Today, the adjective “fascist” is an epithet—often mixed promiscuously with “white supremacist,” “sexist,” etc.—that the ruling class uses to besmirch whoever challenges them, and to provide emotional fuel for cowering, marginalizing, and disempowering conservatives.

This maneuver consists of defining fascism in terms of unpopular ideas, political practices, and personality traits observable in many times and places; then, having cited Hitler’s Nazi movement as fascism’s quintessence, of pinning those deplorable characteristics on the intended targets. This reductio ad Hitlerum aims at no less than to outlaw conservatives. As the Washington Post’s Jennifer Rubin exclaimed: “these people are not fit for polite society.... I think it’s absolutely abhorrent that any institution of higher learning, any news organization, or any entertainment organization that has a news outlet would hire these people.” And the New Republic explains “why fascist rhetoric needs to be excluded from public discourse.” The establishment doesn’t seem to realize that they are preaching some of fascism’s practices.

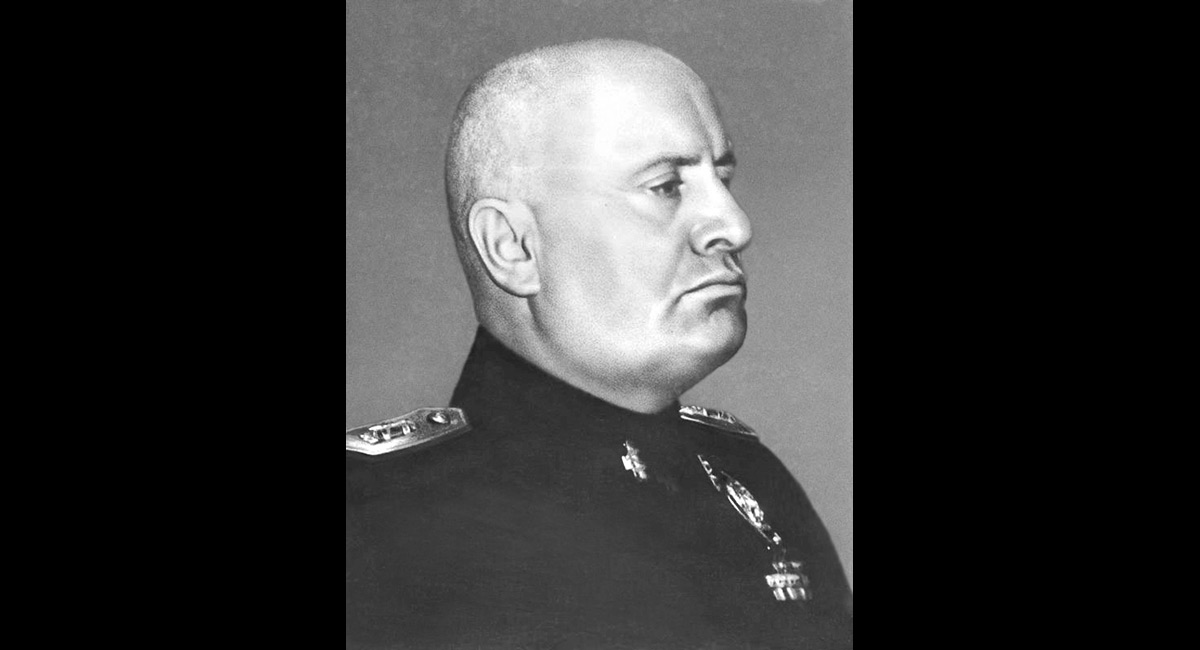

This essay looks behind fighting words to fascism’s reality. Although Benito Mussolini, fascism’s artificer and personifier, died discredited in 1945, fascism’s socio-political paradigm, the administrative state, is well-nigh universal in our time. And as the European and American ruling class adopted Communism’s intellectual categories and political language, the adjective “fascist” became a weapon in its arsenal.

We begin with how fascism developed in Mussolini’s mind and praxis from 1915 to 1935, how it was hardly out of tune with what was happening in the rest of the Western world, as well as how it then changed and died. After considering how fascism fit in the 20th century’s political warfare doctrines, we explore its place in contemporary political struggles.

Rising Star

Mussolini was radical, talented, ambitious, insatiable. He fashioned fascism out of the ideas and circumstances of his time.

In 1883, his socialist father, a blacksmith, named him for the most radical revolutionary of the time, the Mexican Benito Juárez. His middle names were those of Italy’s most radical socialists. But Benito was also raised to revere the liberal republicans who had unified Italy. Outstanding as a student, the boy qualified to teach in secondary education upon his own secondary-school graduation. Since age 18, he carried the official title “professor.” But teaching in small towns strained his leftist political advocacy and his personal ambitions, including sexual ones. He was a “chick magnet.” Also because he was not about to let himself be drafted into the king’s army, he emigrated to Switzerland in 1902.

While supporting himself as a stonemason, he learned German and French, studied philosophy, in part at the University of Lausanne. He read Friedrich Nietzsche, Charles Péguy, Georges Sorel, Arthur Schopenhauer, Immanuel Kant, G.W.F. Hegel, and Karl Marx, among others. He was active in socialist circles, both Italian and international, giving speeches to workers and helping to organize strikes—which got him expelled. He got to know Vladimir Lenin, who later chastised Italian socialists for letting such a talent leave their ranks.

