The accepted wisdom is that private schools serve the privileged; everyone else, especially the poor, requires public school. The poor, so this logic goes, need government assistance if they are to get a good education, which helps explain why, in the United States, many school choice enthusiasts believe that the only way the poor can get the education they deserve is through vouchers or charter schools, proxies for those better private or independent schools, paid for with public funds.

But if we reflect on these beliefs in a foreign context and observe low-income families in underprivileged and developing countries, we find these assumptions lacking: the poor have found remarkably innovative ways of helping themselves, educationally, and in some of the most destitute places on Earth have managed to nurture a large and growing industry of private schools for themselves.

For the past two years I have overseen research on such schools in India, China, and sub-Saharan Africa. The project, funded by the John Templeton Foundation, was inspired by a serendipitous discovery of mine while I was engaged in some consulting work for the International Finance Corporation, the private finance arm of the World Bank. Taking time off from evaluating an elite private school in Hyderabad, India, I stumbled on a crowd of private schools in slums behind the Charminar, the 16th-century tourist attraction in the central city. It was something that I had never imagined, and I immediately began to wonder whether private schools serving the poor could be found in other countries. That question eventually took me to five countries—Ghana, Nigeria, Kenya, India, and China—and to dozens of different rural and urban locales, all incredibly poor. Since the data gathered from Lagos, Nigeria, and Delhi, India, are not yet fully analyzed, this article reports on findings only from Gansu Province, China; Ga, Ghana; Hyderabad, India; and Kibera, Kenya. These are in vastly different settings, but my research teams and I found large numbers of private schools for low-income families, many of which showed measurable achievement advantage over government schools serving equally disadvantaged students.

Myth One: Private Education for the Poor Does Not Exist

Undertaking this research was disheartening at first. In each country I visited, officials from national governments and international agencies that donate funds for the expansion of state-run education denied that private education for the poor even existed. In China senior officials told me that what I was describing was “logically impossible” because “China has achieved universal public education and universal means for the poor as well as the rich.” At other times, in other places, I met with polite, if embarrassed, apologies that always went something like, “Sorry, in our country, private schools are for the privileged, not the poor.”

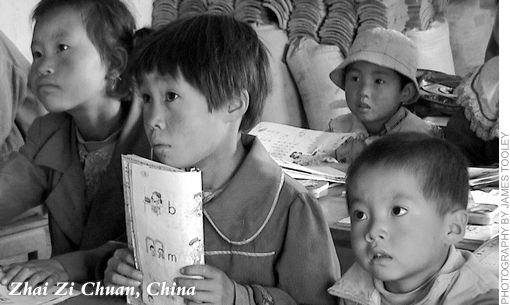

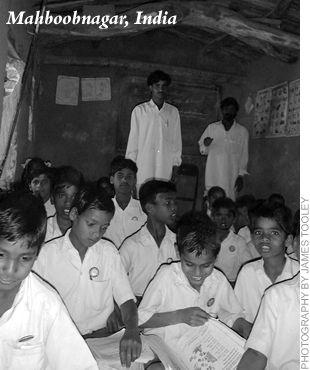

In each venue, however, I struck out on my own and visited slums and villages and there found what I was looking for: private schools for the poor, usually in large numbers, if sometimes hidden from view. In the slums of Hyderabad, India, a typical private school would be in a converted house, in a small alleyway behind bustling and noisy streets, or above a shop. Classrooms are dark, by Western standards, with no doors hung in the doorways, and noise from the streets outside easily entering through the barred but unglazed windows. Walls are painted white, but discolored by pollution, heat, and the general wear-and-tear of the children; no pictures or work is hung on them. Children will usually be in a school uniform and sitting at rough wooden desks. Generally, there are about 25 students in a class, a decent teacher-to-student ratio, but the tiny rooms always seem crowded. Often the top floor of the building will have various construction work going on to extend the number of classrooms. The school proprietor will usually live in a couple of rooms at the back of the building.

