President Biden and former President Trump have made the same promise to voters: they won’t touch Social Security or Medicare.

That’s not merely disappointing. It’s irresponsible. According to the latest Social Security and Medicare Trustees reports, in the very near future the trust funds supporting these two programs will be depleted. If the president and the Congress do nothing in the interim, the law requires automatic cuts in benefits.

In just eight years, nearly 78 million Medicare beneficiaries will face an automatic 11 percent payment cut in their hospital insurance benefits, and these cuts could come even sooner and strike even deeper if America is hit by a recession. In just ten years, 66 million Social Security beneficiaries will see their monthly benefit checks cut by 23 percent.

That is just the short-term problem. Looking further into the future, the Trustees reports remind us that we have made promises to millions of workers who are paying payroll taxes today, and the future cost of those promises far exceeds the expected revenues dedicated to support them. Further, the gap between future promises and future revenues keeps getting larger through time.

Looking indefinitely into the future, the trustees tell us that the combined promises in both programs exceed expected revenues by $163 trillion. That number is in current dollars and it is an unfunded liability that is almost seven times the size of today’s entire economy.

In a sound retirement system, we would have $163 trillion in the bank earning interest—so the funds would be there to pay the bills as they arise. In fact, we have no money in the bank for future expenses and there is no serious proposal to change that.

So, what can be done?

Hoover Institution economist David Henderson argues that of the two programs, Medicare is the easiest to reform. The reason? Social Security benefits come in the form of cash. Medicare benefits are services in kind. In making his argument, Henderson points to a well-regarded academic finding that Medicaid beneficiaries value enrollment in Medicaid at as little as 20 cents on the dollar. That means that if you offered the enrollees membership in Medicaid or a sum of money equal to a little more than one-fifth of the cost of Medicaid, a great many enrollees would take the money.

Is it possible that the value seniors place on Medicare is similarly much below what Medicare actually costs? If so, there would be an opportunity to spend less on medical benefits, give seniors a cash rebate and lower the taxpayers’ burden—all at the same time.

A mechanism for accomplishing that would be a Health Savings Account, a device that allows younger people to make choices between medical care and other uses of money. A similar account, but with after-tax deposits and tax-free withdrawals (like a Roth IRA) for seniors would avoid the charge that the deposits are a tax dodge. But it would allow seniors to conveniently avoid unneeded care and bank the savings for other purposes.

This is one of a number of ideas proposed in Modernizing Medicare, a multi-authored Johns Hopkins University publication, edited by Heritage Foundation scholar Robert Moffitt and former Heritage vice president Marie Fishpaw.

Of course, in order to give Medicare enrollees the full freedom to choose between health care and other uses of money, seniors would have to have greater choices of plans, and insurers would need greater freedom to offer innovative alternatives.

In one of the chapters, former Congressional Budget Office director Douglas Holtz-Eakin envisions putting Medicare on a budget. Seniors would be given “premium support,” allowing them to buy private insurance of their own choosing. The government’s contribution would grow through time but somewhat more slowly than spending under the current system. Holtz-Eakin estimates that such a reform would save $1.8 trillion in taxpayer costs over 10 years and $333 billion in savings for the beneficiaries.