Back in Italy, taking advantage of an amnesty for having evaded the draft, he served for two years in the army’s elite Bersaglieri corps. After two more years of teaching, the 26-year-old Benito became a full-time socialist activist, first in Trento—at the time part of Austria—where he agitated for national reunification as editor of its socialist newspaper. Back home, he supported himself writing essays and editing a journal called Lotta di classe—class struggle—and even writing a savagely anti-clerical novel. In 1911 the party entrusted the 28-year-old with editorship of its flagship publication, Avanti!. He quintupled its circulation. In 1913 he published his only non-fiction book, Giovanni Huss, il veridico in praise of John Hus, the 15th-century Czech religious reformer. By 1915 he had also married, and fathered a son by one of his mistresses. He had become Italian socialism’s brightest star.

The socialist movement’s adherence to Karl Marx’s dictum “the workers have no fatherland” had led to the expectation that the masses would not lend themselves to war among nations, and is among the reasons why many believed that the Great War would not happen. But when it did, rank-and-file socialists in all nations dragged all but fragments of their respective parties to support the carnage. So long as Italy stayed out of the war, Italy’s socialist party was the major exception, along with Russia’s Bolshevik faction. In 1911, Mussolini had campaigned against Italy’s war in Libya. In August 1914 he wrote a fiery editorial, “Abbasso la guerra!”: Down with the war! By November, however, he was arguing that entering the war would complete Italy’s unification by taking the Austro-Hungarian empire’s Italian-speaking regions, and make possible a host of beneficial social changes. He gave up his editorship and started another newspaper, Il Popolo d’ Italia, the Italian people.

In December, he committed socialist heresy by writing that class struggle is a bad idea because the nation is more important than social class. He called his few scattered followers fasci, bundles, of individuals. The word recalled the bundles of punishing rods and axes that ancient Rome’s lictors bore for the consuls. Hence he labeled the movement “Fasci Rivoluzionari d’Azione Internazionalista” and its members “Fascisti.” In 1915, when Italy entered the war, as most of the party remained faithful to doctrine, and as Mussolini further identified with popular sentiment, the party expelled him and his Fascisti and did its best forcibly to silence them. Mussolini joined the army, served honorably, was wounded and discharged, while continuing to call himself a socialist and propagandizing his evolving blend of nationalism and socialism. Military service bound him more closely to ex-soldiers than he had ever been bound to socialist comrades.

Mussolini’s description of fascism’s first formal gathering, in Milan in 1919, when the movement counted only 200 members, reflects pragmatism rather than ideology. The fascist movement, he said, is “a group of people who join together for a time to accomplish certain ends.” “It is about helping any proletarian groups who want to harmonize defense of their class with the national interest.” “We are not, a priori, for class struggle or for class-cooperation. Either may be necessary for the nation according to circumstances.” Notice the primordial emphasis on “nation.”

Throughout 1920, those circumstances dictated focus on the main domestic and international issues of the day: the extent of labor’s influence in the economy and the extension of Italian sovereignty over the Adriatic Sea’s eastern shore. Mussolini’s pronouncement on the former—some kind of legal “representation of labor”—evolved into the core of fascist domestic policy. Insistence à outrance on Italian expansion became its foreign policy. With regard to the choice between monarchy and republic, Mussolini confessed a bias for republicanism, but so sought the approval of monarchists that he was willing to bow to the reality of monarchy. He denounced the new Lenin regime’s barbarities in the strongest language. Fascists would fight to the death to save Italy from such a lawless violence.

Seizing Power

In 1921, Mussolini shifted to building fascism into a party. It helped, he said, that persons insufficiently in tune with fascism were leaving its ranks, first the “Wilsonian idealists,” then those who “could not burn their bridges to other parties, and then those insufficiently committed to socioeconomic restructuring.” By year’s end, he had sketched the formula by which he sought adherents and legitimacy: “to love, each day more fully, this adorable mother of ours, Italy.”

The war, and his own military service, had impressed upon him of what human beings are capable when acting as a disciplined mass. All over the world, people had produced more things, made greater sacrifices for their countries, than anyone had thought possible. European elites had been worshiping the state’s architectonic powers since the time of Louis XIV’s ministers (Louvois, Vauban, Colbert). G.W.F. Hegel, following Napoleon, had made patriotic worship of the scientifically administered, progressive state the political essence of modernity. Mussolini’s vision of Italy followed from that. “The bureaucracy is the state,” he said.

“When the nation’s interests are at stake,” Mussolini explained, “all particular interests, whether the proletariat’s or the bourgeoisie’s, must be silent.” “All know that Benito Mussolini is an individualist,” he declared. But, as regards the nation, “[Mussolini] is utterly disciplined.” The state personifies the country, and disciplines its several elements to its service. “Soon, we will be the state.” “We do the bureaucracy the highest honor and raise it to a level above that which it occupied under previous governments by making it into an army of co-belligerents, which works toward the same end.” He said that Catholicism too must be brought into the nation’s service in order to revive the Italian people’s millennial tradition of greatness. Doing all this would take sacrifice, perhaps war, as had the struggle for independence in the previous century, and as the Great War had reawakened national consciousness.

By year’s end, fascism was personified by thousands of street warriors who cheered their “Duce” (Leader), and who seemed to live the poet Gabriele D’ Annunzio’s exalted patriotic visions.

Mussolini, however, felt the need to explain himself philosophically. He called himself “a practical relativist.” In contrast with Germany, he said, where relativism is a “most audacious, destructive theoretical construct, in Italy [thanks to fascism] it is but a fact.” “That is because fascism never tried to define its powerful, complex spirit definitively, but rather proceeded ad hoc by intuition...[that is why] we, from time to time, can call ourselves aristocratic and democratic, revolutionaries and reactionaries, proletarians and anti-proletarians, pacifists and antipacifists. We are truly relativists par excellence.” “Relativism is akin to Nietzsche’s Der Wille zur Macht, and fascism is a most formidable creature of an individual and collective will to power.”