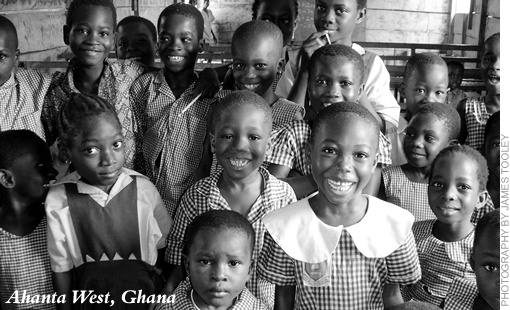

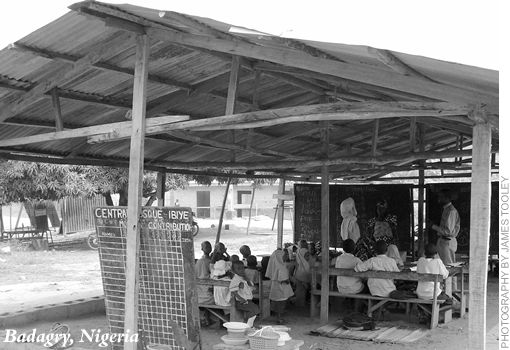

In rural Ghana, a typical private school might consist of an open-air structure, often no more than a tin roof supported by wooden poles, on a small plot of land. To find these schools you’ll have to wander down meandering narrow paths, away from the main thoroughfares, asking villagers as you go. If you ask simply for the “school,” they’ll send you back to the public school, usually an impressive brick building on the main road. You’ll have to persist and say you want the “small” school to get directions.

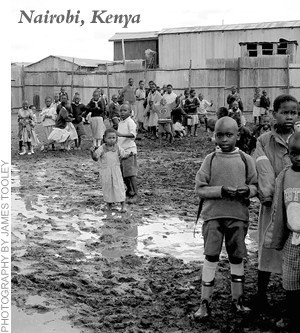

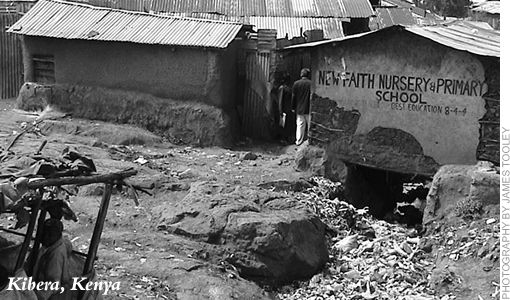

In the slums of Nairobi, Kenya, private schools are made from the same materials as every other building: corrugated iron sheets or mud walls, with windows and doors cut out to allow light to enter. Floors are usually mud, roofs sometimes thatched. Children will not be in uniform and will usually be sitting on homemade wooden benches. In the dry season, the wind will blow dust through the cracks in the walls; in the rainy season, the playground will become a pond, and the classroom floors mud baths. Teaching continues, however, through most of these intemperate interruptions.

In the slums of Nairobi, Kenya, private schools are made from the same materials as every other building: corrugated iron sheets or mud walls, with windows and doors cut out to allow light to enter. Floors are usually mud, roofs sometimes thatched. Children will not be in uniform and will usually be sitting on homemade wooden benches. In the dry season, the wind will blow dust through the cracks in the walls; in the rainy season, the playground will become a pond, and the classroom floors mud baths. Teaching continues, however, through most of these intemperate interruptions.

In order to conduct research in five countries from my base in Newcastle, England, I recruited teams of researchers from reputable local universities and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). While fielding the research crews, I visited dozens of likely study sites, always in low-income areas, and always found private schools for the poor. I also visited government offices to gain permission to conduct the research. In the end, all of the chosen countries, apart from China, were rated by the Oxfam Education Report as countries where education needs were not being met by government systems. Though China is ranked relatively high on the Oxfam index, we wanted to include it in our study because of the dramatic political and economic changes there in the past several decades. (Because of the threat of SARS, however, our first research team spent a long period in quarantine and thus our research there is not yet complete.) Other countries were chosen for a mixture of practical and substantive reasons. I was particularly interested in Kenya, where free elementary education had just been introduced to much acclaim. How would this affect private schools for the poor, should they exist? I had conducted research earlier in Hyderabad, India, was familiar with the terrain, and had many contacts in government and the private sector, so it seemed sensible to continue the project there. And because of a chance meeting with the Ghanaian minister of education at a conference in Italy, we were invited to that western African nation.

