos in circulation. In other words, the Argentine government nearly quadrupled the amount of money in circulation over a 30-year period.

That’s a massive increase in the money supply, even over three decades, which explains why Argentina has battled inflation for years. Yet it’s small potatoes compared to Argentina’s recent money printing.

As of September 2023, Argentina’s total money supply stood at 22 trillion pesos, which means the government expanded the money supply nearly tenfold in less than four years.

Economics 101

This is why the people of Argentina are suffering massive inflation.

It’s Economics 101. Practically any econ textbook you pick up will tell you that if you expand the money supply faster than an economy can produce goods and services, you will have inflation.

Too many people ignore the reality that inflation is first and foremost a monetary issue.

The Nobel-Prize-winning economist Milton Friedman famously said that inflation “is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon,” but it’s not like Friedman is alone. This is a truth widely understood in economic circles.

“I think almost everything other than the Federal Reserve is a sideshow when it comes to the dynamics of inflation,” Jason Furman, one of President Barack Obama’s top economists, responded last year when asked about Warren’s “greedflation” theory.

This simple explanation for inflation is one many are disinclined to accept, however, and not just political partisans who speak of “greedflation.” We often hear suggested such things as hot labor markets and disrupted supply chains as causes of inflation, or declining gasoline prices as evidence of cooling inflation.

There’s a simple reason there’s so much confusion on the issue: The definition of inflation has changed over time.

Today many people, including economists, confuse increases in price with inflation. Think about how inflation is reported: The government measures consumer prices, and this tells us how much “inflation” there is in an economy.

There are several problems with this approach, however, including the fact that prices are constantly changing for reasons that have nothing to do with inflation, including supply and demand. (The price of gas, which are heavily influenced by crude oil supplies, is one of a million good examples.)

Inflation was not originally defined as an increase in consumer prices. For generations across various countries, inflation was defined as an expansion of the supply of money in an economy.

“Inflation, as this term was always used everywhere and especially in this country, means increasing the quantity of money and bank notes in circulation and the quantity of bank deposits subject to check,” the economist Ludwig von Mises pointed out in Economic Freedom and Interventionism. “But people today use the term ‘inflation’ to refer to the phenomenon that is an inevitable consequence of inflation, that is the tendency of all prices and wage rates to rise.”

Mises saw the devolution of the term as a kind of tragedy, since there was no longer “any word available to signify the phenomenon that has been, up to now, called inflation.”

The Austrian economist was right, but there’s an obvious reason many today prefer the new definition of inflation.

Under the former definition, it was easy to spot the culprits of rising prices: It was always and only those who expanded the money supply. Whereas under today’s definition, as Senator Warren shows, a general increase in consumer prices can be blamed on just about anyone or anything.

Americans should not be fooled. Whichever definition one prefers to use—an expansion of the money supply which leads to price increases, or a broad and sustained increase in consumer prices—inflation is caused by the governments and central banks who control the money supply.

Which brings us to the United States. A glimpse at the steady expansion of the US money supply shows why prices in the US are also rising at a historic clip, and why its current fiscal path—which includes adding nearly $20 trillion to the $34 trillion national debt over the next ten years—is a cause for grave concern.

“If a government resorts to inflation, that is, creates money in order to cover its budget deficits or expands credit in order to stimulate business, then no power on earth, no gimmick, device, trick or even indexation can prevent its economic consequences,” the Austrian economist Hans Sennholz once observed.

This is not to say the fate of the United States must be that of Argentina. But if politicians continue on their current course of money expansion and massive deficits, Americans will likely one day find themselves in a situation much like Marcelo Capobianco—using chalkboards in their stores to update prices throughout the day as they do business.