According to calendar makers, the twentieth century began on January 1, 1901 and ended one hundred years later. But a historical case can be made that it began on June 28, 1914, when Gavrilo Princip murdered Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand and ended on December 25, 1991 when the hammer and sickle flag of the Soviet Union was lowered from the Kremlin for the last time. In this reading, the twentieth century was marked by the rise of communism—triggered by the war that Princip sparked—and its rapid demise from 1989 to 1991.

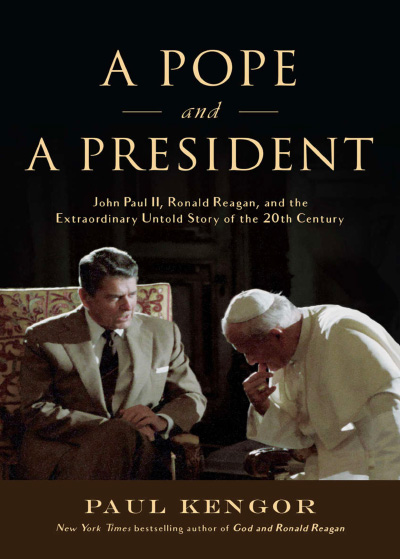

Paul Kengor (political scientist at Grove City College) argues that the extraordinary untold story of the twentieth century was the heroic collaboration between a pope and a president which brought about the death of Soviet communism. Much has been written about the crucial roles of John Paul and Reagan in causing the collapse of the “Evil Empire.” But the “untold” story is the nature of the partnership between these two men. The bond between them arose after each was shot in early 1981. Both came perilously close to death and both believed that they had been saved by divine providence so that they could accomplish a sacred mission—the defeat of atheistic communism. (Reagan even had a code name for it. In private conversations he frequently spoke of the “DP”—the divine plan to take down communism.) Inflamed by this shared belief, they worked tirelessly to defeat communism primarily by revealing to the world its utter evil. They undermined its legitimacy in the minds and hearts of those living on both sides of the Iron Curtain—strengthening the resolve of anti-communists in the West as well as those living under its yoke in the East, but also weakening the resolve of the taskmasters who had imposed the yoke. These ideas fanned a gale that ultimately blew down the rickety communist structure.

A Pope and A President documents the deep friendship that emerged between John Paul and Reagan, each of their meetings, and the steady volume of the communication between them between meetings. But the dearest part of the untold story from Kengor’s point of view is the role played in this relationship by the Virgin Mary. Pope John Paul II credited her with saving his life from assassin Mehmet Ali Agca’s bullet. That assassination attempt occurred on May 13, 1981, a date of no significance to most people, but John Paul knew that May 13 was the anniversary of the first apparition of the Virgin by three children in Fatima, Portugal in 1917 and that these visionaries believed that three secrets were revealed to them. One of the secrets was that World War I would soon end but unless Russia was converted, it would spread its errors throughout the world. The third secret was unknown to John Paul at the time of the shooting, but he soon learned that this was a vision of an assassination attempt on a bishop—a vision that he took as being fulfilled in him, something that was verified by one of the visionaries. As Kengor notes, even if one doesn’t put any stock in these supernatural events, because the pope did they helped shape history since he responded by devoting himself to the mission of defeating communism. The other protagonist of the story, the Protestant Reagan, also developed a deep veneration of Mary and Our Lady of Fatima became a bond between the two men. The wind that blew down the Soviet straw house was the wind of the Holy Spirit in the minds of these men.

Had they known how effective Reagan and John Paul would be in destroying their system, the Soviets would probably have tried to kill them. And, as Kengor documents, they were ultimately behind the near assassination of the pope. The surprise is that they weren’t more persistent, perhaps because they underestimated the peril they faced.

Reading A Pope and a President, one is reminded that the defeat of Soviet communism was a very noble task because the USSR was unquestionably an evil empire. Its evils are well documented in some of the contributions to The Independent Review’s current symposium on the 100th Anniversary of the Russian Revolution, especially Yuri Maltsev’s “Mass Murder and Public Slavery: The Soviet Experience.” Kengor chronicles the evil by focusing on its zealous religious persecution. One mind-numbing chapter, “The Devil Takes Over,” recounts the mass murder of believers in the Soviet Union in the 1920s and 30s and the wholesale looting, destruction and desecration of their churches—with nuns being forced into houses of prostitution. Another chapter narrates the “dry martyrdom of Cardinal Mindszenty,” the primate of the Catholic Church in Hungary, who was tortured, convicted in a show trial, granted political asylum in the U.S. embassy and finally died in exile in 1975. During the Reagan years, Western allies of communism claimed that these excesses had disappeared—but then they were confronted by the brutal martyrdom of Father Jerzy Popiełuszko, who fearlessly advised the Solidarity movement in Poland. (Father Jerzy Popiełuszko seems to have foreseen the events that unfolded shortly after his death, saying that “an idea that needs rifles to survive will die on its own accord” (p. 367).) Just as important, Kengor also documents the Soviets’ clever and relentless disinformation tactics meant to cover up their own crimes and undermine religious authority, such as their invention and dissemination of the blatant lie that somehow Pope Pius XII had been a friend of the Nazis during World War II.