Many difficulties emerged that I had not taken account of as the project progressed. Heavy rains prevented the research teams from moving around in both Ghana and Nigeria for weeks at a time; intense heat delayed work for days in Hyderabad; early snowfalls hampered movement in the mountains of China. But above all, a major difficulty was getting the extended research teams to take seriously the notion that we really were interested in the low-key, unobtrusive private schools that apparently were easily dismissed. In each of the settings, on unannounced quality control visits, I found unrecognized private schools that had not been reported by the teams.

Hyderabad, India

Visit the ultramodern high-rise development of “High Tech City” and you’ll see why Hyderabad dubs itself “Cyberabad,” proud of its position at the forefront of India’s technological revolution. But cross the river Musi and enter the Old City, with once magnificent buildings dating to the 16th century and earlier, and you’ll see the congested India, with narrow streets weaving their way through crowded markets and densely populated slums. For our survey, we canvassed three zones in the Old City (Bandlaguda, Bhadurpura, and Charminar), with a population of about 800,000 (about 22 percent of all of Hyderabad), covering an area of some 19 square miles. We included only schools that were found in “slums,” as determined by the latest available census and Hyderabad municipal guides, areas that lacked amenities such as indoor plumbing, running water, electricity, and paved roads.

In these areas alone our team found 918 schools: 35 percent were government run; 23 percent were private schools that had official recognition by the government (“recognized”); and, incredibly, 37 percent slipped under the government radar (“unrecognized”). The last group is, in effect, a black market in education, operating entirely without both state funding and regulation. (The remaining 5 percent were private schools that received a 100 percent state subsidy for teachers’ salaries, making them public schools in all but name.) In terms of total student enrollment in the slum areas of the three zones, with 918 schools, 76 percent of all schoolchildren attended either recognized or unrecognized private schools, with roughly the same percentage of children in the unrecognized private schools as in government schools (see Figure 1).

SOURCE: Author’s calculations based on original research and local government figures.

SOURCE: Author’s calculations based on original research and local government figures. |

What is clear from our research is that these private schools are not mom-and-pop day-care centers or living-room home schools. The average unrecognized school had about 8 teachers and 170 children, two-thirds in rented buildings of the type described above. The average recognized school was larger and usually situated in a more comfortable building, with 18 teachers and about 490 children. Another key difference between the recognized and unrecognized schools is that the former have stood the test of time in the education market: 40 percent of unrecognized schools were less than 5 years old, while only 5 percent of recognized schools were this new. Finally, tuition in these schools is very low, averaging about $2.12 per month in recognized private schools at 1st grade and $1.51 in unrecognized schools.

While these fees seem extremely low, they must be measured against the average income of each person in the student’s household who is working for pay. For students in unrecognized schools, this was about $23 per month, compared with about $30 per month for students in recognized schools and $17 for government schools. Since the official minimum wage in Hyderabad is $46 per month, it is clear that the families in the private schools we observed are poor. Fees amount to about 7 percent of average monthly earnings in a typical household using a private unrecognized school. For the poorest children, the schools provide scholarships or subsidized places: 7 percent of children paid no tuition and 11 percent paid reduced fees. In effect, the poor are subsidizing the poorest.

Ga, Ghana

The Ga district of southern Ghana, which surrounds the country’s capital city of Accra, is classified by the Ghana Statistical Service as a low-income, urban periphery, and rural area. With a population of about 500,000, Ga includes poor fishing villages along the coast, subsistence farms inland, and large dormitory towns for workers serving the industries and businesses of Accra itself. Most of the district lacks basic social amenities such as potable water, sewage systems, electricity, and paved roads. In Ga’s towns and villages our researchers found a total of 799 schools, 25 percent of which were government, 52 percent recognized private, and 23 percent unrecognized private. In total, 33,134 children were found in unrecognized private schools, or about 15 percent of children enrolled in school (see Figure 2).