Because Italy’s parliament had been elected according to proportional representation, the government consisted of a coalition of parties. The king appointed the prime minister, who would form a majority coalition. Membership in the government depended on intra-party deals. In the 1921 elections, Mussolini’s Fascists had gained only .04% of the vote. But chaos reigned in the streets because of socialist, Communist, and anarchist mobs, as well as because of the perhaps 40,000 fascist squadristi (the Blackshirts) who fought them. The government seemed irrelevant. King Victor Emmanuel III and the rest of the country looked for a savior. Mussolini organized the descent of some 30,000 squadristi on Rome to demand he be named prime minister. The incumbent, Luigi Facta, demanded the king institute martial law. When the king refused, Facta resigned and the king appointed Mussolini to head a government with almost no fascists. But, beginning with parliament’s grant of plenary powers for a year (recalling the Roman institution of constitutional dictatorship), Mussolini gradually dispossessed the rest.

Hegel, as well as the positivist and Progressive movements, had argued for the sovereignty of expert administrators. Fascist Italy was the first country in which the elected legislature gave up its essential powers to the executive, thus abandoning the principle, first enshrined in the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution, by which people are rightly governed only through laws made by elected representatives. By the outbreak of World War II, most Western countries’ legislatures—the U.S. Congress included—had granted the executive something like “full powers,” each by its own path, thus establishing the modern administrative state.

His Word Was Law

Upon receiving full powers, Mussolini dissolved the king’s guard, creating instead a “Volunteer National Security Militia” within the armed forces, composed of his faithful street fighters, thenceforth “armed by the government and ready to defend it even with their blood.” Having shunted aside the parliament, he substituted the “Fascist [Party’s] Great Council,” to which he made his tenure as prime minister formally responsible. (Twenty years later, though, this formality turned out to be the legal vehicle by which Victor Emmanuel was able to depose Mussolini.) The Catholic Center Party noticed Mussolini’s disregard for limits, that the new government’s character was “anti-parliamentary, anti-democratic, anti-liberal,” and that it was entirely partisan. To render their and others’ exit from the government inevitable, Mussolini “exasperated” the contrast. By 1926, his word was law.

In 1924 Mussolini had described that law’s spirit in a commentary on Machiavelli. For him, The Prince was “the statesman’s handbook” because “neither men nor states have changed.” “While individuals, impelled by their selfishness, tend to social dissonance, the state, by nature, is organization and limitation.” Mussolini’s article “force and consensus” was a gloss on what he called Machiavelli’s essential teaching: “all armed prophets won, and the unarmed ones came to ruin.... Because the nature of peoples is variable, and it is easy to persuade them of things, but difficult to keep them thus persuaded. Hence one must make sure that, when they no longer believe, one may be able then to force them to believe.”

Rather than force, Mussolini’s primary means of government was the management of interests. That, plus exhortation. Force was reserved for outright opponents in the act of opposition. The kidnapping and murder of socialist member of parliament Giacomo Matteotti at the hand of fascists is so often mentioned precisely because it was such a rarity. The socialists and Communists who wished to continue in politics had to leave the country—the Communists to Russia, where Palmiro Togliatti headed Stalin’s Comintern, and the socialists mainly to France. Of the ones who stayed the most outstanding, like the Communist Antonio Gramsci (who had been socialism’s other intellectual star), got prison sentences during which they were free to write. The lesser ones were forced to keep their activism to family and friends lest they be beaten and forced to swallow laxatives. Murderous legal force was reserved for the mafia. A wave of extra-judicial killings, tortures, as well as the practice of using families as hostages and for reprisals largely extirpated the “black hand,” or forced its members to seek refuge in America.

Socioeconomic organization was fascism’s defining feature. Only employers’ and employees’ organizations approved by the government were allowed. They represented and collected dues from any and all in their category and territory, whether these had signed up with them or not. In 1925 these had agreed “voluntarily” to recognize each other as “exclusive representatives,” to subordinate interactions at the local level to central organizations, and to draw up procedures for their cooperation under government supervision. The Law of Corporations of April 3, 1926, codified this political-economic order. No longer would corporations be responsible to owners. Thenceforth, they would answer to higher duties as defined in the law. As Mussolini put it, “In a world of social and economic interdependence...the watchword must be cooperation or misery.” “Labor and capital have the same rights and duties. Both must cooperate, and their disputes are regulated by law and decided by courts, which punish any violation.” This resulted in the orderly servicing of interest groups, fascism’s daily preoccupation.

Mussolini’s favorites, other than the military, were teachers, to whom he gave repeated, rousing praise and exhortation. Nationalism notwithstanding, he also courted Italians’ ingrained localism. Having substituted appointed for elected municipal authorities, he tried to fill the positions with local icons. For nearly all Italians, life in the late 1920s and ’30s was better than it had ever been. The generation just after World War II grew up amidst stories about the wonders of life “before the war.”

Mussolini’s 1929 concordat with the Roman Catholic Church, by far the country’s most influential element, was the culmination of his dealings with established interests. Under that arrangement, the pope recognized Italy’s sovereignty and Rome as its capital. Though the pope continued to appoint and remove bishops, these would swear allegiance to the state. The state recognized the pope’s independence and sovereignty over the Vatican, and Catholicism as the state religion. The state paid the priests. The Church administered religious instruction in public schools. This was a pact between alien forces whose best alternative was non-aggression. More than anything else, their mutual blessing defined daily life under fascism for most Italians.

