Is there a greater tragedy imaginable than that, in our endeavour consciously to shape our future in accordance with high ideals, we should in fact unwittingly produce the very opposite of what we have been striving for?

—F. A. Hayek

Most of us “know” that eating too much saturated fat (which includes red meat, dairy products, and eggs) raises our cholesterol levels and puts us at risk for heart disease. While we’re at it, we should greatly cut down on the salt too. These lessons are reinforced in our health classes and what the media has been telling us for decades. After all, this is the consensus reflected in the “Dietary Guidelines for Americans” issued by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and backed up by allegedly solid, objective science from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). As extra reassurance, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) will use its regulatory authority to crack down on trans fats, the worst villain of them all.

Most of us “know” that eating too much saturated fat (which includes red meat, dairy products, and eggs) raises our cholesterol levels and puts us at risk for heart disease. While we’re at it, we should greatly cut down on the salt too. These lessons are reinforced in our health classes and what the media has been telling us for decades. After all, this is the consensus reflected in the “Dietary Guidelines for Americans” issued by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and backed up by allegedly solid, objective science from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). As extra reassurance, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) will use its regulatory authority to crack down on trans fats, the worst villain of them all.

Despite the appearance of a seemingly united front in the war on obesity, sharp dissent over sound nutrition policy is silently bubbling beneath the surface. It may be a sign of the times that fundamental challenges have come to the forefront and are becoming increasingly accepted. Growing numbers of scientists are expressing public skepticism toward the federal government’s official low-salt guidelines. Back in February of this year, the government’s top nutrition panel withdrew its nearly forty-year-old warning on restricting cholesterol intake and grudgingly concluded that “available evidence shows no appreciable relationship between consumption of dietary cholesterol and [blood] cholesterol.”

The Health Consensus UnravelsIn one of the Wall Street Journal’s top-shared op-eds of 2014, investigative journalist Nina Teicholz threw down the gauntlet on the mainstream diet guidelines on fat:

“Saturated fat does not cause heart disease” — or so concluded a big study published in March in the journal Annals of Internal Medicine. How could this be? The very cornerstone of dietary advice for generations has been that the saturated fats in butter, cheese and red meat should be avoided because they clog our arteries. For many diet-conscious Americans, it is simply second nature to opt for chicken over sirloin, canola oil over butter.

The new study’s conclusion shouldn’t surprise anyone familiar with modern nutritional science, however. The fact is, there has never been solid evidence for the idea that these fats cause disease. We only believe this to be the case because nutrition policy has been derailed over the past half-century by a mixture of personal ambition, bad science, politics and bias.

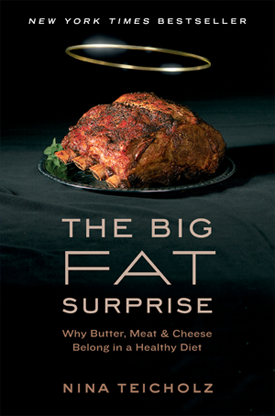

Teicholz elaborates upon her thesis in her eye-opening, best-selling book The Big Fat Surprise: Why Butter, Meat and Cheese Belong in a Healthy Diet. With over 100 pages of footnotes and an extensive bibliography, it is clear that Teicholz has done her homework. In her nine-year investigation, she extensively reviewed the scientific literature and interviewed many of the key personalities in government, private industry, and advocacy groups who played influential roles in crafting official nutrition policy. While many people might be tempted to blame “the nefarious interests of Big Food,” Teicholz came to discover that the “source of the our misguided diet advice ... seems to have been driven by experts at some of our most trusted institutions working towards what they believed to be the public good.”

The Rise of the Government ExpertCivic-minded Americans are generally familiar with Dwight D. Eisenhower’s famous warning in his farewell address to “guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence ... by the military-industrial complex.” Yet, there is another passage that deserves equal if not greater attention. Against the backdrop of the Cold War, numerous intellectuals were conscripted to become part of Leviathan, silencing their proper roles as critics of power:

Today, the solitary inventor, tinkering in his shop, has been overshadowed by task forces of scientists in laboratories and testing fields. In the same fashion, the free university, historically the fountainhead of free ideas and scientific discovery, has experienced a revolution in the conduct of research. Partly because of the huge costs involved, a government contract becomes virtually a substitute for intellectual curiosity. ... The prospect of domination of the nation’s scholars by Federal employment, project allocations, and the power of money is ever present — and is gravely to be regarded.

