College enrollments in the humanities have declined, even more than the general fall in the numbers attending college. West Virginia University recently laid off numerous faculty in the humanities, especially foreign languages, and other schools have done so on a smaller scale.

Moreover, graduates in such humanities as foreign languages or English literature on average fare less well than many other majors in the job market. In a recent talk to public university trustees in Ohio, I noted that two determinants of post-college vocational success are the perceived quality of the school where the student graduated and the field of study. Unless things change substantially, today’s accounting and engineering majors are more likely to be driving fancy cars and belonging to the country club two decades from now than are those majoring in philosophy or English. Markets appear to be working: Enrollment shifts suggest resources are moving from less productive uses (studying English and philosophy) to more productive ones (studying accounting, economics, and electrical engineering).

Nonetheless, I have been increasingly uneasy about some attacks on the humanities by politicians, university governing boards, and others. The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (AAAS) has published a new report, using “five years of pooled data” from the American Community Survey of the Census Bureau, showing that in all but four very small states, humanities college graduates make over 40 percent more after school than do high school graduates. College French majors do not fare as well as economists, but they still fare far better than high school graduates—ignorance is not economic bliss. Moreover, from my study of the Census data compiled by AAAS, the humanities graduate also makes more than education graduates and earns nearly the same on average as those in the behavioral and social sciences. For example, in New York the median earnings of humanities graduates—$83,822—was less than 3 percent smaller than that for behavioral and social science graduates ($85,641), and about 90 percent higher than median high school graduate earnings. Studying Shakespeare in college is not financially debilitating.

Speaking personally, three score and four years ago, I was an economics major at Northwestern University and liked my courses and professors enough that I successfully made that field my career. But the three individual courses that I most fondly remember today were one in English literature, where professor Bergen Evans captivated an audience of literally hundreds interpreting King Lear for weeks on end; a similar course studying the plays of Molière, Racine, and Corneille (in French)—Shakespeare’s 17th-century rivals as leading European playwrights; and a magnificent survey course in Western civilization, whose main textbook I still occasionally consult. My courses in the humanities gave me a lot of deferred gratification. I think that these and similar did a lot to help me comprehend the human condition in its many manifestations.

More generally, I think courses in the humanities tend to make students into better critical thinkers and communicators (especially in writing), shaping them ultimately into more productive persons even in a narrow financial sense. One reason why humanities majors do about as well as ones in the behavioral and social sciences is that a huge proportion (about 40 percent) of them go on for other graduate and professional degrees. Over the years, appearing in scores of courtrooms (as an expert witness), I have encountered many highly successful lawyers who were English or philosophy majors.

Humanities Infiltrated by Woke

If all this is true, why then are humanities enrollments in the doldrums? I think that to a considerable extent, it is because they are dominated by angry, woke persons who have a lot of contempt for the American Dream and American exceptionalism. I suspect college enrollments in general fell over the past decade because a large number of American students, and especially their parents, became increasingly uncomfortable with what was being taught. They do not like when they read about or watch angry university students condemning Israel after the Jews have suffered their worst catastrophe since the Holocaust. Do I want to send my kids or grandkids to study under professors who glorify what I regard as truly verbal excremental filth? Is it no wonder leading law firms have said they will not be hiring graduating students who participated in this morally repulsive behavior!

Meanwhile, as enrollments have plummeted in the humanities—often taught by ultra-progressive faculty—that has not been the case in such areas as engineering or business, where enrollments have generally been relatively robust. Have you ever heard of a woke accounting professor? I suspect they are as rare as Republican sociologists. Wokeness, a significant part of the reason for American collegiate decline, is centered to a considerable degree in the humanities. As a Brown University philosopher professor and writer of some distinction, Felicia Nimue Ackerman, opined recently (in The Wall Street Journal), “[H]ow come many humanities professors are self-important, status-conscious jerks?”

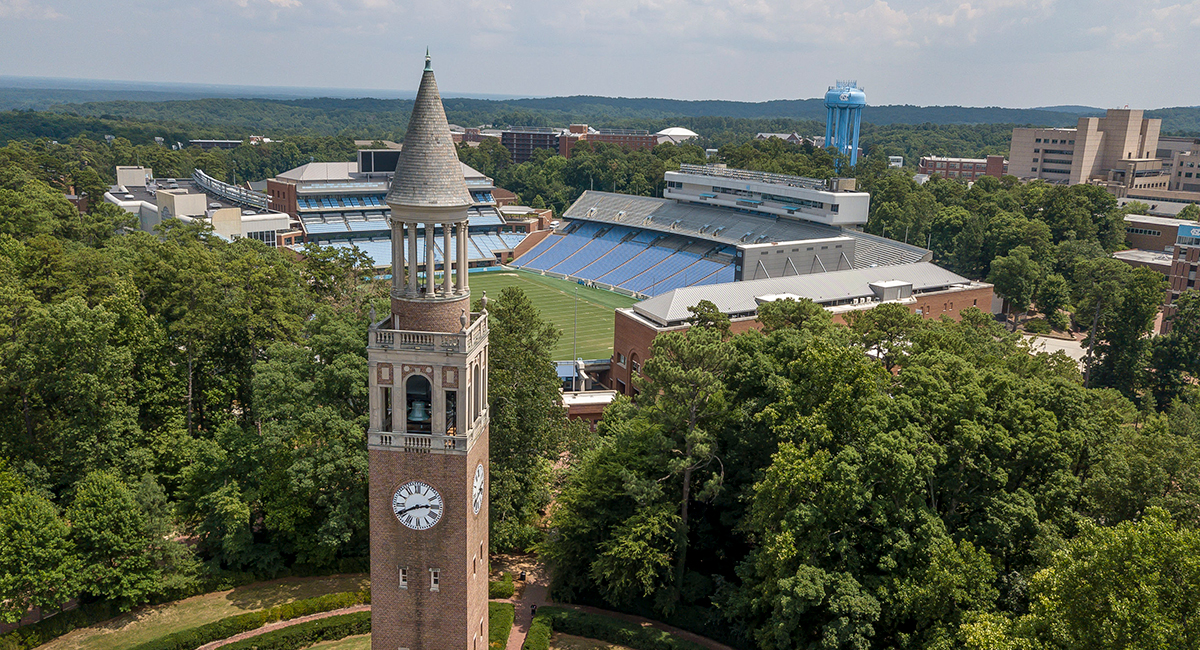

Enrollments have been in decline since 2010 at a large portion of America’s universities, and the 21st-century worldwide aversion to having children suggests that the pool of college-age kids will fall meaningfully in coming years. Financially hard-pressed university presidents will be forced to slash administrative staff supporting the Woke Conspiracy, such as aggressively racist DEI apparatchiks. But they also will find it fiscally necessary and academically appropriate to reduce the number of humanities faculty. Borrowing from John Donne and Ernest Hemingway, the bell is tolling for the woke professors who have done so much to harm the study of the humanities in America.