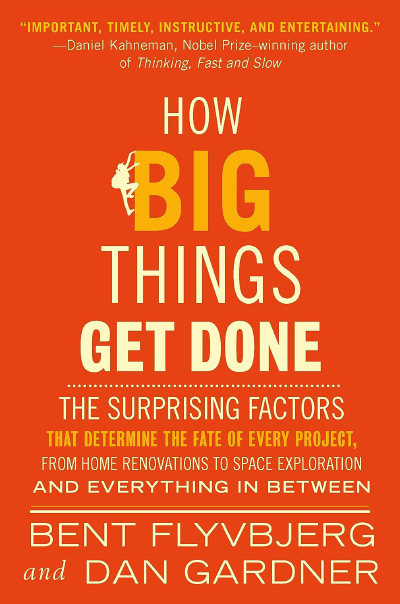

When an editor of The Independent Review asked me to review this book, I wondered if I would find the book of interest, if I would find the book relevant, and what qualifications I had to review it. Although the latter concern remains, Flyvbjerg and Gardner’s work on how big (and small) things get done is an interesting read that nearly anyone can relate to. Before reading, I had thoroughly researched South Carolina’s disastrous attempt to expand nuclear power in the state—a failed project that cost $9 billion and ten years before being canceled—and so found Flyvbjerg and Gardner’s accounts of other big projects’ cost overruns, construction delays, and unrealized benefits familiar. Nonetheless, How Big Things Get Done has something to say to anyone who has struggled to complete any project, from major construction to writing a dissertation to renovating the kitchen.

The numbers on big projects are bad indeed. The “Iron Law of Megaprojects,” over-budget, over-time, and under-benefit, is the rule, not the exception, and this law is supported by hard data and not simply casual observations or anecdotes. Flyvbjerg’s database of more than 16,000 big projects shows that only 8.5 percent are on-budget and on-time and that only 0.5 percent are on-budget, on-time, and deliver the promised benefits—and these numbers make no allowance for budget padding. The book is littered with examples of projects gone bad, from California’s High- Speed Rail to Japan’s Monju nuclear power plant, but Flyvbjerg and Gardner document success stories too, from construction of the Empire State Building to Pixar’s remarkable films.

Why are some projects a success and others a failure, often a colossal one? To provide a framework for answering this question, Flyvbjerg and Gardner divide projects into two phases, planning and delivery. They argue that projects usually don’t go bad during delivery; they start bad because of poor planning. But even if the planning is good, delivery needs to stay on schedule to close the window during which unexpected problems can arise to derail even the best-made plans. (Think the recent pandemic.) The rule for project success may be stated succinctly: “think slow, act fast.”

As useful as the planning-delivery framework is, it does not explain why people often think fast and act slow. Part of the explanation delves into the human psyche. We seem to be creatures beset by a number of psychological predispositions that make success in big projects problematic. But there is more. Big projects are about power, too, and humans like power.

If poor planning is the root of project failure, and psychology is the root of much poor planning, what psychological tendencies cause so many project leaders to plan so poorly? Much of the problem is the “commitment fallacy,” an intense desire to “do something” that overlooks goals, risks, and alternatives. Add in the human tendency for optimism and you have a recipe for disaster. But politics matter, too, when those who have a vested interest in a project budget based on figures that are politically acceptable rather than realistic, knowing that if they present a realistic budget, their projects will never be approved. “Strategic misrepresentation” leads to cost overruns and delays, but big projects mean big money and big power, and the desire to win the contract or get the project approved can trump honest assessment.

Utilizing the enormous project database and depth of experience, the authors lay-out broad principles that, if followed, greatly increase the likelihood of project success. One is to always keep sight of the goal, or, stated differently, to never stop asking why you are doing the project. Amazon’s Jeff Bezos and Apple’s Steve Jobs mastered this principle well.