Because commentary, as often willful as ignorant, confuses fascism and Nazism, we must observe that the concordat’s other party, Pope Pius XI (1922–1939), knew Germany as well as Italy intimately, and was Nazism’s first, most consistent, and arguably most feared enemy. In 1937 Pius XI wrote a fiery anti-Nazi encyclical, in German, Mit brennender Sorge (With Burning Anxiety), and ordered that it be read in every parish church. He organized opposition to Hitler. This most fervent of anti-Nazis died before Mussolini fully changed the regime for the sake of the German alliance. The pope condemned fascism’s racial laws of 1938 in the strongest possible terms: “I am ashamed of being Italian.” “For Christians, taking any part in antisemitism is forbidden. We are spiritually semitic.” He and his successor, Pius XII, did all in their power to subvert these laws. But he never compared them with Germany’s, or fascism with Nazism, because, while the former aimed at separation, the latter aimed at extinction.

Next to keeping power, Mussolini’s principal task was to lead Lombards and Sicilians, Venetians, Romans, and Neapolitans—some of whom spoke mutually unintelligible dialects, who looked different, had different habits, and who generally did not like each other—to feel part of the same nation. Speeches exalting Rome’s glory helped a little. Truculence toward Britain and France, especially as regards colonies, helped some more. Mussolini believed that making Italy a colonial power would help even more. He waged war on Libya ruthlessly.

America the Beautiful

The United States of America was the nation of which Mussolini spoke with the highest regard and with which he most assiduously cultivated relations, perhaps because, in the minds of the millions of Italians whose friends and relatives had emigrated there, the very word “America” was synonymous with all good things. Did he really mean that “the American government is more like the fascist state than any of Europe’s liberal democratic governments because the popular will is constitutionally circumscribed”? “Both nations,” he declared, “are young, full of faith in themselves and committed to becoming prosperous and strong. The American people must sympathize with our need for cultural and economic expansion because they are spreading their own economic empire over the whole world.”

After Franklin Roosevelt’s inauguration in 1933, Mussolini’s enthusiasm for likening the New Deal to fascism’s political-economic order was tempered only by the need not to give additional ammunition to FDR’s domestic opponents, who were saying precisely that. Yet, ab initio, he made clear that “the spirit of [FDR’s program] resembles fascism’s since, having recognized that the state is responsible for the people’s economic well-being, it no longer allows economic forces to run according to their own nature.” Mussolini also published a glowing review of U.S. Agriculture Secretary (eventually Vice President) Henry Wallace’s 1934 book, New Frontiers. Fascists rejoiced that FDR had forsaken liberal for corporativist principles, and that the world’s most powerful country, the country most admired by Italians, had taken the trail they had blazed.

The good feeling was largely mutual—until 1935. Even prior to Roosevelt’s New Deal, American statesmen and elite journalists regarded fascism and Mussolini as interesting, and perhaps imitable, examples of how to deal with the post-war period’s challenges.

The view that the New Deal was “fascism without the billy clubs” was well-nigh universal among FDR’s opponents on the Left (e.g. Norman Thomas), as well as on the Right (Herbert Hoover). It could hardly have been otherwise since the essence of the National Industrial Recovery Act—the involuntary inclusion of all participants in categories of economic activity and their subjection to government-dictated prices, wages, and working conditions—was at least as detailed as those in fascism’s corporate law. The U.S. government had brushed aside the Supreme Court’s objections to the National Recovery Administration in A.L.A. Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States (1935). By 1942, in Wickard v. Filburn (still “good law” today), the Court approved regulation of all manner of enterprise with reasoning stricter than any Mussolini had used in 1926. Today, by the same token, Senator and 2020 presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren’s proposed “Accountable Capitalism Act” would also force corporations to enroll into a legal scheme in which the government would force them to service various stakeholders as government regulators would decide from time to time. Such tools are far more powerful than billy clubs.

Until 1935 New Dealers, though careful not to add to their opponents’ ammunition, did not hide their administration’s kinship with what the Fascists, Nazis, and Communists were doing to redirect the societies over which they ruled. Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes thought that “what we are doing in this country is analogous to what is being done in Russia and even under Hitler in Germany. The only thing is that we do it methodically.” FDR himself referred to Mussolini and Stalin as “blood brothers,” and spoke of having private contacts with Mussolini. “Mussolini,” he said, “is interested in what we are doing, and I am struck by how much of his doubtless honest programs to reform Italy he has accomplished.” Brain-truster Rexford Tugwell thought that the fascists had done

many of the things which seem necessary to me. At any rate, Italy has been rebuilt materially in a systematic manner. Mussolini has the same opponents as FDR, but he controls the press, which prevents them from daily spreading their nonsense. He governs a compact, disciplined country, despite insufficient resources. At least on the surface, he has achieved enormous progress.

In the New York Times, Isaac F. Marcosson compared Mussolini to Theodore Roosevelt. Lincoln Steffens, arguably the most progressive of journalists, saw the same resemblance.

