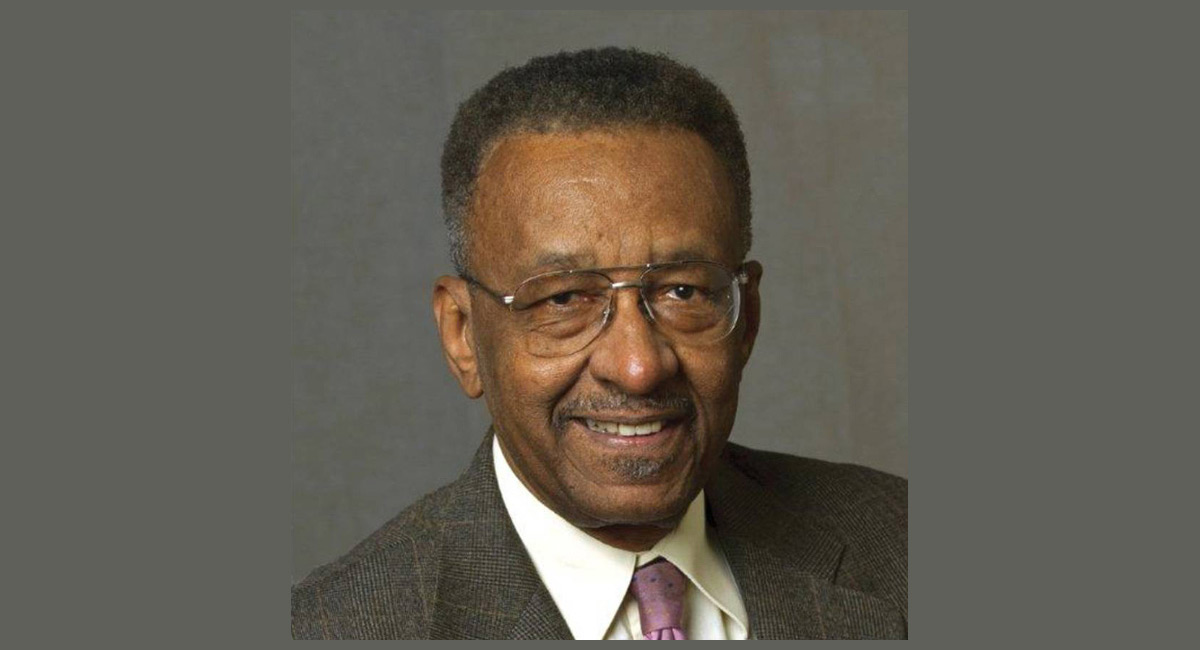

The world lost an intellectual giant this week when the economist Walter E. Williams passed away. Williams was the John M. Olin Distinguished Professor of Economics at George Mason University, an economist’s economist, a scholar’s scholar, and an unparalleled communicator of economic wisdom and ideas. He loved liberty, defended it eloquently, and went to great lengths to show how good intentions don’t readily translate into good outcomes.

Williams’s work and commentary was informed by a deep understanding of how free people in free markets find ways to help one another. Howard Baetjer explains the “Invisible Hand Principle” in his short book Economics and Free Markets. He quotes Williams, who said “In a free market, you get more for yourself by serving your fellow man. You don’t have to care about him! Just serve him.”

We get, as Adam Smith explained, what we want by helping other people get what they want. Importantly, this requires us to respect their right to say “no.” Free markets rest on a profound respect for others’ dignity. A free market is possible and productive when we recognize that other people are not merely means to our ends, created to serve us or created to live as we want them to. If we want to secure their cooperation, we have to give them what they want rather than what we think is best for them. Few people understood this better than Walter Williams.

I tell my students that I don’t want to retire. I basically want to die at my desk at the end of a long and fruitful life. Williams embodied that dream, and he was a scholar and an educator to the end: he taught his final class on Tuesday and passed away on Wednesday—the same day his final syndicated column appeared.

In a touching tribute in the Wall Street Journal, his longtime colleague Donald J. Boudreaux writes,

“The economics profession boasts many excellent minds, but it has precious few with the ability and interest to do rigorous research and to engage the public with its results. Milton Friedman was such a scholar, as is Thomas Sowell. Walter was in their league.”

Some of my proudest moments as a teacher have come from hearing how my former students did in the microeconomics course he taught to PhD students at George Mason University. I knew they were in better hands than mine with Walter E. Williams, and I knew that if they were performing well in his course, it was because they really knew their stuff.

His PBS video series Good Intentions was based on his 1982 book The State Against Blacks, which is fortunately available on YouTube. The dates have changed, but the logic and the lessons have not.

Williams was a towering intellect who made the economic way of thinking come alive to generations of undergraduates, graduate students, readers, and anyone who would listen. He suffered no fools, which incidentally appears as the title of the 2014 Free to Choose Network documentary on his life and work. To adapt an African proverb, the best time to start reading Walter Williams’ work is twenty years ago. The second best time is right now.

Farewell and Rest in Peace, Dr. Williams. Your shoes will be impossible to fill.