Yet, in holding scientific research and discovery in respect, as we should, we must also be alert to the equal and opposite danger that public policy could itself become the captive of a scientific-technological elite.

There is no better example of “public policy ... becom[ing] the captive of a scientific-technological elite” than with what happened with nutrition research and health policy. Ironically, the story of how saturated fat became demonized began in the Eisenhower years. After President Eisenhower suffered a heart attack, Washington policymakers became alarmed by the disease that was suddenly striking the ruling elite. After going into “Do Something!” crisis mode, it wasn’t long before they came under the sway of experts who offered easy answers. One such individual was Dr. Ancel B. Keys, the originator of the hypothesis that saturated fat causes heart disease. Keys went on to exercise perhaps the greatest influence in the “history of nutrition” through professional and personal dominance.

Opponents of the saturated fat–heart disease hypothesis included accomplished scientists George V. Mann and E.H. “Pete” Ahrens, who voiced many legitimate criticisms. But in the end, they were no match for the unprecedented changes rammed through by Keys and his sidekick Jeremiah Stamler. Through their efforts, these two men and their supporters blurred the line between objective scholarship and political advocacy. It wasn’t long before most skeptical nutrition researchers were browbeaten into submission, relegated to sidelines, or otherwise drowned out as the zeitgeist ultimately shifted in favor of Keys’s hypothesis and preferred solutions.

Dogma is a term that is usually associated with fundamentalist religions. But unfortunately, even scientists who are supposedly trained to think critically and independently are not immune to groupthink, the temptations offered by political prestige, and the limits of what’s “acceptable” as dictated by funding. Despite the shortcomings of various studies that appeared to provide a solid scientific backing, the saturated fat–heart disease hypothesis became a dogma when it was formally institutionalized within the US government’s public health bureaucracies. This was thanks to Keys’s relentless advocacy and intimate relations he established with the American Heart Association (AHA). The influence of the AHA over nutrition policy cannot be overstated. In fact, the “AHA and NIH were parallel, entwined forces from the start.” As the two main organizations responsible for setting the agenda and distributing millions in funds for cardiovascular research, it was increasingly difficult to “reverse course and entertain other ideas” even as the saturated fat diet–heart disease hypothesis continued to disappoint because it “had become a matter of institutional credibility.”

Congress and “Big Food”

To make matters worse, Congress became directly involved during the 1970s in the question of what the American people ought to eat. Teicholz explained how the Beltway culture allowed for bad ideas to take hold and stay entrenched (as anyone who has worked there can attest to):

With its massive bureaucracies and obedient chains of command, Washington is the very opposite of the kind of place where skepticism — so essential to good science — can survive. When Congress adopted the diet-heart hypothesis, the idea gained ascendancy as an all-ruling, unassailable dogma, and from this point on, there has been virtually no turning back.

Big Food manufacturers and lobbyists descended onto Washington and set up the Nutrition Foundation to funnel millions into research and thus were “able to influence scientific opinion as it was being formed.” Not surprisingly, “the promotion of carbohydrate-based foods such as cereals, breads, crackers, and chips, was exactly the kind of dietary advice large food companies favored.” These foods ended up receiving glowing endorsements from the official government nutrition elite. Despite what some might expect, meat and dairy interests’ lobbying efforts paled in comparison. Carbs and polyunsaturated fats (vegetable oils) were overwhelmingly favored over saturated fats. Consumption of red meat became increasingly demonized as new studies highlighted supposedly detrimental health consequences. Left-wing environmental movements also picked up steam during this time. In the name of “sustainability,” these campaigns and their advocates urged the reduction if not the complete elimination of meat from one’s diet.

The Data Doesn’t Say What Congress Thinks it SaysThroughout the book, Teicholz reviews the scientific literature by critically examining the hard data, not abstracts or executive summaries (the only sections most policymakers and researchers alike will ever read), and repeatedly points out various methodological flaws and limitations. In particular, she takes care to emphasize that epidemiological studies can show only an association between two elements, but “could not establish any casual connection.” Only clinical trials in carefully controlled settings could establish cause. Shockingly, almost all the early studies that were cited to support Keys’s hypothesis were epidemiological. The famous Seven Countries Study directed by Keys himself was an epidemiological study that appeared to show a strong correlation between consumption of saturated fat and heart disease deaths across international populations. Teicholz pointed out many confounding variables such as the fact that Keys examined the Mediterranean region in the aftermath of World War II. During this period, people were impoverished and ate abnormal diets. In addition, Teicholz revealed that Keys conducted some of his surveys during Lent (no meat for the faithful!) along with some other egregious examples of cherry-picking to fit his preferred narrative. Other prominent studies all suffered from similar defects. The Framingham Heart Study originally announced that high total cholesterol was a reliable predictor for heart disease, but a follow-up study thirty years later called those results into question. The Israeli Civil Service Study mentioned worshiping God lowered the risk of a having heart attack! Even with their weaknesses, these studies were repeatedly cited and the idea that saturated fat leads to heart disease continued to build into conventional wisdom.

