I was recently struck by the explosion of the federal government’s size and reach, as well as its apparent ambition to super-size itself even more, in an unusual way.

I had been looking up something in one of my old public finance textbooks, when I came across a section on the size and growth of government. What struck me was that the authors used exclamation points (an almost extinct species in such writing) over two decades ago to describe government’s expansion, particularly at the federal level. But the rate at which government has recently metastasized leaves those exclamation points in the dust. We would also have to use all caps today (as in “YOU MAY ALREADY HAVE WON”). From said book: total expenditures by all levels of government in 1990 were substantially smaller than just one of the recent stimulus bills.

That explosion of the federal government’s grasp, and the extent to which its attempted reach exceeds its grasp, has made limits on federal power once again among the most central political issues. Unfortunately, ignorance of our Founding severely impoverishes that discussion.

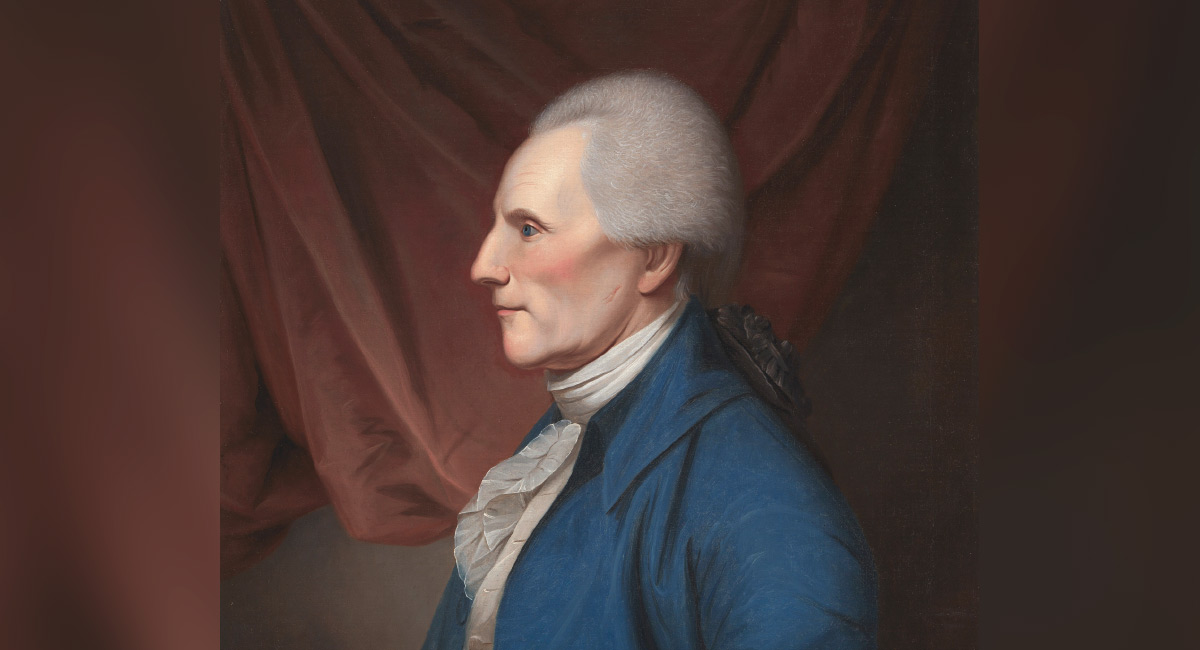

A good example comes from Richard Henry Lee, born January 20, 1732. Lee put forth the motion calling for the colonies’ independence. He was a leader in the Continental Congresses. He was elected Senator from Virginia, even though he opposed the Constitution’s ratification for lacking “a better bill of rights.”

But particularly important to America’s creation were Lee’s essays under the pseudonym, The Federal Farmer. His Letters from the Federal Farmer, which were both widely published in newspapers and sold thousands of copies as a pamphlet, provided impetus to the Bill of Rights, and his words deserve remembering:

We must have our rights maintained

A free and enlightened people...will not resign all their rights to those who govern...they will fix limits to their legislators and rulers...[who] will know they cannot be passed.

[Hope] cannot justify the impropriety of giving powers, the exercise of which prudent men will not attempt, and imprudent men will...exercise only in a manner destructive of free government.

National laws ought to yield to inalienable or fundamental rights—and ...should extend only to a few national objects.

It must never be forgotten...that the liberties of the people are not so safe under the gracious manner of government as by the limitation of power.

Our rights must be equal

I can consent to no government, which...is not calculated equally to preserve the rights of all orders of men.

We ought not...commit the many to the mercy, prudence, and moderation of the few.

In free governments, the people...follow their own private pursuits, and enjoy the fruits of their labor with very small deductions for the public use.

The people have a right to hold and enjoy their property according to known standing laws, and which cannot be taken from them without their consent.

Every government is a threat to our rights

We cannot form a general government in which all power can be safely lodged.

“Should the general government...[employ] a system of influence, the government will take every occasion to multiply laws...props for its own support.

Vast powers of laying and collecting internal taxes in a government ...would be...abused by imprudent and designing men.

Men who govern will...construe laws and constitutions most favorably for increasing their own powers.

Our countrymen are entitled... to a government of laws and not of men... if the constitution...be vague and unguarded, then we depend wholly on the prudence, wisdom and moderation of those who manage the affairs of government...uncertain and precarious.

Liberty, in its genuine sense, is security to enjoy the effects of our honest industry and labors, in a free and mild government.

How can we protect ourselves from government abuse?

All wise and prudent people...have drawn the line, and carefully described the powers parted with and the powers reserved...what rights are established as fundamental, and must not be infringed upon.

The powers delegated to the government must be precisely defined... that, by no reasonable construction, they can be made to invade the rights and prerogatives intended to be left in the people.

We must consider this constitution, when adopted, as the supreme act of the people...we and our posterity must strictly adhere to the letter and spirit of it, and in no instance depart from them.

Why...unnecessarily leave a door open to improper regulations?

The first maxim of a man who loves liberty should be never to grant to rulers an atom of power that is not most clearly and indispensably necessary for the safety and well-being of society.

Our true object is...to render force as little necessary as possible.

Historian Forrest McDonald described Richard Henry Lee as committed to the belief that “men are born with certain rights, whether they are honored in a particular society or not,” and the result was that he was “imbued with an abiding love of liberty and a concomitant wholesome distrust of government.” And he made that plain to anyone who was willing to hear, as when he said “To say that a bad government must be established for fear of anarchy is really saying that we should kill ourselves for fear of dying.”

His generation had learned of the need to keep government within narrow limits, as there are very few areas in which it can advance our general welfare, as opposed to some Americans’ welfare at other Americans’ expense. At a time when those limits have been eroded to the point that people can wonder if there are any surviving limits in many areas, we could benefit by relearning the wisdom Lee helped pass on nearly three centuries ago.