Few civil rights leaders confronted Jim Crow more effectively before the rise of Martin Luther King Jr. than T.R.M. Howard (1908-1976). His commanding presence and impressive achievements made him hard to ignore. A respected surgeon, Howard was one of the wealthiest African Americans in Mississippi and headed a successful mass movement for equality under the law.

From the beginning, armed self-defense was as an essential component of the struggle.

Guns were always a key feature of Howard’s life ever since his impoverished childhood in rural Kentucky. Every Sunday his mother gave him a quarter to buy four gun shells. Her instructions were to return with either two rabbits or two squirrels, or one of each, for the dinner table. But the Howard family understood that guns were not just for getting food. They would have agreed with anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells who, in the 1890s, after blacks in nearby Paducah used guns to drive off attackers, advised that “a Winchester rifle should have a place of honor in every black home, and it should be used for that protection which the law refuses to give.”

In 1942, Howard became chief surgeon at the Taborian Hospital in the all-black town of Mound Bayou, Miss., which gave affordable care with no government aid. He soon founded an insurance company, a hospital, a home construction firm, and a 1,000-acre plantation where he raised cattle, quail, hunting dogs, and cotton. He also built a small zoo and a park, as well as the first swimming pool in Mississippi for blacks.

Howard entered the civil rights limelight in 1951 by organizing the Regional Council of Negro Leadership, which championed self-help, entrepreneurship, thrift, and equal political rights. Assisted by his protégé, future civil rights icon Medgar Evers, he organized a successful boycott of service stations that denied restrooms to blacks. The council distributed 50,000 bumper stickers bearing the slogan, “Don’t Buy Gas Where You Can’t Use the Restroom.” It also staged mass rallies which sometimes drew 10,000 people or more.

While the council relied on peaceful methods, many members carried guns “just in case.” According to Simeon Booker, a correspondent with Jet magazine, Howard’s “security program was a model of dispatch and efficiency.” Mississippi’s activists generally operated under the theory that the best way to deter attacks by white supremacists was to appear capable of responding with deadly force. Also, any would-be shooter would find it difficult to get in close enough at a civil rights rally to make a successful kill, much less escape.

Armed self-defense became particularly important in 1955, after two white brothers in Mississippi murdered fourteen-year-old Emmett Till for allegedly whistling at one of their wives. During the trial of Till’s killers, Howard was relentless in digging up evidence. His home took on the character of a “black command center” for witnesses, journalists, and prominent visitors, including Emmett Till’s mother, Mamie Bradley, who stayed there during the ordeal. Firearms were ubiquitous. One visitor spied a magnum pistol and a .45 at the head of Howard’s bed, and a Thompson submachine gun at the foot. (The Justice Department is now reinvestigating Till’s slaying.)

Discriminatory gun control laws in Mississippi, and throughout the South, presented a major obstacle to civil rights activists. Sheriffs routinely denied concealed carry permits to African Americans. Howard evaded this rule by stowing his gun in a hidden compartment in his car just in case the police pulled him over. Years later, the Pittsburgh Courier reported that when he “rode the highways, he would take the gun from its secret hiding place and put it in his lap...always cocked!”

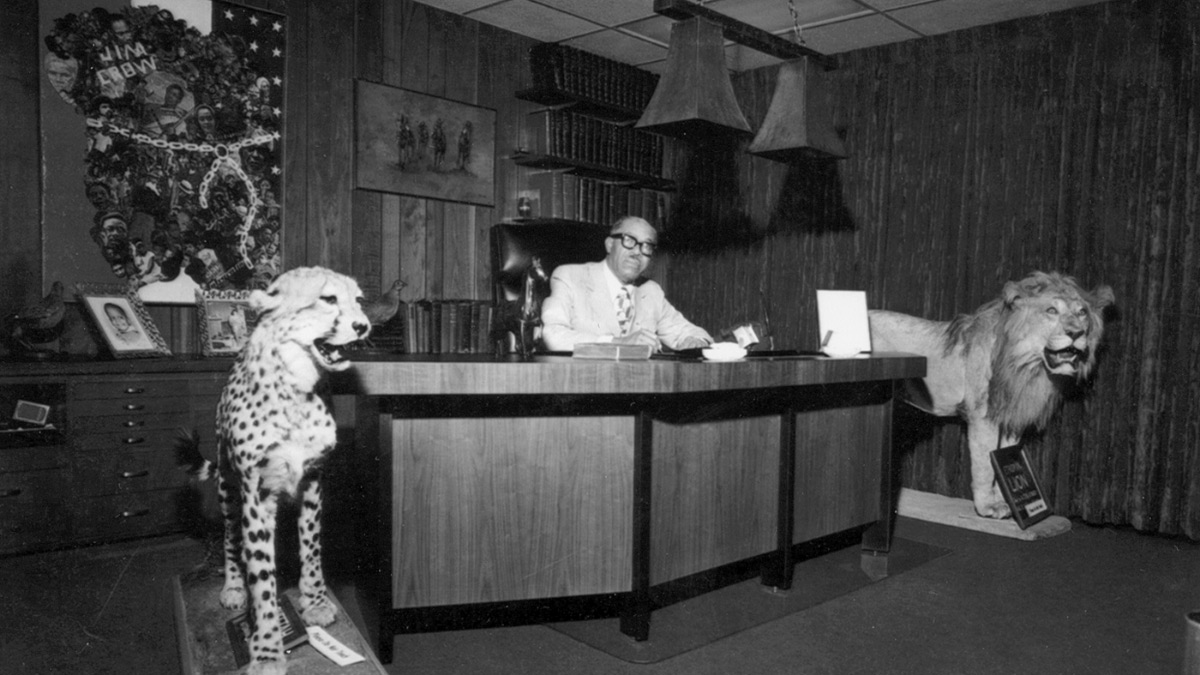

In 1956, after a policeman had beaten his wife Helen, Howard moved the family to Chicago, where he established a thriving medical practice. Although he no longer lived in constant fear, Howard did not retire his guns. In the public mind, he became increasingly identified with his favorite past-time of big-game hunting, and he decorated his mansion with impressive trophies he bagged during safaris in Africa.

Guns were not unique to Howard’s circle. During the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Rosa Parks and her husband slept with firearms at the ready. To justify guns for protection, Ella Baker of the Southern Non-Violent Coordinating Committee invoked the Second Amendment, as did Malcolm X. The Deacons for the Defense provided armed protection for Martin Luther King’s rallies.

Few activists, however, better exemplified the strategy of integrating guns with civil rights than T.R.M. Howard.