The volume makes clear that Reagan’s political views were grounded in his religious views. When greeting John Paul during a visit to the U.S. in 1987, Reagan put it this way: “The Founding Fathers were neither metaphysicians nor theologians, but their philosophy of life and their political philosophy, their notion of natural law and of human rights, were permeated with concepts worked out by Christian reason and backed up by an unshakeable religion feeling. From the first, then, our nation embraced the belief that the individual is sacred and that as God himself respects human liberty, so, too must the state” (p. 455-56). Freedom is a blessing from God—and Reagan spoke about this freedom and these blessings far and wide—especially when he went behind the Iron Curtain. He did this despite the objections of the State Department and the embarrassment of the much of the press. But Kengor shows how eagerly these words were heard in the Eastern Bloc. Being leader of the free world gives you quite a stage and Reagan used the stage to offer benedictions, learning to say “Da blagoslovit vas gospod” (God bless you) to his Russian audience.

One question nagged at me as I read this volume. Why didn’t the American left support Reagan in his push against communism? The mainstream left supported Truman’s and Kennedy’s anti-communism but insisted that Reagan was a warmonger, bent on triggering a military confrontation with Moscow. In hindsight, the Reagan military buildup helped force the Soviets’ hand, led to a historical treaty to reduce nuclear weapons, accelerated the demise of the USSR, and saved U.S. taxpayers an immense amount in the next decade’s peace dividend. This may have been hard to predict, but why not mere skepticism toward this agenda rather than outright hostility, derision and palpable misinterpretation? Sheer politics? Econ Journal Watch recently held a symposium on “My Most Regretted Statements,” in which academics explained mistakes they’d made in the past and why they’d made them. I was most impressed (distressed?) with what Jon Elster, a noted proponent of analytical Marxism, had to say. He wrote: “Until around 1990 [i.e. during Reagan’s assault on communism] I believed, with most of my friends, that on a scale of evil from 0 to 10 (the worst), Communism scored around 7 or 8. Since the recent revelations I believe that 10 is the appropriate number. The reason for my misperception of the evidence was not an idealistic belief that Communism was a worthy ideal that had been betrayed by actual Communists ... Rather, I was misled by the hysterical character of those who claimed all along that Communism scored 10. My ignorance of their claims was not entirely irrational. On average, it makes sense to discount the claims of the manifestly hysterical. Yet even hysterics can be right, albeit for the wrong reasons. Because I sensed and still believe that many of these fierce anti-Communists would have said the same regardless of the evidence, I could not believe that what they said did in fact correspond to the evidence” (Jon Elster, 2017, “My Most Regretted Statements,” Econ Journal Watch, 14, no. 2: 286-87). This is the mindset that Reagan encountered. You are hysterical. I know that you’re hysterical because you are so fervently anti-Communist. Therefore, I don’t believe you and won’t even look at the evidence you cite. This is a sad warning that suggests that everyone (left, right and center) needs to look at evidence and not reflexively make their enemy’s enemies into their own friends. It also reminds us that the messenger is crucial. If one appears to be “hysterical,” even if correct, the truth may be ignored. It turns out that Reagan came across as hysterical to some and some of his comments—such as his hot mike joke (not reported in Kengor’s hagiography): “My fellow Americans, I'm pleased to tell you today that I've signed legislation that will outlaw Russia forever. We begin bombing in five minutes”—undermined his cause. The same cannot be said of John Paul, but he too was selling something that people on the left thought was meaningless, if not hysterical.

Freedom is what both the pope and the president preached—and the first of these freedoms in their eyes was religious freedom. But freedom is not free and freedom—like all other good things—is easy to misunderstand and misrepresent. John Paul II solemnly warned that “Freedom is at the same time offered to man and imposed upon him as a task” (p. 158).

| Other Independent Review articles by Robert M. Whaples | ||

| Spring 2024 | A Vision of a Productive Free Society: Murray Rothbard’s For a New Liberty | |

| Spring 2024 | GOAT: Who Is the Greatest Economist of All Time and Why Does It Matter? | |

| Spring 2024 | Everyday Freedom: Designing the Framework for a Flourishing Society | |

| [View All (93)] | ||