If you are an economist, it’s hard to be a Democrat these days. The reason: So many Democrats reject economics completely.

Many Democrats appear to believe that if a price is judged too high, the government can simply push it down and nothing bad will happen. If a price is judged too low, the government can push it up. Once again, the presumption is that nothing bad will happen.

These Democrats don’t just reject the idea of a marketplace. They reject the economists’ explanation of how markets work.

Take global warming. Economists are virtually unanimous about how to reduce carbon output: a carbon tax. That’s because of a well-accepted economic proposition: If you tax something, you get less of it. Moreover, you get less carbon in a way that involves the least social cost. As consumers and producers pursue their own self-interests, each will economize on the use of carbon in ways that minimize the cost to them. My colleague, Boston University professor Laurence Kotlikoff, has even calculated the optimal carbon tax, given all that we know at present. It is equivalent to about a tax of 70 cents on a gallon of gasoline.

Although climate change seems to be the No. 1 policy concern for President Joe Biden and most other Democrats, you will have a hard time finding any of them advocating a carbon tax. Instead, the Green New Deal envisions a command-and-control approach—one that would cost six times as much to achieve the same result as a carbon tax, even under the best of circumstances, according to Peter Orszag, an Obama White House adviser and the former director of the Congressional Budget Office. The far Left doesn’t want to solve the problem of climate change by making it in everyone’s self-interest to solve it. Solutions that involve self-interest are viewed as morally suspect.

When economists associate with the Democratic Party, they have one of two choices: They can be silent when the party endorses ideas that no economist could defend, or they can hold their nose and endorse the goals while withholding comment on the means of getting there.

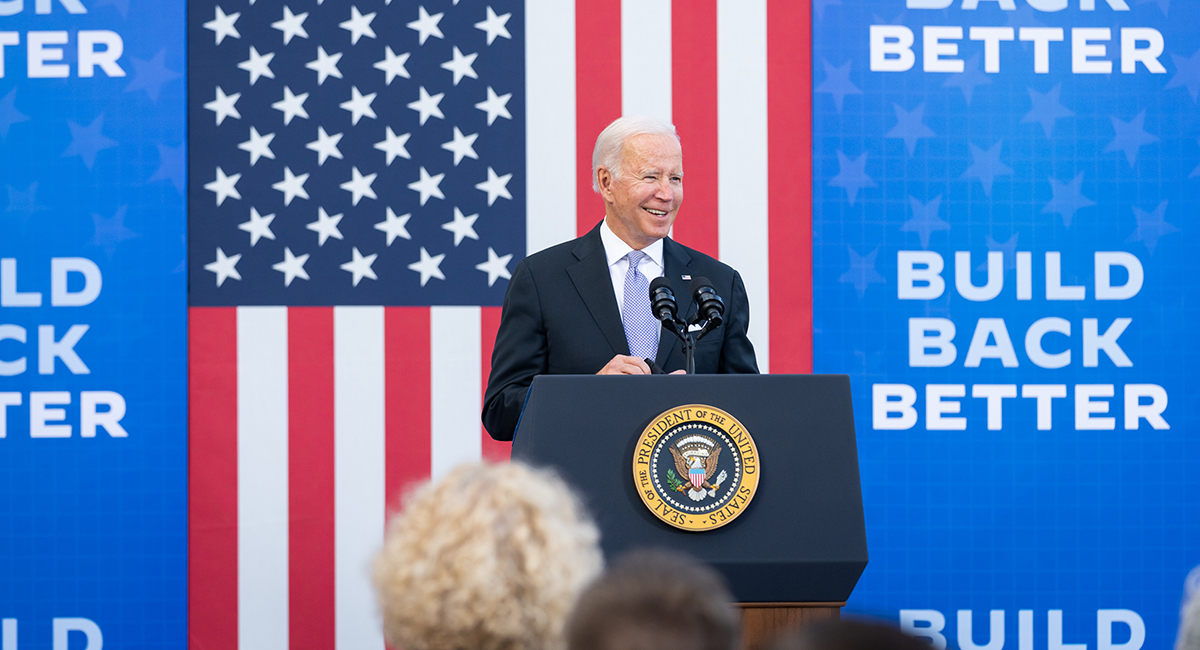

Silence is the normal stance. But as the Wall Street Journal noted in astonishment, 17 Nobel Prize economists signed a letter endorsing the "Build Back Better" proposal—a $5 trillion expansion of the welfare state, with command-and-control climate change reforms thrown in to boot. Even in the unlikely event that the proposal was fully paid for, and thus not inflationary, it would still be bad law. Take two biggies in the proposal: child care and elder home care. At the moment, there has been no widespread reporting of parents leaving small children in the front yard on their way to an 8-to-5 job. Nor do we know of many instances of folks abandoning their disabled parents in similar fashion. In both cases, a great deal of the need is being met by family and extended family.

But let’s suppose we agree it is desirable to give families with small children and disabled parents some relief. What’s the right way to do it?

The most efficient approach would be to give families cash assistance, leaving them free to use the funds in the way that best meets their needs, including paying for hired help. The least efficient approach, and the one included in Build Back Better, is to meet these needs with public-sector workers earning above-market wages and paying dues to public-sector, and Democratic Party-donating, unions.

Bottom line: The Biden administration has been getting a lot of bad advice from economists who should know better.