The average monthly fee for an unrecognized private school in Ga is about $4 for the early elementary grades, about $7 in recognized schools. With a minimum wage of about $33 per month in the area, monthly fees in the private unrecognized schools are thus about 12 percent of the average monthly earnings of an adult earner. However, many of the poorest schools allow a daily fee to be paid so that, for instance, a poor fisherman could send his daughter to school on the days he had funds and allow her to make up for the days she missed. Such flexibility is not possible in the public schools, where full payment of the “levies” is required before the term starts. (Fees for “public” schools are common in many countries throughout the Third World, especially at high-school level. Thus the cost of private schools, we found, can sometimes be less than that of government ones.)

Unlike India, where there are restrictions on private-school ownership (private schools must be owned by a society or trust), in Ga the vast majority of private schools (82 percent of recognized and 93 percent of unrecognized) are run by individual proprietors; most of the rest are owned and managed by charitable organizations. Sometimes, as is common in other African countries, such schools rent church buildings or use Christian-related names, but only in a few cases are the schools run by churches. Often it is the school that subsidizes the church rather than the other way around!

Gansu, China

With 25.3 million people spread out over an area the size of Texas, Gansu province is a remote and mountainous region situated on the upper and middle reaches of the Yellow River in northwest China. It has an average elevation of over 3,000 feet and 75 percent of its population is rural, with illiteracy rates among people aged 15 or older at nearly 20 percent for men and 40 percent for women. Roughly half of its counties, with 62 percent of the population, are considered “impoverished.”

Figures from the Provincial Education Bureau show only 44 private schools in the whole province, all of which are for privileged city dwellers. Given the paucity of information on private schools, I asked my research teams to survey each major town in each of the counties designated as impoverished (more than 40 of them) and to visit as many of the outlying villages accessible to them as they could. In the early stages I wasn’t worried about getting precise estimates of the numbers of schools or the proportion of children in them, but rather wanted to see if such schools even existed.

In the major towns and the larger villages, all of them crowded and bustling, there is always a public school, usually a fine two-story building that sports a plaque marking it as a recipient of some kind of foreign aid. But researchers had to abandon their cars and either walk or hitch a ride on one of the ubiquitous and noisy three-wheeled farm vehicles to travel up the steeper mountain paths to clusters of houses in smaller villages to find the private schools. And there, nestled on mountain ridges, were stone or brick houses converted to schools, with the proprietor or headmaster living with his family in one or two of its rooms. Occasionally, the school had been built, by the villagers, to be used as a school. Over and over again, researchers followed these trails high into the arid mountains and, in the end, discovered a total of 696 private schools, 593 of them serving some 61,000 children in the most remote villages.

Not surprisingly, the vast majority of Gansu’s private schools were set up by individuals, or the villages themselves, because government schools are simply too far away or hard to get to. Significantly, the majority of the private schools found were in the three poorest regions of Gansu, where average net income per year ranges from $125 to $166. These private schools are serving some of the poorest people on the planet. But surprisingly, the schools, which depend on tuition, are also cheaper than government schools. Average fees for a first-year, elementary-school student are about $7.60 per semester, compared with about $8.00 in the public schools, not an insignificant difference to someone living on $125 per year.

Kibera, Kenya

In Kenya we conducted our censuses in three urban slums of Nairobi (Kibera, Mukuru, and Kawangware), where, according to Kenyan government officials, there were no private schools. The picture in each was similar; here I describe the findings for Kibera only.

The largest slum in all of sub-Saharan Africa, Kibera has, according to various estimates, anywhere from 500,000 to 800,000 people crowded into an area of about 630 acres, smaller than Manhattan’s Central Park. Mud-walled, corrugated iron-roofed settlements huddle along the old Uganda Railway for several miles and crowd along steep narrow mud tracks until Kibera reaches the posh suburbs. In Nairobi’s two rainy seasons, the mud tracks become mud baths. In this setting, we found 76 private elementary and high schools, enrolling more than 12,000 students. The schools are typically run by local entrepreneurs, a third ofwhom are women who have seen the possibility of making a living from running a school. Again, many of the schools offered free places to the poorest, including orphans.

