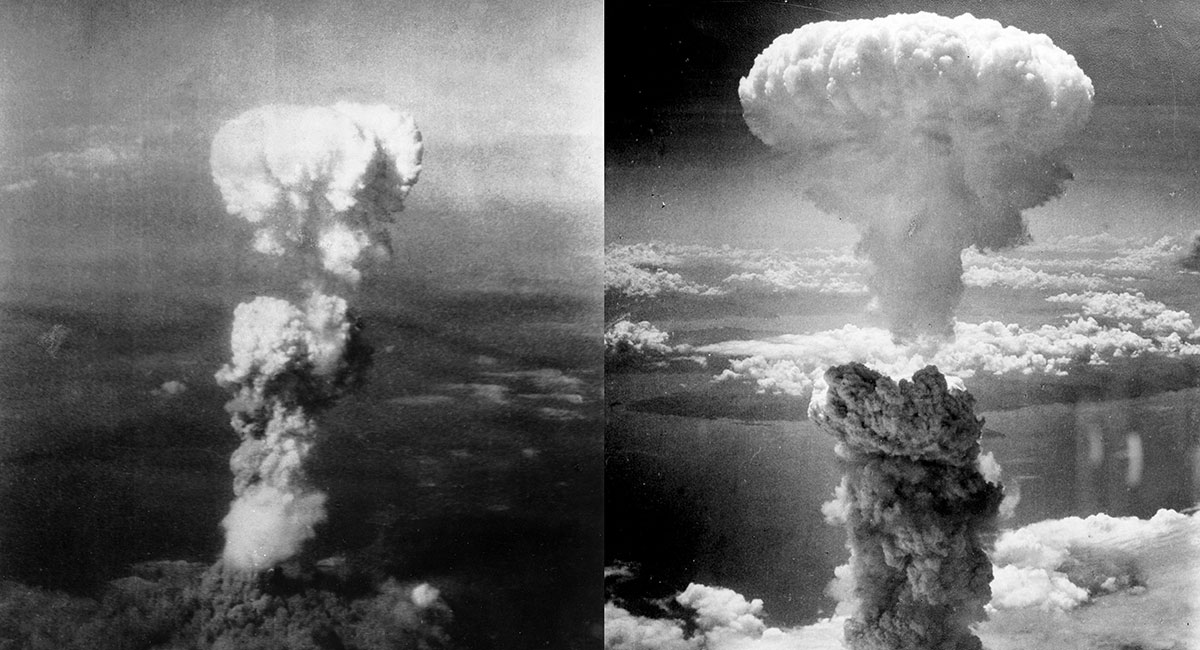

On the 75th anniversary of the dropping of the atomic bombs—“Little Boy” and “Fat Man”—on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, a debate still rages about whether the United States should have used the weapons. That’s because the 129,000 to 226,000 dead were overwhelmingly civilians.

International law clearly denotes the disproportionate killing of civilians as a war crime. Yet, the winners of war write history, so American school history books usually either blandly report the bombings or put them in the broader context of battling the evil Japanese Empire, along with its Nazi German and Italian fascist allies, in the most gargantuan clash of good and evil in human history—the great World War II.

And while it is true that by their aggression and their own war crimes, the Japanese, Germans, and Italians killed millions more noncombatants than the United States and its Western allies, some troubling questions linger about the allied use of the intentional bombing of cities. From even a morally superior position in a democracy on the winning side, we can (and should) critique our own government’s actions without being attacked as “unpatriotic.”

After all, defending debate and dissent in a free society, against the forces of genuine evil, is what we were fighting for in this war. And we should have had higher standards than those evil enemies, right?

Although the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were historically significant because they ushered in the nuclear age, which eventually brought forth the much more powerful thermonuclear H-bombs and a balance of nuclear terror, these first atomic weapons made the targeting of enemy cities more efficient. Instead of incinerating civilians with bombing runs of hundreds of planes—as was done in the firebombing of Dresden, Hamburg, Tokyo, and other Axis cities—the same mass destruction could be had with only two aircraft, one each over Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In both Germany and Japan, such mass killing of civilians were done in 1945 as both enemies were on their last legs. War crimes are more often committed when combatants are exhausted and frustrated with the length or intensity of a conflict or the tenacity of enemy resistance.

In the Pacific theater of World War II, the Japanese resistance was fierce, the dropping of the atomic bombs was justified on the basis that an invasion of Japan’s home islands would have cost an estimated one million allied casualties.

When I was in junior high school in the early 1970s, I came home from school and told my father we had debated whether the bombs should have been dropped. He quickly confounded me with the argument that I might not have been in the world if the bombs hadn’t been dropped, because he was slated to be part of the U.S. forces that would have invaded Japan if the Japanese hadn’t surrendered.

As I grew older, I realized that there were several problems with this argument. First, did the atomic bombings of August 6 and 9 in 1945 trigger the Japanese surrender on August 15? Some analysts believe that the triggering event was actually the Soviet Union’s entrance into the war on August 9. Second, although Japanese resistance had been fierce, were the huge casualty estimates for an invasion plausible? In fact, the estimates were extremely soft. More troubling was the willingness to kill civilians to reduce combatant casualties based on those hazy estimates.

Third, the allies at the Potsdam Conference on July 26th, before the bombs were dropped, demanded “unconditional surrender” from Japan or that nation would face “prompt and utter destruction.” To Japan, this meant giving up their sacred emperor, which they would not do; they ignored the ultimatum. In most wars, a settlement with conditions are negotiated between the winners and losers. Unconditional surrender usually makes the enemy–fearing subjugation and humiliation–fight harder. In this case, the United States did not make unconditional surrender stick, because the Japanese eventually got to keep their emperor, even after the atomic bombings. Finally, and most important, dropping the A-bombs were not the only alternative to an all-out invasion of Japan.

Japan is an island, and by August 1945, the U.S. Navy had overwhelmingly crushed its Japanese counterpart. The U.S. Navy could have imposed a tight blockade around Japan’s home islands, allowed a minimum of food, medicine, etc. in for humanitarian purposes, and simply waited for Japan to capitulate. This option would have saved hundreds of thousands of civilian lives and allowed the United States to have avoided stooping to the low regard for civilian life that its enemies exhibited on so many occasions.

However, a naval blockade of Japan would not have fulfilled perhaps the real purpose of the atomic bombs: demonstrating the power of the new weapon to a then ally and likely future enemy—the Soviet Union. President Harry Truman delayed testing of the atomic bomb until the Potsdam Conference with Winston Churchill and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, and comments were made at the conference that Truman wore the bomb ostentatiously on his hip to intimidate Stalin. However, it was morally questionable to drop powerful bombs on Japanese civilians, killing hundreds of thousands, merely to impress a possible future enemy with U.S. technology and power.

Ironically, Stalin already knew the power of the bomb because his spies had thoroughly penetrated the Manhattan Project. In short, a slightly porous U.S. naval blockade of Japan would have been far superior to the atomic mass killing of civilians, which has remained a stain on the otherwise defensible allied defeat of the Axis powers; the only use of atomic weapons heretofore in history is still used in propaganda by U.S. nuclear adversaries and wannabes, such as China, Russia, Iran, North Korea, and Iran.