Having studied anthropology, I was delighted that Teicholz highlighted glaring “paradoxes” by digging out several examples of indigenous populations that ate almost all meat and animal fat such as the Inuit and the Masai yet had virtually no recorded cases of heart disease, obesity, or any of the chronic diseases of Western civilization (that is until they added sugar and refined carbs to their diet). In her analyses of the clinical trials meant to establish cause and effect, she noted a disturbing caveat that came up repeatedly but was often buried: namely, following low-saturated fat diets did not extend overall lifespan. Speaking of clinical trials, it is worth mentioning the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), which enrolled 49,000 women in 1993 and aimed to validate the benefits of a low-fat diet once and for all. Here are the final disappointing results as summarized by Teicholz:

[A]fter a decade of eating more fruits, vegetables, and whole grains while cutting back on meat and fat, these women not only failed to lose weight, but they also did not see any significant reduction in their risk for either heart disease or cancer of any major kind. WHI was the largest and longest trial ever of the low-fat diet, and the results indicated that the diet had quite simply failed.

As Teicholz moved toward the present day state of affairs, she cites the work of award-winning science journalist Gary Taubes and a few brave, unorthodox researchers including Stephen D. Finney and Jeff S. Volek, who challenged the taboo against red meat and fat. Thanks to high-profile pieces in Science and the New York Times as well as a comprehensive book, Good Calories, Bad Calories, Taubes was more responsible than anyone in reopening the debate that carbohydrates, not fat, are the drivers of obesity and other chronic diseases. Even as more people today become aware of the deleterious effects from consuming high amounts of refined carbs and sugars, the permanent damage has been done thanks to the long-standing bias toward the saturated fat–heart disease hypothesis. Official policymakers embraced this view, advocacy groups added fuel to the fire, and restaurants and cafeterias altered their menus. Millions of Americans changed their eating patterns and avoided meat, cheese, milk, cream, and butter. In the end, the results are not pretty:

Measured just by death and disease, and not including the millions of lives derailed by excess weight and obesity, it’s very possible that the course of nutrition advice over the past sixty years has taken an unparalleled toll on human history. It now appears that since 1961, the entire American population has, indeed, been subjected to a mass experiment, and the results have clearly been a failure. Every reliable indicator of good health is worsened by a low-fat diet. ... Despite more than two billion dollars in public money spent trying to prove that lowering saturated fat will prevent heart attacks, the diet-heart hypothesis has not held up.

By the end of the book, it seemed very clear that almost everything Uncle Sam told us about the “dangers” of saturated fat is completely wrong. That being said, it is past time to demolish the USDA food guide pyramid. Let Teicholz’s exposé serve as a warning when political crusaders and their bureaucratic allies are allowed to force top-down solutions on everyone without ever having to face accountability for their mistakes no matter how egregious.

Concluding Thoughts

The Big Fat Surprise is a book I highly recommend for anyone interested in food history, the politics of nutrition research and health policy, and how institutions fail. For me, as an individual with a background in biological science who also happens to know the basic tenets of public choice theory, I was very pleased how Teicholz synthesized the science with a critical analysis on how rent-seeking special interests and bureaucracies actually behave. Even more impressive was how she managed to create a flowing narrative that read like a political thriller. The magisterial effort that went into this book makes it a worthy contender for a Pulitzer Prize.

In her conclusion, Teicholz reminds people of what is at stake (no pun intended):

Meat is the central food throughout all human history, as recorded by humans themselves. We’ve forgotten our history at our peril.

Given the large amount of positive press this book has already received, The Big Fat Surprise may very well be a game-changer in the national debate on what constitutes healthy eating. With the unfounded fears about meat and fat thoroughly eviscerated, the thriving “foodie” community, food freedom advocates, and proud and unrepentant carnivores like myself have every reason to push back against the busybodies, do-gooders, and prohibitionists of all stripes who wish to deprive us of these tasty, nutritious foods that we desperately need back in our lives.