Another principle is to utilize experience. Although this principle may seem self-evident, too many planners overlook or marginalize experience by yielding to other motives. Contracts are awarded based on political advantage or to favor local companies and create jobs. Egos drive decisions to be the first or the biggest. Flyvbjerg and Gardner point out that the Olympic Games systematically undervalue experience leading to huge cost overruns, with the 1976 Montreal Games the worst. In addition, a tendency of planners to consider their project unique undermines the perceived value of experience. Instead of considering their project unique, project managers should use reference class forecasting that relies on real world experience to provide helpful data, even if the projects in the reference class are not exactly alike. It is better to identify risks and mitigate them than to deal with a black swan.

The authors anticipate objections from those who believe that creativity is born of necessity and serendipity and so embrace a “just do it” approach in lieu of slow, careful planning. Such is the lore of Jimmy Hendrix’s Electric Lady recording studio and the blockbuster film Jaws. As appealing as these minimal-planning narratives may be, the data say otherwise: the odds that a benefit-overrun exceeds a cost-overrun is a mere 20 percent.

Getting the planning right is essential but so is getting the delivery right. And for that you need a team, whether hired or assembled. If the interests of team members align, cooperation, high morale, and a unified purpose are the result. Managerial credibility is important as is a culture that allows all parties to speak freely and obligates other parties to listen. The authors’ account of the construction of Terminal 5 at Heathrow Airport provides an inspiring example.

Delivery is enhanced by modularity. Modular assembly in lieu of on-site construction leads to repetition, learning, and the benefits of experience. Moreover, scale doesn’t matter because scaling up works. Examples are many, from subways to freight shipping. Flyvbjerg and Gardner provide evidence from their database that modular projects are fast, cheap, and less risky. Solar and wind farms are highly modular, low-risk projects. At the other extreme, nuclear power plants and the Olympic Games are the least modular and have the highest risk. The authors hold out hope that modular solar and wind farms will play an increasing and important role in reducing climate change.

The knowledge and experience of the author—Flyvbjerg is an Oxford professor and consultant in megaprojects of world renown—leave little room for criticism. This said, I would have liked to see the roles of government regulation in higher cost and longer completion times addressed in detail. The construction of the Empire State Building, the authors’ beginning success story, began in 1929 and was completed in 1931. In today’s world, could the Empire State Building be built, from planning to opening, in just over two years? I think everyone knows the answer. In pointing out the success of modularity, the authors point out that even in China, an undemocratic country where regulations can be swept away by authoritarian fiat, solar and wind farms are more successful than nuclear power plants. Yes, modularity works. But a far better comparison to test the effects of government regulation would be the construction of nuclear power plants in the democratic West versus the construction of nuclear power plants in authoritarian China. More generally, a comparison of big projects in centrally planned communist regimes with big projects in market capitalist countries would be of interest.

Big projects are part of human civilization, from ancient pyramids to modern undersea tunnels. Of course, most people do not plan at that scale. Nevertheless, businesses and nonprofits, small and large, and governments plan everything from what inventory to carry and what products to research and develop to the size and equipment of the fitness room of the local YMCA to military tactics. And in our individual lives, even the smallest plans matter. Have not many of us felt the frustration of preparing dinner only to realize we did not have a key ingredient?

The opening days of an Economics 101 class stress the reality of scarcity and the need to allocate resources efficiently as a result. Flyvbjerg and Gardner provide guiding principles, and the data to support them, to help ensure that costs in time and money are minimized and that beneficial outcomes result. Because scarcity matters, their work and guiding principles apply to businesses, nonprofits, governments, and our individual lives. Their work is well worth reading because of its relevance, broad appeal, and countless applications.

| Other Independent Review articles by Jody W. Lipford | ||

| Summer 2021 | A Fiscal Cliff: New Perspectives on the U.S. Federal Debt Crisis | |

| Summer 2020 | Is the Welfare State Crowding Out Government’s Basic Functions?: An Update | |

| Spring 2018 | Who Is the Forgotten Man (and Woman) on the Fiscal Commons? | |

| [View All (9)] | ||