In a 2016 article for the Conversation, an online academic journal, historian John Broich best summed up how fascism and il Duce were viewed in the U.S.: “Mussolini was a darling of the American press, appearing in at least 150 articles from 1925–1932, most neutral, bemused or positive in tone.” The Saturday Evening Post even serialized the fascist leader’s autobiography in 1928. Acknowledging that the new “Fascisti movement” was a bit “rough in its methods,” as the New York Tribune put it, papers ranging from the Cleveland Plain Dealer to the Chicago Tribune credited it with saving Italy from the far Left and revitalizing its economy. From their perspective, the post-war surge of anti-capitalism in Europe was a vastly worse threat than fascism. Ironically, while the media acknowledged that fascism was a new “experiment,” papers like the New York Times commonly credited it with returning turbulent Italy to what it called “normalcy.” In 1933, when Hitler came to power, the press and public opinion gave him a pass for about a half decade by treating him as “the German Mussolini.” Not so.

The Beginning of the End

Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia, and Britain’s reaction to it, started the chain of events that led to World War II in Europe and, incidentally, to Mussolini’s own deservedly grotesque end.

Overheated rhetoric had not blinded Mussolini to Italian geopolitics’ principal fact: as ever, Italy’s independence depended on keeping the Germans at bay. Hence, whatever else the Versailles settlement had done after the Great War, its weakening of an Austria separate from Germany had served Italy well. Italians, not pleased at Hitler’s rise on a platform of pan-Germanism, and worried that Austria was friendly to it, had cheered Mussolini’s alignment with Britain and France in a pact to sustain Austria’s independence, signed at Stresa, on Italy’s Lake Maggiore, two hours by rail from the Brenner Pass. Geographically, Italy was the sine qua non of support for landlocked Austria’s independence—which independence guaranteed its own. But in 1935, everybody forgot all that.

Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia, another member of the League of Nations, exposed the League’s nonsense. Britain could have stopped the invasion by closing the Suez Canal to Italian shipping. This would not have avoided the consequences of alienating Italy, but it would have saved Ethiopia. Or, Britain could have sacrificed Ethiopia and the League for the sake of appeasing Mussolini in order to stop Hitler’s Anschluss of Austria. Instead, Britain and France doomed Ethiopia by keeping the canal open, and alienated Italy by instituting energy sanctions. The Italo-British interactions of 1935 might qualify as the 20th century’s dumbest, most tragic diplomatic démarche. Hitler was the only winner.

Seeing his chance, the Führer sent trainloads of coal to alleviate Italy’s energy shortage. A year earlier, as the two dictators had approached each other for their first meeting, Mussolini had said to his foreign minister, “non mi piace”: I don’t like the looks of him. For him, Hitler was semi-literate, and Nazi ideology, especially their racialism, was “boring and pretentious.” Moreover, the Germans had been “illiterate when Rome had Caesar, Virgil, and Augustus.” Now, Mussolini, stupidly grateful, guaranteed the Anschluss by throwing away the Stresa pact. Thus did he commit one of Machiavelli’s most prominent no-nos: putting his future in the hands of a power greater than his own.

Within five years, Charles de Gaulle aptly described Mussolini as riding a donkey behind Hitler’s war horse. Mussolini had secured the Catholic Church’s support. He had the finest relations with America. But, subsequent to his turn to Hitler, the Church de-legitimized and subverted him, and the Italian people found themselves at war against the country they admired most on behalf of the one they liked least. He ended up alienating even the Fascist Party.

“The race question in Italy” he said in 1938, “must be treated from a purely biological standpoint, without philosophical or religious implications. Our racism must be essentially Italian, and its direction nordic/Aryan.” “There is a pure Italian race.” “The Jews do not belong to the Italian race.” “The Italian people’s physical and psychological characteristics must not be allowed to change.” Acting on these principles, the regime forbade marriages between Jews and Aryans, forbade Jews from hiring Aryan domestic servants, forbade Jews from working for the government or for banks or insurance companies or to be professors in public schools, restricted Jews to very small businesses and farms, and forbade the entry of Jews into Italy. Jewish children were forbidden from public schools, except in places where there were not enough to provide separate schools for them.

Speculating on the motivation behind these laws is useless. The stated aim, convincing Italians that they all belong to a single race—albeit a branch of the alleged Aryan race—cut against reality. There is no such thing as an Italian race. Italians in different regions had never heard of Aryans and believed they were racially different from one another. But in all regions, Jews were physically indistinguishable, and respected. If there were “races” of foreigners whom Italians generally disliked, it was the Germans, followed by the Serbs and Croats.

But so foreign to Italians were these strictures that they were largely evaded, starting at the top. Mussolini’s mistress of longest duration, episodically since 1911, was the Jewish author Margherita Sarfatti. Francesco Turchi, editor of the main fascist newspaper, was one of countless notable fascists who subverted the racial laws. Charged in the post-war period for his prominent role in the party, all charges were dropped when a crowd of Jews whose lives he had saved from the Germans showed up at his trial. Any number of other high-ranking fascists helped provide baptismal certificates or otherwise smuggle Jews into the custody of the Church. Ordinary Italians, accustomed to evading laws, paid even less attention to these. Jewish refugees from the rest of Europe in transit to Spain and Portugal (the safest, most welcoming places in Europe for Jews) or to America, got winks, nods, and help.

Downfall

The war destroyed what remained of Mussolini’s legitimacy and of his judgment, as well as his health. Circa November 1942, members of the military high command, as well as some high-ranking members of the Fascist Party began to press King Victor Emmanuel to depose him and get Italy out of the war. On July 10, 1943, Italians greeted the U.S. invasion of Sicily joyfully. This moved the king to tell former foreign minister Dino Grandi that, should the Fascist Grand Council recommend Mussolini’s removal, he would be willing to use his constitutional powers to appoint a successor. The debate on July 24-25 that preceded the Council’s vote of confidence in Mussolini was about the national interest, not ideology. After the vote, the king ordered Mussolini’s arrest.

