The Early Years

Born in Paris in 1805, AlexisCharles-Henri Clérel de Tocqueville entered the world in the early and most powerful days of Napoleon’s empire. His parents were of the nobility and had taken the historical family name of Tocqueville, which dated from the early 17th century and was a region of France known previously as the Leverrier fief.

Tocqueville’s father supported the French monarchy and played no serious role in public affairs until after Napoleon’s final defeat at Waterloo, which followed the restoration of the monarchy under the Bourbon king Louis XVIII in 1814. The elder Tocqueville then served as prefect successively at Metz, Amiens and Versailles. Alexis followed his father in civil employment when, at the age of 21, he was appointed magistrate at Versailles. Alexis had studied rhetoric and philosophy in secondary school and at the College Royale before studying law for three years in Paris.

It was at Versailles that Alexis met Gustave de Beaumont, a deputy public prosecutor, who became both his lifelong friend and his traveling companion to America. Ostensibly, their trip through America was a leave for the two men to study the prison system in the eastern United States. But according to Beaumont, behind that pretext lay an interest in and a desire to study American democracy more generally.

And so, Tocqueville and Beaumont landed in New York on May 10, 1831, and began what became one of history’s most famous journeys. The result was two books, both of which would bring Tocqueville fame and honors. In 1833, about a year after Tocqueville returned to France, the report on American prisons, The U.S. Penitentiary System and Its Application in France, was published.

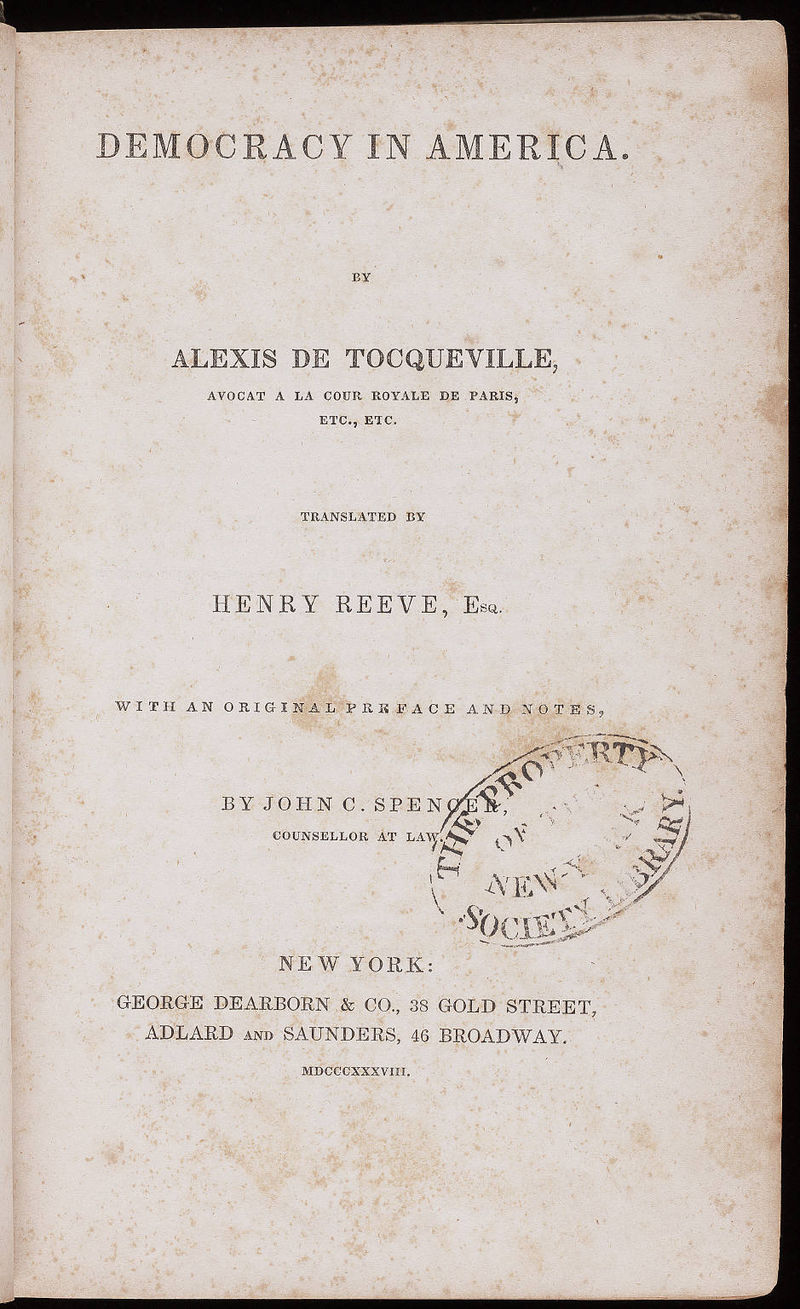

Things in France changed for Beaumont and Tocqueville upon their return after 10 months in America. Both men left the judiciary. Beaumont was officially let go, and Tocqueville resigned in sympathetic protest. Tocqueville then had ample time to work on his masterpiece, Democracy in America. Volume 1 was published in 1835. The English translation appeared later that same year to wide European and American acclaim. The more philosophical Volume 2 was published in 1840.

