After the Republican Party got a bloody nose over President Trump’s shutting down of the government in attempt to get his border wall, gun-shy congressional Republicans will probably put their foot down on any attempt by Trump make good on his continuing threats to do it again for the same reason.

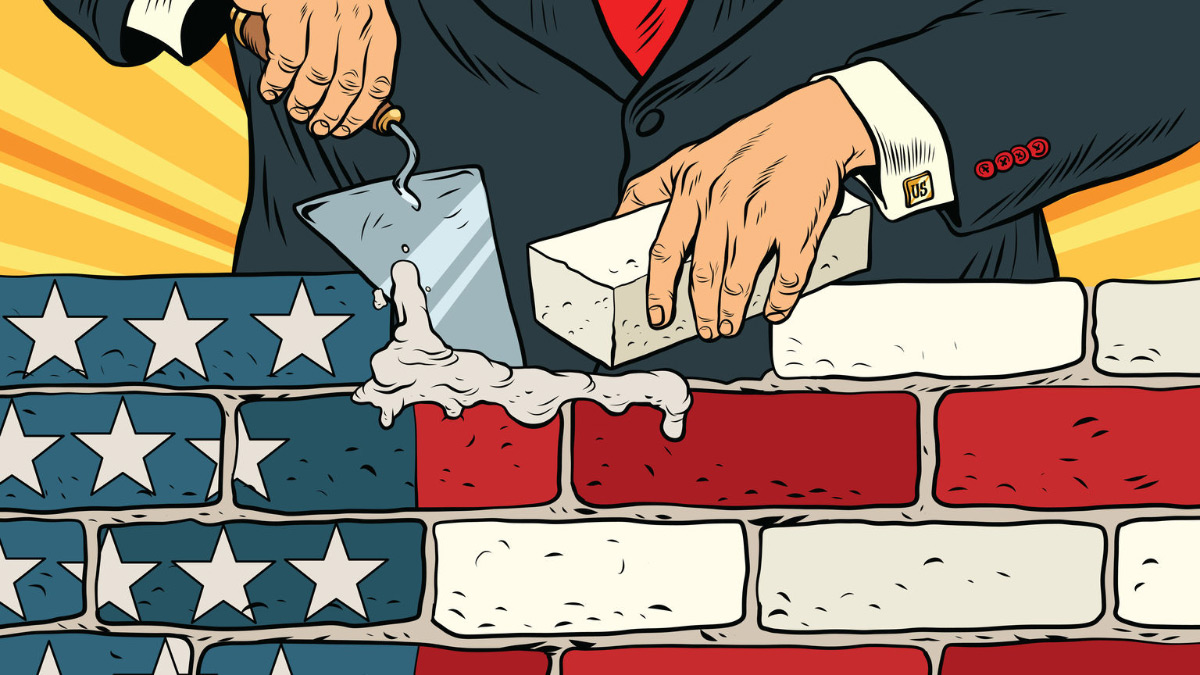

Thus, the impetuous president may see only one option to get money for his central campaign promise: declaring a state of emergency to raid money normally used for the country’s defenses to build the wall—even though he refrained from announcing it during the State of the Union address.

Aside from the fact that the generals at the Pentagon will not be happy with the president’s precedent for stealing their cash, any state of emergency, especially for a border wall that is likely to be ineffective in securing the nation’s southern border, is of questionable constitutionality.

Make no mistake, past presidents have declared states of emergency for various reasons, so much so that in a congressional pushback spurred by the Vietnam War and Watergate in the 1970s, Congress chose to “sunset” many of them.

Unfortunately, the number of emergencies has crept up again to more than 30 currently in effect. Yet just because past presidents have made such declarations, primarily to seize assets of countries around the world that have fallen out of U.S. favor, such precedents do not constitutionality make.

The nation’s founders, chary of British central monarchical power, made no mention in the Constitution of allowing the executive or Congress to declare states of emergency, even in the trying times of war, insurrection or disaster.

The Constitution’s 10th Amendment didn’t rule out states doing so, stating that any power not specifically delegated to the central government, nor prohibited to the states, would be reserved for the states or people.

The most dire remedy the national government is allowed is only the limited suspension of habeas corpus (the right of people to challenge their detention by the government) during an enemy invasion or domestic insurrection.

Even then, the document implies that denial of this basic right will be only temporary until the security situation is remedied and must be undertaken by the peoples houses of Congress, not the executive.

Therefore, President Trump has little credible constitutional ground to stand on—only the questionable precedents of prior presidents done for much different reasons—if he indeed pulls the trigger on declaring a state of emergency to get his trivial, expensive border wall.

Such an action, however, might be another important wakeup call to Congress and the American people that since World War II, they have willingly and dangerously continued to abdicate their constitutionally given power to a presidency that became first “imperial” and then “rogue.”

Wars always augment presidential power vis-à-vis the other branches of government because democratic bodies have a “collective action” problem when running military operations, i.e., too many cooks in the military and economic kitchen.

After World War II, President Harry Truman saw the already strong presidency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt beefed up institutionally by the National Security Act of 1947, which gave the president unified command of all armed forces under a new Department of Defense, a new National Security Council in the White House to run U.S. foreign policy and a new intelligence arm (the CIA) that did not report to the military commanders and could undertake secret presidential wars, unbeknownst to Congress and the public.

Such institutional augmentation was supplemented by Harry Truman’s use of mythical “inherent” executive power not in the Constitution and his abuse of the commander-in-chief power at home and abroad, which was intended by the founders to be limited to commanding troops on the battlefield. Thus, the “imperial presidency” was born.

That version of a too-powerful presidency was then further augmented to “rogue presidency” after the attacks on 9/11 (although hints of it became apparent as early as 1999 during the Bill Clinton’s war over Kosovo, when he flagrantly disregarded the congressionally passed War Powers Resolution).

After 9/11, under President George W. Bush, the U.S. used torture, illegal domestic surveillance, suspended habeas corpus for terrorism suspects and used unconstitutional kangaroo military tribunals for the same. Although President Barack Obama ended torture, he continued the other rogue, unconstitutional practices.

Thus, America is now left with a presidency on steroids—something the Founding Fathers never intended, as is evidenced by the Constitution’s allocation of most powers to the states and Congress—and a current president with enough autocratic tendencies and rhetoric to potentially abuse the powers of the office even more.

Any Trump declaration of emergency over the border wall would be a major red flag that he intends to do so. Will Congress, wracked by severe partisanship that has further eroded the founders’ system of checks and balances, quit abdicating its constitutional power and push back to save the republic?