His successor, Pietro Badoglio, a career army officer, tried to arrange an immediate switch of allegiances to the Allies. Had this happened suddenly, even as Italian troops were enmeshed with the Germans, these would have been unable to organize a defense against the Allied advance. But Soviet influence in the Allied councils dragged out Supreme Allied Commander Dwight Eisenhower’s acceptance until September 3, by which time the Germans were ready to arrest Italian troops (some 815,000 became German prisoners of war). Germany also invaded northern Italy, rescued Mussolini from the king, transferred him to their occupied zone, and used him as a puppet until the end of the war. Mussolini ruled northern Italy for a year and a half as Hitler’s bloody agent.

In April 1945, when Communist partisans executed Mussolini and hung his body upside-down from a meat hook in a Milan gas station, there was some pity, but no regrets.

But the fascist state’s legacy proved durable. Fascism had fathered the modern administrative state’s omnicompetent bureaucracy. The state had a monopoly on a variety of goods, including salt, tobacco, saffron, and telecommunications. Fascism had invented public-private partnerships and “para-state corporations” in all manner of enterprise. It had established a state-run movie industry, and so forth. Just as important, fascism had habituated Italian politicians to think of power in fascist terms—in terms of control of all that bureaucratic power and patronage. The Communists, understandably, wanted that power. But none of the other contenders in 1945 seemed interested in passing up the gigantic opportunities for political patronage that stewardship of the orphaned fascist state offered.

The U.S. occupation, eager to return responsibility to Italians for their own affairs, and confronted with multiple political parties clamoring for power, turned matters over to a consortium of parties that, rather than dismantling the fascist state, parceled its contents out amongst themselves. All subsequent political struggles into our time, regardless of the personalities and ideologies involved, have been quarrels about pieces of this patronage. In our time, Italy’s government appoints some 700 persons per year to very high-paying, powerful positions in “private” companies strictly on the basis of the relative weight of the parties in the governing coalition. That is in addition to the clearly public posts and sinecures it fills. Fascism lives!

Nevertheless, a little attention is enough to separate Italy’s fascism up to 1935 from Hitler’s National Socialism. Whereas the former understood itself as bound by Italy’s characteristics going back to Roman times, as well as by the Church, and aiming at concrete improvements in the lives of Italians, Nazism was always a purely revolutionary movement, hostile to Germany’s history, reality, and welfare. The race that it purported to represent was a myth that abstracted from real Germans. Nazism’s gods were its own invention. Hitler’s last statement may have been his most telling: “The German people were not worthy of me.” That is not nationalism. The Nazis never called themselves fascist. The fascists wanted a place in the sun for Italy. The Nazis acted as if they were the sun.

Neither was General Francisco Franco’s regime in Spain fascist. Authoritarian rule is not the same as fascism. No regime in Europe was friendlier to Jews. There was not an ideological bone in Franco’s body. He had entered politics in 1936 to command one side of a civil war and, until his death in 1975, was all about extending the peace his side had won against a part of the population which would have restarted the war and that seems to revel in its bitterness even today. While Franco’s Spain was officially neutral in World War II, no single act contributed more to Hitler’s defeat, at a more perilous time, than did Franco’s refusal to let the Wehrmacht attack Gibraltar from the rear in July 1940.

Nor was the regime of Portugal’s António de Oliveira Salazar (1932–1968) ideological, much less fascist. He denounced fascism as “pagan Ceasarism.” A Catholic, professional economist, and finance minister, Salazar enforced old-fashioned conservatism on a population that otherwise might have succumbed to the civil war that well-nigh destroyed nearby Spain. In World War II, Salazar’s Portugal was openly neutral on the side of the Allies.

In Hungary, the Communist Béla Kun declared a Soviet Republic in March 1919—the only instance outside of Russia where Communists actually ruled. Executions and all manner of outrages followed. The right-wing regime that overthrew it and reigned in Hungary from 1920 to 1945 under the regency of Admiral Miklós Horthy took vengeance against the Communists and whoever might have supported them, prominently the Jews. But, until Germany effectively took over, the regency’s several governments did their ghastly deeds pursuant to elections, and under parliamentary authority. Nor does it make any sense to ascribe any ideology to them.

Any realistic notion that fascism was something that transcended Italy should have been put to rest in 1934 at a conference on “International Fascism” held in Montreux, Switzerland. Few attended. Nothing came of it. In short, fascism was a reality limited to Italy. But fascist Italy was first to enact the disempowerment of legislatures and the empowerment of the administrative state that is now the Western world’s standard of government.

Birth of a Slur

Communists in general and Joseph Stalin in particular are responsible for turning the words “fascism” and “fascist” into mere negative epithets. They did this as a result of a major tactical decision regarding the political wars of the 1920s and ’30s, which pitted the Communists against the rump of the socialist movement as well as against various nationalist and conservative movements. For the Communists, the practical, tactical question was whether to seek power alone or to ally against the conservatives and nationalists with the socialists or whomever. Early experiences had been equivocal. Hungary’s Béla Kun had taken power alone but had been overthrown quickly. In Italy the Fascists, led by a socialist, had swept the Communists from the streets while the socialist party stood by. In 1922-23, Germany was the big question. Its socialist party was really the only big nationwide force other than the Christians. The two did not get along. Stalin judged that the Communists could defeat them both, and the National Socialists, too, acting alone. Perhaps most of all he feared that if Communists were to ally with movements not under his control, he might lose control of the Communists.