From its first appearance, this work has been considered a masterpiece of observation, speculation, historical writing and sound political theorizing. Its author was elevated to the League of Honor, the Academy of Moral and Political Sciences and finally, in 1841, to the French Academy. Democracy in America was translated into all major languages at the time and sold all over the world.

The Political Years

Tocqueville ran for the Chamber of Deputies, losing in 1837 but winning in 1839 and then serving continuously until 1848, voting as an independent constitutionalist. He married Mary Mottley in 1835 and, upon his mother’s death the following year, inherited the family estates in Tocqueville. After the revolution of 1848, which Tocqueville alone predicted a month before it occurred, he was elected to the Constituent Assembly in Paris. With Louis Philippe’s abdication, the so-called Second Republic died in 1848.

Although Tocqueville had little love for the departed monarchy, he feared the Parisian revolutionaries because he considered all revolutions a threat to general liberty as they unfolded. (His view, no doubt, was influenced by his own family’s tribulations during the French Revolution. His father and mother escaped the guillotine by the narrowest of margins.) He sat on the committee that drafted the new French constitution, but his opinions in support of both separation of powers and bicameralism were rejected by the whole assembly. Tocqueville’s effectiveness in the legislature was greatly hampered by his inability to compromise.

Having completed the new constitution by the end of 1848, France then elected its first independent president, Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, nephew of Napoleon I. Tocqueville distrusted Louis Napoleon, and his misgivings were shortly borne out.

Tocqueville became a member of the new National Assembly in 1849 and the new government’s emissary to Germany. He was named foreign minister as Louis Napoleon sought, without subtlety, to secure Tocqueville’s support. But when Louis dissolved the National Assembly in 1851 because under the constitution he could not be re-elected, Tocqueville withdrew his guarded support. Louis staged a military coup. For his vocal opposition to this act of political usurpation, Tocqueville was imprisoned overnight. He wrote an account of his ordeal and a strong criticism of Louis Napoleon’s tactics that was smuggled out of France and published in Britain’s London Times. In general, Tocqueville was more effective as an observer–writer than as a politician.

The Final Years

In the spring of 1849, Tocqueville became ill and was diagnosed with tuberculosis. By 1852, he was forced to withdraw from public affairs because he refused to take a loyalty oath to the new regime and also because he was in failing health. He went into “internal exile.”[1] But he continued to write until his death at 54 in 1859. His book Souvenirs (1851) was a mirror through which he observed himself.[2]

Another celebrated work, The Ancient Regime and the Origins of the French Revolution (1856), demonstrated that the strongly implied egalitarian leanings of Democracy in America had become tempered by an equally intense distrust of popular revolutionary periods.

Tocqueville traveled widely and saw a great deal of political intrigue during his productive middle years, and he left us a rich legacy of early sociological insights.[3] He was an accurate observer, even though he was passionately intense toward all his subjects. Yet, despite his zeal, as a historian and chronicler he managed to remain virtually dispassionate.[4] In this approach, Tocqueville set a standard that modern social scientists and historians would do well to emulate. He remains one of the most reliable sources on the early history of the United States, for unlike so many of his literary contemporaries, he harbored no animus toward the country and was an honest observer.

Over the years, some commentators have raised questions about Tocqueville’s visit to America, mostly centered on its timing and execution. For example, the entire trip lasted 286 days, a short period given the scope of his planned travel and the state of public and private transportation. Of those days, 271 of which were in the United States, 140 were spent in cities—mostly in the North and West—and only 40 were spent in the South. Is Tocqueville’s analysis biased by Northern urbanity? Biographer Andre Jardin best sums up this unfortunate, if accidental, allocation of travel time: “It was during these years [specifically, 1836] that Michael Chevalier made the distinction, which has remained classic, between two types of Americans, the Yankee and the Virginian. Tocqueville observed and listened to the first much more than to the second. This was not deliberate—the latter part of their stay was disrupted...and unforeseen incidents forced them to change their plans so that they were not able to remain in Charleston, where they had intended to study Southern society, or to visit James Madison, the former president, now in retirement at Montpelier, his home near Charlottesville, Virginia.”[5]

To what extent Tocqueville might have produced a different work had he spent more time in the American South, with its major cultural differences when compared with the industrial North, must remain speculative. But given his time and travel limitations, Tocqueville produced a magnificent account of the “essence of America” as he saw and felt it.

Democracy in America is a classic of both historiography and sociology. Tocqueville is much more a 19th century interpreter of America—and its various possible futures—than a detailoriented diarist on a long field trip. His work elucidates why he admired America but doesn’t omit those aspects he didn’t admire. He lists in detail some of his fears for the new nation’s possible future. Americans can still profit immensely from his discourses on the problematic nature of pure, majoritydriven power, a fear shared by the founders who wrote the U.S. Constitution. Like Lafayette before him, Tocqueville left America the better for having been here. His body rests today on his old estate in the village of Tocqueville, near modern-day Normandy.

Notes

[1] Jardin, Andre (1988), Tocqueville: A Biography (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press), Part V.

[2] Jardin, Andre (1988), Tocqueville: A Biography (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press), 453.

[3] Barzun, Jacques (2000), From Dawn to Decadence (New York: Harper Collins), 538.

[4] Barzun, Jacques (2000), From Dawn to Decadence (New York: Harper Collins), 537.

[5] Jardin, Andre (1988), Tocqueville: A Biography (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press), 107.