The recent ABC mini-series, “Women of the Movement,” which the network broadcast on three consecutive Thursday nights in January, introduced Dr. T.R.M. Howard to millions of Americans who had never heard of the late civil rights leader. They deserve to know more.

The series highlighted Mamie Till-Mobley’s search for justice after her son, Emmett Till, a 14-year-old African-American teenager from Chicago, was brutally murdered by two white men while vacationing in Mississippi. During the trial of the killers, Till’s mother stayed in Howard’s home and he provided her an armed escort each day to the courtroom. When the killers were acquitted by the all-white jury, Howard pushed to reopen the case on the grounds that local authorities had suppressed evidence.

Long before Till’s fatal encounter, Howard—who considered himself a disciple of Booker T. Washington—already had become something of a Black folk hero in the Jim Crow-era south.

Born to poverty in 1908 in Murray, Kentucky, Howard’s life exemplified a zealous commitment not only to civil rights, but to the African-American traditions of self-help, entrepreneurship and mutual aid.

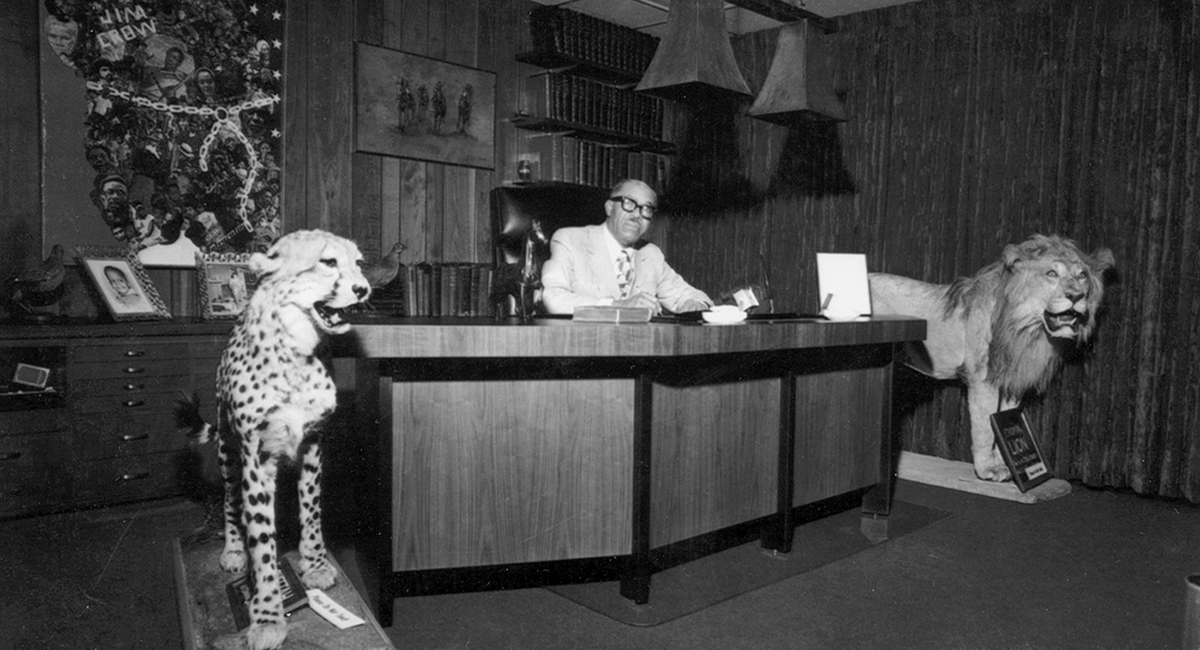

A graduate of Union College in Lincoln, Neb., and the College of Medical Evangelists in California (now Loma Linda University), Howard began his rise to national prominence in 1942 after arriving in the all-Black town of Mound Bayou, Miss., to be chief surgeon at the all-Black Taborian Hospital.The town had been founded in the late 19th century as a beacon of successful Black self-government. In contrast to the rest of Mississippi, African-Americans both voted and held office there. The hospital provided affordable and high-quality health care to the poor without any government aid. By the end of the decade, Howard owned a 1,000-acre plantation, a home construction firm, a restaurant, a small zoo, had founded an insurance company and had built the first public swimming pool for Blacks in the state. Future civil rights icon Medgar Evers (himself a slaying victim, in 1963) got his start while selling insurance for Howard’s Magnolia Mutual Life Insurance Company.

In 1951, Howard founded the Regional Council of Negro Leadership (RCNL), which weaved together an agenda of self-help, mutual aid, thrift, business ownership and voter registration. The RCNL launched a far-reaching boycott of gas stations that denied African-Americans use of their restrooms, distributing an estimated 50,000 bumper stickers with the slogan, “Don’t Buy Gas Where You Can’t Use the Rest Room.” The RCNL picked its target well. As Howard pointed out, African-Americans wielded considerable economic leverage with gas stations because they were nearly as likely as whites to own cars. A typical scenario during the boycott was for Black customers to pull up to the pump, ask to use the restroom, and then drive off if the answer was no.

When the RCNL petitioned school districts to implement the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, it faced its greatest challenge yet. Members of the White Citizens’ Councils, which included many of the South’s business leaders and had been organized to fight desegregation, struck back by systematically refusing loans and other credit to activists. Howard countered this by organizing a nationwide campaign to persuade black organizations and business owners to transfer their deposits to the black-owned Tri-State Bank of Memphis, where he served on the board of directors. Tri-State was then able to provide the loans, reducing the impact of the Citizen Council “credit freeze.”

The extraordinary impact of T.R.M. Howard goes far beyond the heroic efforts depicted in “Women of the Movement.” His entire adult life illustrated how self-reliance and business success go hand-in-hand with civil rights. He was a determined advocate of non-violence, but stressed that African-Americans have the constitutional right to defend themselves when their lives and liberty are under attack, even with guns, if necessary.

As Medgar Evers’ widow, Myrlie, put it: “One look told you that he was a leader: kind, affluent and intelligent, that rare Negro in Mississippi who had somehow beaten the system.” In our current toxic political environment, his story should serve as an inspiration for every American.