Hence, Stalin elaborated the doctrine of “social fascism” which, verbiage aside, meant that Communists should consider all to the right of them—essentially all who were not under Communist discipline—as “fascists.” Stalin wrote:

Fascism is the bourgeoisie’s fighting organization that relies on the active support of Social-Democracy. Social-Democracy is objectively the moderate wing of fascism. There is no ground for assuming that the fighting organization of the bourgeoisie can achieve decisive successes in battles, or in governing the country, without the active support of Social-Democracy. There is just as little ground for thinking that Social-Democracy can achieve decisive successes in battles, or in governing the country, without the active support of the fighting organization of the bourgeoisie. These organizations do not negate, but supplement each other. They are not antipodes, they are twins. Fascism is an informal political bloc of these two chief organizations; a bloc, which arose in the circumstances of the post-war crisis of imperialism, and which is intended for combating the proletarian revolution. The bourgeoisie cannot retain power without such a bloc.

In 1935, after the Communists had lost Berlin’s streets to the Nazis and Hitler had taken power, Stalin dropped the notion that everything to the right of him was fascism and reversed tactics. Thereafter, “popular front” became the watchword—meaning Communists would ally with everyone, under whatever banner, to defeat his worst enemies. The Spanish Civil War was the biggest of Moscow’s early popular front campaigns. In the post-war world, Communist fronts consisting of a few “witting” and many “un-witting” participants were Soviet foreign policy’s hands and feet. The Soviets’ political defeat of the U.S. in Vietnam will remain a textbook of popular front warfare. In one way or another, “popular front” has remained the operational doctrine of orthodox Communists.

But the notion that everything to the right of Communism is fascism remains a fixture in the minds of Communists and other radicals. They never ceased to think of non-Communists and especially anti-Communists as fascists.

Marxist ideology lets them do that. According to Marx, consciousness is epiphenomenal to class reality. Hence, what people think subjectively does not affect what they are objectively. Truth that is class-objective and hence politically correct, is whatever the party judges useful to itself. That is why Communists believe they may apply the term “fascist,” or any other, to people who do not think themselves so. But this reasoning, so clearly expressed, is adequate only among Communist apparatchiks.

For that claim to have force outside of the Stalinist canaille, for it to migrate into modern Western society’s bloodstream, it had to be translated into pseudo-academic form. The book The Authoritarian Personality (1950), by the Communist Theodor Adorno and researchers working at the University of California, Berkeley, began doing that by popularizing a test that purports to correlate personality traits with fascism—that is, Adorno’s F-scale (F for fascist). The test consists of a questionnaire that measures agreement with what Adorno calls “conventionalism, authoritarian submission, authoritarian aggression, anti-intraception [the rejection of all inwardness], superstition and stereotypy, power and ‘toughness,’ destructiveness and cynicism, projectivity, and [excessive] sex.” These are the characteristics by which Adorno defined fascists. The more someone responded affirmatively to the statements by which Adorno defined these characteristics, the more of a fascist he was supposed to be. The whole exercise’s validity depended on Adorno’s wholly arbitrary definitions. Since the test also looked into the subjects’ socioeconomic background, it filled out the predetermined, circular equation of fascism with the ordinary people whom progressives despise. Some version of that test and of that equation became conventional wisdom among the professoriate, the media, and the ruling class here and abroad.

The test’s fraudulence is based on the presumption that its author—not the historical record—may rightly define a historical phenomenon. The moment you have assumed the power to say what fascism, or anything, is—the moment you have taken it upon yourself to redefine reality—you may then correlate the work of your hands to anything else. And it helps if you also define that something else. The scam’s circularity is obvious—unless you’re part of it.

This author first encountered the scam in 1963 as a student at Rutgers University’s Eagleton Institute. The text assigned us, Herbert McClosky’s “Conservatism and Personality” (American Political Science Review, 1958), consisted of one questionnaire to measure conservatism, as defined by McClosky, and a second designed to measure personality traits, most of which were translations of Adorno’s F-scale. The article touted its scientific bona fidesby stating that both sets of definitions had been submitted to, and certified by, experts, including McClosky’s graduate students. Not surprisingly, the project’s results showed a strong correlation between conservatism and repulsive, dangerous personality traits.

Having received permission to do a term paper on that article, I replicated it as “Liberalism and Personality,” using the same “scientific” methods—likeminded friends—to validate the questionnaires as McClosky had for his. What do you know? The results showed that liberals suffer from even worse disorders than conservatives, many unmentionable in a family publication. Only one of my professors cracked a smile.

Manufacturing Fascists

Not one in a thousand of today’s Western establishment politicians and publicists has heard of Adorno or McClosky. Generations removed from Communist professors, they know and care as little about Marx and Stalin as they do about Mussolini. But establishmentarians, confident that nobody wants to be governed by fascists, now justify their claim to power and privilege just as orthodox Stalinists do: “it’s us or the fascists!” Wanting to de-legitimize their conservative opponents, they call them fascists, then define what conservatives think and do as fascism. Or they run the scam in reverse: define fascism in terms of the things their least favorite people do, and then define those things as fascism. Conservatives are fascists. Get it?

