No one knows whether the famous expression about Washington’s endorsement of Third World dictators—“He’s a son of a bitch, but he’s our son of a bitch”—was said by Franklin Roosevelt or Cordell Hull or was invented by a chronicler. But it also seems to describe the tolerance the United States and Europe have shown in the last couple of years toward the brutal Saudi Arabian royal family.

We should not be surprised that, as is almost certainly the case, Riyadh felt confident enough to send agents to Istanbul to kill and dismember Jamal Khashoggi, a dissident Saudi journalist.

It is widely accepted as a matter of realpolitik that the foreign policy of liberal democracies cannot always be based on the principles that inform their own constitutions. But even accepting, for argument’s sake, this cynical idea, there are lines we should never let dictators cross if we want to prevent foreign policy from making a mockery of everything liberal democracies claim to represent.

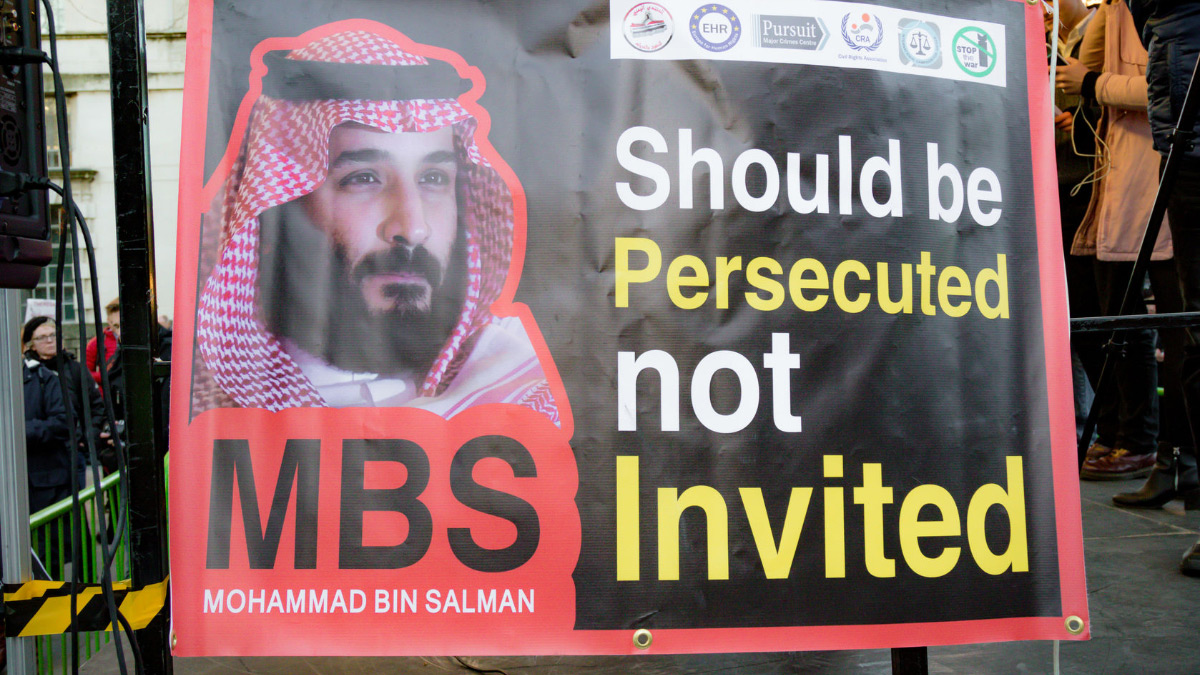

Not understanding this notion has been the great mistake of Mohammed bin Salman, the Saudi crown prince, who, under the mantle of economic modernization and episodic concessions to secularism, is terrorizing his country and has now embarrassed, even humiliated, his international protectors.

The United States and Europe use Saudi Arabia against Iran, a major foe of Riyadh; appreciate bin Salman’s efforts to displace the Islamic State among the Sunnis by confronting the Shiites and their allies; and believe they need the Saudis to help stabilize oil prices.

But the assassination commando that, according to substantial reports, killed and dismembered the Washington Post’s contributor (not exactly a Jeffersonian democrat: he had been close to part of the Saudi regime and then sympathized with the Muslim Brotherhood) reverses the hierarchy between the western powers and their indelicate vassals. The message from Riyadh is that it has the United States and Europe at its mercy and that these will not dare take punitive measures.

It is one thing for a dictatorship to keep up appearances so as not to raise the cost that liberal democracies pay for tolerating or supporting them, and quite another for it to act brazenly as if the values of civilization that those liberal democracies represent have become completely irrelevant to the world order.

When Donald Trump, pushed by some Republicans, originally suggested that if it was proven that Riyadh was behind the crime, there could be consequences, the Saudis threatened to provoke a cataclysm in the oil market (Trump backtracked soon after). That was the insolent response of the same regime that felt strong enough to ignore the U.N. report holding Riyadh accountable for most of the 16,000 civilians killed in the Yemeni war and turned a tweet from the Canadian government protesting the arrest of a women’s rights activist into a pretext for expelling that country’s diplomats and ordering Saudi scholarship recipients in Canada to return to Riyadh. It was also the self-confident statement of a government that has boasted it could stop buying U.S. arms ($90 billion in the last decade) and start buying arms from Russia or China.

Saudi Arabia is wrong: It needs the United States and Europe, not the other way around. The House of Saud’s confrontation with Iran, its archenemy in the Islamic world, is almost existential (as is its rivalry with the Islamic State). Its ability to control oil prices—now that OPEC only accounts for one-third of world production and that the United States is on course to extract 14 million barrels a day—is smaller than before.

Bin Salman’s policy of economic diversification aimed at ending Saudi reliance on black gold cannot be successful without European and American capital. And the cost of transforming Saudi Arabia’s military apparatus to adapt it to the (inferior) Russian technology would be huge and time-consuming.

It is time for the United States and Europe to turn their backs on bin Salman before the door of the kennel becomes wide open and the canines get out of control.