When I first visited Kibera, many private-school proprietors were feeling the effects of so-called Free Primary Education (FPE), introduced by the Kenyan government in January 2003 with great fanfare and a $55 million grant from the World Bank. In fact, when asked by ABC anchorman Peter Jennings which one living person he would most like to meet, former president Bill Clinton told a prime-time television audience that it was President Mwai Kibaki of Kenya, “Because he has abolished school fees,” which “would affect more lives than any president had done or would ever do by the end of this year.” Indeed, official sources estimated that an extra 1.3 million children would be enrolled in public schools after the introduction of FPE: all of them children, it was said, not previously enrolled in school.

The reality may be very different. Private-school owners in Kibera alone reported a total enrollment decline of some 6,500 after Free Primary Education was initiated; some schools closed altogether. We estimated that about 4,500 children had been enrolled in 25 schools that we confirmed had closed as a result of FPE. At the same time five government primary schools on the periphery of Kibera that served the slums reported a total increase of only about 3,300 children during this period. That is, since the introduction of free elementary education, there appeared to have been a net decline in attendance of nearly 8,000 children from one slum alone! Clearly, these figures are based on the reported decline by school owners and may be exaggerated. But they also suggest the possibility that government and international intervention had the effect of crowding out private enterprise.

Myth TWO: Private Education for the Poor Is Low Quality

It is a common assumption among development experts that private schools for the poor are worse than public schools. This is not to say that they have a particularly high view of public education. Indeed, the World Bank’s World Development Report 2004: Making Services Work for Poor People calls public education a “government failure,” with “services so defective that their opportunity costs outweigh their benefits for most poor people.” Yet this just makes the experts’ dismissal of private schools for the poor all the more inexplicable.

The Oxfam Education Report published in 2000 is typical. While the author acknowledges the existence of high-quality private providers, he contends that these are elite, well-resourced schools that are inaccessible to the poor. As far as private schools for the poor are concerned, these are of “inferior quality”; indeed, they “offer a low-quality service” that is so bad it will “restrict children’s future opportunities.” This claim of low-quality private provision for the poor has also been taken up by British prime minister Tony Blair’s Commission for Africa, which recently reported that although “Non-state sectors ... have historically provided much education in Africa,” many of these private schools “aiming at those [families] who cannot afford the fees common in state schools ... are without adequate state regulation and are of a low quality.”

However, these development experts have little hard evidence for their assertions about private-school quality. They instead point out that private schools employ untrainedteachers who are paid much less than their government counterparts and that buildings and facilities are grossly inadequate. Both of these observations are largely true. But does that mean that private schools are inferior, particularly against the weight of parental preferences to the contrary? One Ghanaian school owner challenged me when I observed that her school building was little more than a corrugated iron roof on rickety poles and that the government school, just a few hundred yards away, was a smart new school building. “Education is not about buildings,” she scolded. “What matters is what is in the teacher’s heart. In our hearts, we love the children and do our best for them.” She left it open, when probed, what the teachers in the government school felt in their hearts toward the poor children.

Facilities and Resources

The issue of the relative quality of private and public schools was at the core of our research, and we relied on both data on school resources and day-to-day operations and on student achievement scores. Our researchers first called unannounced at schools and asked for a tour, noted what teachers were doing, made an inventory of facilities, and administered detailed questionnaires.

Certainly, in some countries the facilities in the private schools were markedly inferior to those in the public schools. In China, where the researchers were asked to locate a public school in the village nearest to where they had found a private school, often many miles away, private-school facilities were generally worse than in those publicly provided. This was predictable, given that the private schools undercut the public ones in fees and served the poorest villages, where there were no public schools. In Gansu province, desks were available in classrooms in 88 percent of private schools, compared with 97 percent of public schools; 66 percent of private schools had chairs or benches in classrooms, compared with 76 percent of public schools. In Kenya, parallel results would be expected, given that the private schools surveyed were located in the slums, while the public schools were on the periphery, accommodating both poor and middle-class children. However, given that there were only 5 government schools on the periphery of Kibera, but 76 private schools within the slum, statistical comparisons would make little sense.