A July 2019 article by Jay Willis in GQ magazine, for example, begins by acknowledging uncertainty about the fascist label’s applicability, and acknowledges that its widespread use has diluted or “muddied” its effect on the electorate. But the article resolves the problem with the scam’s patented circularity. It tells us that Professor Jeffrey Isaac of Indiana University and Thomas Dumm of Amherst College certified that fascism consists of reaction to “social upheaval,” “nostalgia for a lost, glorious past,” “the scapegoating of minority groups,” “a strongman savior,” “the stifling of dissent,” and “ritualistic community bonding”—the experts’ very own F-scale. Unsurprisingly, it turns out that according to these, Donald Trump is as quintessentially fascist as Hitler on all counts and equally worthy of exclusion from polite society. That crude conclusion also seemed to be Hillary Clinton’s point in a talk delivered at Wellesley last summer. Citing Madeline Albright’s 2018 book, Fascism: A Warning, she said of Trump: “The demagoguery, the appeal to the crowd, the very clever use of symbols, the intimidation, verbal and physical...is a classic pattern.” Demurely, she left it to the audience to use the f-word.

Albright herself, and other “high-end” establishmentarians, dance suggestively around the charge that Trump—and those who vote for him—are fascists. At least, they say, Trump and his supporters are undemocratic. They so threaten “democratic institutions” and are enough like fascists to make us legitimately worry that they might be fascist. They do not explain how officials elected by the people—some overwhelmingly, like Hungary’s Viktor Orbán—can be undemocratic. But the power to define anything any way you like, and to pin any label on anyone you dislike, absolves you from having to explain your words’ relationship to reality. All you have to explain is how urgent it is to exclude from polite society whoever disagrees with you.

In “The Failure to Define Fascism Today,” published on the New Republic’s website last June, Geoffrey Cain ritually bows before the fact that today’s circumstances are nothing like those of the 1920s and ’30s, and that the DNA of today’s political movements is peculiar to our circumstances. Nevertheless, he quickly falls back on the authoritative opinions of academics, who certify that today’s conservatives sure look like fascists, and fulfill what the experts say are fascism’s essential definition: “an alliance of hardline and moderate conservatives...a campaign to convert the working classes to nationalism, to make them angry and violent, to convince them that they’ve been betrayed by their global-elite leaders.” Note well that this definition is not history, but rather another made-to-order F-scale. These are easy enough to manufacture. Anyone can make one to order. So can you.

Cui Bono?

But what is the point of repeating from society’s commanding heights that the ruling class’s opponents are fascists, fascistizing, near-fascists, Nazis, white supremacists, racists, and so forth?

Today, those words mean simply that those so indicted have no right to challenge the ruling class. Whatever they do in that regard is illegitimate. Whatever may be done to quash them is legitimate, because it involves saving all things decent. The accusation’s primary audience is all who exercise any kind of power over others. The accusations authorize, indeed urge this audience to inflict summary punishment. The indictments’ volume and vehemence, the variety of places whence they come, reassures whoever would use them that they may be sure of support as they indulge their noble rage to hurt those so indicted.

The most authoritative opinions from the most authoritative sources now urge doing whatever possible to exclude conservatives, now defined as fascist, etc., from government and the professions, from the possibility of wealth and influence, indeed from polite society. Why should bureaucrats, corporate officials, police and prosecutors, judges, reporters, editors, and others hold back from following such authoritative judgments? And if conservatives resist being marginalized, or just protest, all manner of regulations can be invoked, and administrative devices can be used to limit, isolate, discredit them, and to shut them up. And if that does not suffice, the authorities can stand aside serenely as groups such as Antifa (the famous “anti-fascists”) and the Service Employees International Union’s organizers disrupt them forcibly and hurt them physically. Sponsoring or simply tolerating gangsters who attack your enemies is a time-dishonored practice from every nasty regime that ever was.

To engage in these practices in 1922-26 and in 1933-34, Mussolini and Hitler had to change Italy’s and Germany’s basic laws because, although they controlled the government, they did not yet control society’s commanding heights: the judges, schools, businesses, press, and religious establishment. But because the 21st century’s ruling class has almost a monopoly of all those heights, it does not really need new laws. Having seized the power to make words mean whatever they want, as well as the power to include and exclude from society’s prime places, they are the law.

Our ruling class increasingly labels people fascists—but not for doing or saying things other than what they did or said in previous decades. Those who are so labeled have not changed. Indeed, those who call them fascists chastise them for refusing to abandon their ways. Nor has fascism changed. It is one of history’s closed chapters—except for the theory and practice of political economy that it invented and that is now well-nigh universal. Hence, the invidious labeling and the punitive consequences result from a change in those who impose them. We may understand that change as the progressive deformation of liberalism.

That people who still sometimes call themselves “liberal,” who had once defined themselves in terms of all manner of freedom, should vilify and try to hurt those with whom they disagree is counterintuitive. But our liberal, or formerly liberal, ruling class’s claim exclusively to embody enlightenment and righteousness, its taste for humbling those outside itself, is our time’s predominant reality. That claim, that taste, are impervious to reason.

We may understand why they are impervious, and hence why fighting that class is the only alternative to submission, by reference to the German sociologist Robert Michels. At the turn of the 20th century, he developed what he called the “iron law of oligarchy,” which argued that any and all human organizations, regardless of their ostensible purpose or structure, end up serving the interests of their leaders. These interests, he said, are inherently selfish. Michels made his case in terms of modern social science. But his thesis is anything but modern. One need only mention Lord Acton’s dictum that power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely, as well as the Book of Genesis’s illustration of pride as the origin of sin. Not incidentally, Michels moved to Italy and joined Mussolini.