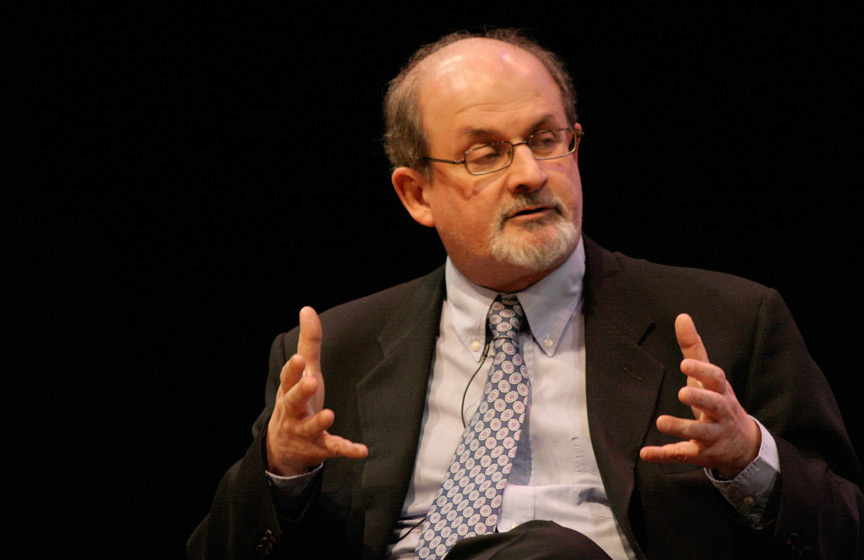

The last time I had the opportunity to talk with Salman Rushdie (four years ago at the Hay Festival of Literature and Arts in Arequipa, Peru), he sounded as if the days of the fatwa—the death sentence issued by Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini in 1989 following publication of Rushdie’s novel, "The Satanic Verses"—were long gone.

He spoke like a liberated man, a condition that on the previous occasions on which we met seemed impossible; after all, some of the previous conversations took place when Rushdie was hiding under the protection of Britain’s Scotland Yard and I was serving as a London-based correspondent.

We now know that he was not free from the Khomeini-imposed death sentence and that, whatever physical condition he is in, he never will be. There will always be a deranged assassin whose fanatical interpretation of Islam makes him believe he will go to heaven if he finishes the job that Hadi Matar did not at the Chautauqua Institution in upstate New York on August 12.

The callous attack should remind us of some important truths. First, that the course of civilization is a tortuous one: Progress has never taken place in a straight line, nor has it occurred uniformly across all geographies, cultures and polities, or across all groups and individuals within a common space.

Barbaric tribalism can coexist with the rule of law and individual rights in any country, and religious obscurantism can thrive alongside secular civilization even as globalization spreads the news and the material benefits of modernity.

When Khomeini’s fatwa was decreed, Hadi Matar, Rushdie’s accused assailant, wasn’t even born. Matar was born and always has lived in the United States, not in an isolated community fed on fanaticism and tribalism, whatever his Lebanon-born parents may have taught him.

In his 24 years, Matar has had ample opportunity to appreciate and embrace the values and institutions that have made the United States one of the most advanced societies in the world, its political and economic problems notwithstanding. And yet, he apparently rejected those values and institutions.

The country of his forebears is itself a good example of the coexistence of secularism and religious obscurantism—of civilization and cultural sophistication, on the one hand, and closed-mindedness and insularity on the other. Once considered the jewel of the Middle East, and rightly so, Lebanon’s state today is partly controlled by Hezbollah, the Shiite terrorist organization, making progress almost impossible.

Another lesson we can take from Rushdie’s tragedy is that literature matters—a comforting thought in today’s world, where social media and many competing forms of story-telling have relegated books to a secondary place, given the short attention span to which entire generations of young people have been reduced.

Of course, literature matters more to Islamist fanatics on the look-out for blasphemous offense than to most other people, but let’s not forget that race-, gender- and other identity-based collectivist attacks on free expression in academia, publishing, media and society-at-large also pose a threat to the arts and civilization in the western world.

Ironically, "The Satanic Verses" is perhaps the worst of Rushdie’s novels (even great writers occasionally write poor literature). It takes the combination of reality and fantasy to far-fetched extremes that detract from the credibility of Rushdie’s tale; its characters seem more fabricated than genuine, and even the satirical elements, including the fictionalized narration of the founding of Islam through the dreams of one of the two main characters, an Indian immigrant in London, fail to produce a suspension of disbelief in the reader.

Khomeini, and before him the hordes of fanatics who in the late 1980s created the climate of intolerance against the book that eventually led to the fatwa, treated literature not as mere entertainment, but something more profound—as all totalitarian societies do and the medieval Catholic Church once did.

Ultimately, the Rushdie affair reminds us that no one who dares write and speak publicly is free from the ire of those who hate freedom. It is the price that writers and public intellectuals have always paid—and will continue to pay.