In Hyderabad, however, on every input, including the provision of blackboards, playgrounds, desks, drinking water, toilets, and separate toilets for boys and girls, both types of private schools, recognized and unrecognized, were superior to the government schools. While only 78 percent of the government schools had blackboards in every classroom, the figures were 96 percent and 94 percent for private recognized and unrecognized schools, respectively. In only half the government schools were toilets provided for children, compared with 100 percent and 96 percent of the recognized and unrecognized private schools.

Finally, in Ghana, the picture is mixed. For instance, 95 percent of government schools in Ga had playgrounds, compared with 66 percent and 82 percent of private unrecognized and recognized schools, respectively. Desks were provided in 97 percent of government schools, but only in 61 percent of private unrecognized; recognized private schools provided them in 92 percent of cases. However, only 54 percent of government schools provided drinking water to children compared with 63 percent of private unrecognized and 87 percent of private recognized schools. And 63 percent of government schools provided toilets, compared with 91 percent of recognized but only 59 percent of unrecognized private schools. A library was provided in 8 percent of government, 7 percent of private unrecognized schools, but 27 percent of private recognized schools. At least one computer for the use of children was provided in only 3 percent of government schools, but in 12 percent of private unrecognized and 37 percent of private recognized.

When it came to the key question of whether or not teaching was going on in the classrooms, both types of private schools were superior to the public schools, except in China, where there was no statistically significant difference between the two school types: 92 percent of teachers in private schools were teaching when our researchers arrived, compared with 89 percent in the public schools. When researchers called unannounced on the classrooms in Hyderabad, 98 percent of teachers were teaching in the private recognized schools, compared with 91 percent in the unrecognized and 75 percent in the government schools. Teacher absenteeism was also highest in the government schools. In Ga, 57 percent of teachers were teaching in government schools, compared with 66 percent and 75 percent in unrecognized and recognized private schools, respectively. And in Kibera, even though the number of government schools is too small to make statistical comparisons meaningful, 74 percent of teachers were teaching in private schools when our researchers visited them, and only one teacher was absent.

It was also the case that private and public schools in China had more or less the same pupil-teacher ratio, about 25:1. In Hyderabad, private schools, including the unrecognized ones, had significant advantages over the government schools: the average pupil-teacher ratio was 42:1 in government schools compared with only 22:1 in the unrecognized and 27:1 in the recognized private schools. In Ga the pupil-teacher ratio was superior in private schools, with a ratio of 29:1 in government, compared with 21:1 and 20:1 in unrecognized and recognized private schools, respectively.

Student Achievement

To compare the achievement of students in public and private schools in each location where we conducted research, we first grouped schools by size and management type: government, private unrecognized, and private recognized in Ga and Hyderabad; government and private in Kibera, where the private schools are all of a similar type. (China is not discussed here because research there is continuing.) As noted above, in Ga and Hyderabad we were comparing public and private schools that were located in similar, low-income areas, while in Kibera, private schools served only slum children, and public schools served middle-class children as well as slum children. But this makes the comparisons in Kenya even more dramatic. Although serving the most disadvantaged population in the region, Kibera’s private schools outperformed the public schools in our study, after controlling for background variables.

To compare the achievement of students in public and private schools in each location where we conducted research, we first grouped schools by size and management type: government, private unrecognized, and private recognized in Ga and Hyderabad; government and private in Kibera, where the private schools are all of a similar type. (China is not discussed here because research there is continuing.) As noted above, in Ga and Hyderabad we were comparing public and private schools that were located in similar, low-income areas, while in Kibera, private schools served only slum children, and public schools served middle-class children as well as slum children. But this makes the comparisons in Kenya even more dramatic. Although serving the most disadvantaged population in the region, Kibera’s private schools outperformed the public schools in our study, after controlling for background variables.