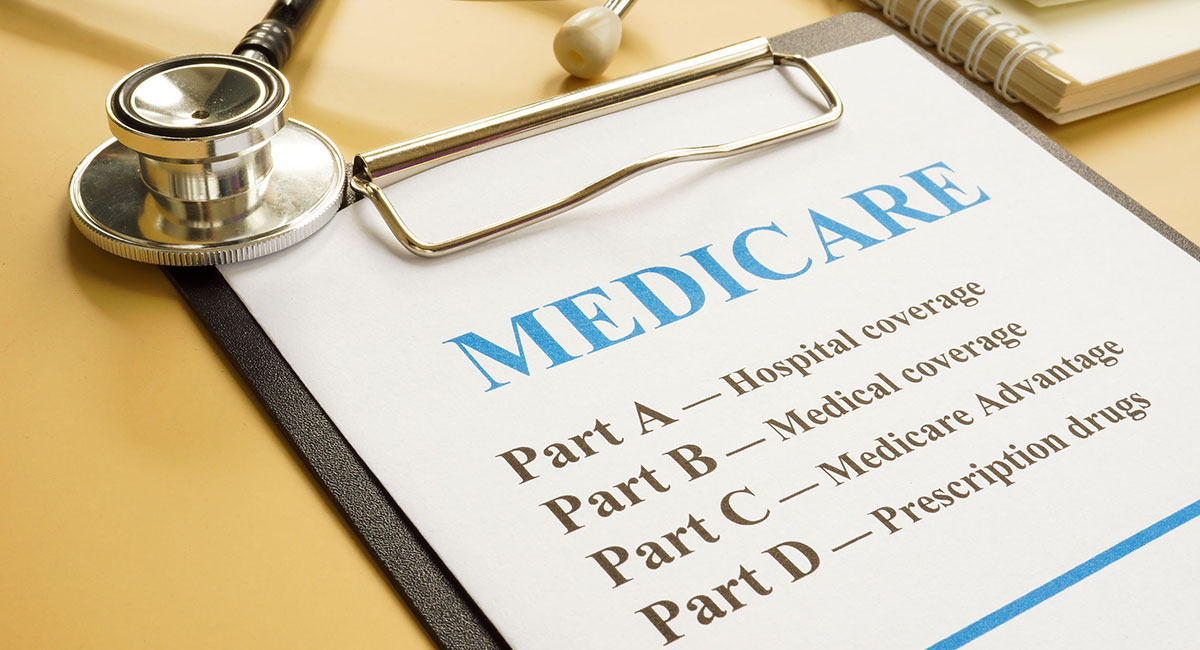

A number of authors point to the Medicare Advantage program, which already enrolls half of all beneficiaries, as the vehicle for change. In this program, seniors enroll in private plans that are similar to the employer-provided plans they had when they were in the work force. Medicare pays for a large share of the cost of the premiums.

American Enterprise Institute economist Joe Antos points out that in the Medicare Advantage program, seniors pay one premium to one plan. By contrast, in traditional Medicare they pay three premiums to three plans: one to Medicare Part B, one to Medicare Part D, and one for Medicap coverage. Antos says traditional Medicare must become more like Medicare Advantage, which saves seniors money and which allows for integrated care—such as combining medical costs and drug costs in the same plan.

In another chapter, former Medicare and Medicaid director Gail Wilensky and Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine professor Brian J. Miller argue that Medicare Advantage should be the default option for enrolling seniors. Right now, if seniors don’t elect a choice, they are automatically enrolled in traditional Medicare. Wilensky and Miller would enroll them in an MA plan instead.

In a chapter by yours truly, I argue for a number of reforms to make Medicare Advantage work better—including continuous open enrollment and the right of return to traditional Medicare.

If the enrollees’ medical conditions change, they should be able to switch to a plan more appropriate for their care. If diabetes emerges, enrollees should be able to switch to a special needs plan specializing in diabetic care. If enrollees develop heart disease, they should be able to switch to a special needs plan for congestive heart failure. No one should have to wait 12 months to enroll in the plan that best meets their medical needs.

Currently, if a senior stays in an MA plan for more than a year and then choses to return to traditional Medicare there can be financial penalties. In all states, Medigap insurers are barred from discrimination on the basis of a health condition when the enrollee first becomes eligible for coverage. But a returnee from an MA plan can be “underwritten” and charged a higher premium if a health condition suggests higher medical costs.

This is wrong, and it is easy to correct. Further, if people know that they can easily return to traditional Medicare when a need arises, that makes enrollment in MA plans more desirable.

These are only a few of the ideas in a book that led to this C-SPAN discussion and should be required reading for every member of Congress.