The U.S. Department of Justice and several states have chosen to settle their antitrust case against Microsoft but nine states—led by California and Connecticut—have chosen to fight on. And unless some agreement between the parties is reached soon, which is unlikely, still another trial against Microsoft will begin in U.S. District Court in early March, 2002.

Antitrust cases are a notorious legal and economic mess, but this decade-long monstrosity pushes the absolute limits of absurdity. The seeds of the current difficulties actually go back to Federal Trade Commission investigations, begun in 1990, of Microsoft’s software licensing agreements. The FTC never filed charges against Microsoft, yet a year later, the Justice Department began its own investigation of Microsoft’s alleged unfair business practices. It finally concluded Microsoft’s standard software lease agreements restricted competition (read: competitors) and it bullied Microsoft into signing a consent decree in 1994 which, among other things, shortened the standard two-year leasing period to one year.

With the rising popularity of the World Wide Web, Microsoft’s legal difficulties increased many-fold. When Microsoft introduced Windows 95 in late 1994, it shrewdly decided to integrate its Web browser, Explorer, with its new Windows operating system. An integrated browser was easier and cheaper for consumers to use and was a formidable competitor with the then-industry leader, Netscape. The Justice Department, in an unprecedented move, first attempted to delay the introduction of Windows 95. Failing that, it claimed the integrated browser violated its 1994 consent decree with Microsoft. An Appellate Court ruled definitively in Microsoft’s favour on this integration issue in June, 1998, but in the interim, the Justice Department and 20 states sued Microsoft under the Sherman Antitrust Act and a trial began in October, 1998.

After a long and contentious courtroom drama, Judge Thomas Penfield Jackson found Microsoft guilty in November, 1999, and ordered the company’s divestiture as a remedy. But in a ruling that shocked the antitrust world, the U.S. Court of Appeals unceremoniously discarded the guts of the government’s suit (as well as the entire Jackson remedy) in June, 2001. The appeals court unanimously rejected the governments’ primary contention, namely, that Microsoft had illegally tied its Web browser to its operating system. Unfortunately, however, the appeals court let stand several of Judge Jackson’s misguided "findings of fact" concerning monopoly and restraint of trade and left open the option of a return trip to a court for legal resolution.

Although the Department of Justice and several states have chosen to settle with Microsoft, nine other states chose to litigate the remaining issues. In its settlement with the Department of Justice, Microsoft agreed to end exclusive dealing with original equipment manufacturers (OEMs), charge OEMs published rates with uniform discounts, and open its "source code" to applications developers.

So what can the holdout states (or, more accurately, their consumers) hope to gain from any continued litigation? Not much. The states have already identified several witnesses who will testify, and it appears the new trial will be a virtual replay of the old one. The states will march several of Microsoft’s traditional competitors (including Jim Barksdale, former CEO of Netscape) to the stand, as well as a slew of new competitors, such as Palm and Nokia. They undoubtedly will whine that Microsoft’s behaviour continues to threaten their particular product or service, and that additional curbs on Microsoft’s business practices are justified in the name of preserving competition.

But since the Justice Department was unable to negotiate such curbs in its consent decree with Microsoft, what makes the states think some new judge will legitimize any new restrictions?

Indeed, aside from enriching lawyers and enhancing the public visibility of state attorneys general, this continued litigation will serve no legitimate public purpose. The bulk of the complaints concerning Microsoft’s behaviour have always related to Microsoft’s formidable innovation skills and aggressive marketing of product. The first trial produced not one shred of evidence Microsoft’s software licensing or browser integration resulted in any consumer injury; the new trial will be similarly cursed. Instead, the testimony will confirm Microsoft plays competitive hardball (who doesn’t?) and intends to take market share from competitors with new innovation, savvy marketing and low prices.

But that kind of behaviour (engaged in by all free market firms) is the very nature of the competitive process and should be applauded, not condemned. Yet the holdout states and their politically ambitious attorneys general falsely believe antitrust laws exist to preserve specific competitors or specific products and that government must constantly level the playing field or micro-manage inter-firm business dealings with antitrust litigation. So the states will put the competitors on the stand and let them whine.

Consumers (and businesses) in all states require government protection from force and fraud but they don’t require decade-long antitrust assaults on firms that innovate and lower prices to consumers. Such assaults are economically inefficient, create incentives for additional litigation, perpetuate business uncertainty and harm society’s long-term welfare. Enough already.

It’s Time to Quit

Also published in National Post

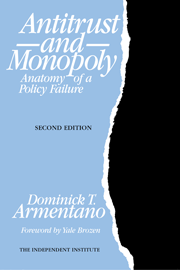

Dominick T. Armentano is a Research Fellow at the Independent Institute and professor emeritus in economics at the University of Hartford (CT).

Comments

Before posting, please read our Comment Policy.