We tested a total of roughly 3,000 students in each setting in English and mathematics; in state languages in India and Kenya; religious and moral education in Ghana; and social studies in Nigeria. All children were also given IQ tests, as were their teachers. Finally, questionnaires were distributed to children, their parents, teachers, and school managers, seeking information on family backgrounds.

Our analysis of these data is still in progress. However, in all cases analyzed so far—Ga, Hyderabad, and Kibera—students in private schools achieved at or above the levels achieved by their counterparts in government schools in both English and mathematics (see Figure 3).

SOURCE: Author’s calculations based on original research and local government figures |

Moreover, the private-school advantage only increases with consideration of the differences in an unusually rich array of characteristics of the students, their families’ economic status, and the resources available at their schools. In Hyderabad, students attending recognized and unrecognized private schools outperformed their peers in government schools by a full standard deviation in both English and math (after accounting for differences in their observable characteristics). In Ghana, the adjusted private-school advantagewas between 0.2 and 0.3 standard deviations in both subjects. Finally, in Kenya, where the raw test scores showed students in private and public schools performing at similar levels, the fact that private schools served a far more disadvantaged population resulted in a gap of 0.1 standard deviations in English and 0.2 standard deviations in math (after accounting for differences in student characteristics). The adjusted differences between the performance of public and private sectors in each setting were highly statistically significant.

In short, it is not the case that private schools serving low-income families are inferior to those provided by the state. In all cases analyzed, even the unrecognized schools, those that are dismissed by the development experts as being obviously of poor quality seem to outperform their public counterparts.

Lessons for America

So the accepted wisdom appears to be wrong. Though elite private schools do exist in impoverished regions of the world, private schools are not only for the privileged classes. From a wide range of settings, from deepest rural China, through the slums of urban India and Kenya, to the urban periphery areas o Ghana, private education is serving huge numbers of children. Indeed, in those areas where we were able to adequately compare public and private provision, a large majority of schoolchildren are in private school, a significant number of them in unrecognized schools and not on the state’s radar at all.

Ironically, perhaps, the accepted wisdom does seem to be right on one point: private is better than public. Of course, no one suspected that private slum schools would be better. Yet our research suggests that children in these schools outperform similar students in government schools in key school subjects. And this is true even of the unrecognized private schools, schools that development experts dismiss, if they acknowledge their existence at all, as being of poor quality.

Clearly the evidence presented here may have implications for the continuing policy discussions over how to achieve universal education worldwide and for American development policy, especially programs of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the World Bank. William Easterly, in his Elusive Quest for Growth (see also “Barren Land,” Fall 2002), notes the ineffectiveness of past investments in public schools by the international agencies and developing country governments, pointing out: “Administrative targets for universal primary education do not in themselves create the incentives for investing in the future that matter for growth,” that is, in quality education. If the World Bank and USAID could find ways to invest in private schools, then genuine education improvement could result. Strategies to be considered include offering loans to help schools improve their infrastructure or worthwhile teacher training, or creating partial vouchers to help even more of the poor gain access to the private schools that are ready to take them on.

But does the evidence have any implications for the school choice debate in America itself? The evidence from developing countries might challenge the claim, made by school choice opponents, that the poor in America cannot make sensible and informed choices if school choice is offered to them. It may also stimulate debate about whether public intervention crowds out private initiative, a question raised by the findings from Kenya.

If a public school is failing in the ghettoes of New York or Los Angeles, we should not assume that the only way in which the disadvantaged can be helped is through some kind of public intervention. In fact, we have already embarked on programs that support private initiative, with government support, with vouchers and charter schools. The findings here suggest this alternative approach may be the preferable one.

Above all, the evidence should inspire those who are working for school choice in America: stories of parents’ overcoming all the odds to ensure the best for the children in Africa and Asia, stories of education entrepreneurs’ creating schools out of nothing, in the middle of nowhere. If India can, why can’t we?