Speech given at "AdamSmith.Com: Free Enterprise and the New Economy"

A Conference Sponsored by the Intercollegiate Studies Institute at the Berkeley Marina Radisson Hotel in Berkeley, California

October 21, 2000

Dr. Alexander Tabarrok

Research Director, The Independent Institute

Good morning. It’s a pleasure to be talking about the new economy here in Northern California, the epicenter of the new economy. It’s amazing to remember that the World Wide Web was only invented in 1990 and the first Web browser in 1993. Since that time the number of Internet users has climbed from 12 to more than 350 million. Four years from now Internet use will reach one billion individuals. Just as the steam engine launched the industrial revolution, the railway dominated the economy of the late 19th century and electrification dominated the first half of the twentieth century, so computers and the Internet will dominate the next several decades.

The Internet, however, is only one part of a broader change in the economy which has been proceeding slowly for many years, that is the shift from production of physical goods to the production and application of ideas. The core industries of the new economy, microchips, software and telecommunications, as well as the products of leading sectors like health care, entertainment, and pharmaceuticals, are all based on ideas. What makes a microchip valuable is not the silicon which makes up the chip but the chip design. What makes a pharmaceutical valuable is not the chemicals which make up the pill but the way the chemicals are designed. Software is nothing but ideas laid out in a logical design.

What distinguishes the new economy from the old is not new technology per se but rather the greater importance of ideas - the economics of ideas calls for new policy. I summarize the most important in the following Five Lessons for the new economy.

1) In Leading Sectors of the New Economy, Monopoly is the Engine of Innovation.

Corollary 1a) Selling the same good to different consumers at different prices is not necessarily anti-consumer.

2) Market Share is Not a Good Indicator of Anti-Consumer Monopoly Power.

3) Free Trade is More Important than Ever.

4) The Digital Divide is about the Failure of Government Schools not the Failure of the New Economy.

5) Venture Capital Beats Industrial Policy Any Day.

In leading sectors of the new economy, monopoly is the engine of innovation. Idea-based goods typically have high design costs and low production costs. It cost about $500 million dollars to create the first pill of a new drug like Viagra, but the second pill costs only pennies to produce. The economics of high design costs and low production cost imply that monopoly power can be desirable. Pfizer has a monopoly on the production of Viagra. If any firm were allowed to copy Viagra, competition would drive prices down to production cost. But if the price falls to production cost, then design costs cannot be recouped and no incentive remains to make the investments in research and development which are necessary to create a drug like Viagra in the first place. If Pfizer didn’t have a monopoly on Viagra, Viagra would never have been created. Thus, another way of stating the first lesson of the new economy is that not all monopolies are to be avoided.

Now in some sectors of the economy this has been explicitly recognized. We grant patents, which are a legally enforced monopoly rights, to pharmaceutical manufacturers. We give copyrights to producers of books and musical performances although we are now debating about what to do when copyright becomes easy to surmount as with peer-to-peer distribution software such as Napster and Gnutella.

In other areas, particularly in antitrust policy, however, government has not understood the first lesson of the new economy. The antitrust attack on Microsoft, is a one example. Another is the investigation of eBay, both of which I will discuss at greater length shortly.

Before turning to that, however, I want to examine a corollary of the first lesson: Selling the same good to different consumers at different prices is not necessarily anti-consumer. The ethics and economics of selling the same good for different prices to different consumers is currently a big issue in the Presidential campaign with respect to pharmaceutical prices.

Vice-President Gore and others have attacked the pharmaceutical companies for selling drugs at higher prices in America than in developing countries like Mexico or India. Gore also famously claimed that the same drug cost less for his dog than his mother. In either case, the fact that some consumers get lower prices than others is supposed to show that the consumers being charged the higher prices are being ripped off and exploited and that the pharmaceutical firms are earning obscene profits.

Now, it is true that drugs are cheaper in less-developed countries than in the United States, but this is a benefit not a cost to US consumers. Charging a lower price in less-developed lets poor people buy some drugs which they otherwise could not afford and the extra revenues from these consumers help to cover some of the design costs, US consumers are better off than they would be if firms charged the same prices everywhere.

Put simply, if firms had to charge a single low price throughout the world there would be much less money to spend on R&D and fewer new drugs. If firms had to charge a single high price throughout the world, consumers in less developed countries could not afford to buy any new drugs, and US consumers would pay all of the R&D costs. Allowing a firm to charge different prices in different parts of the world - benefits consumers everywhere. (The same principle explains why Gore’s mother should not be upset that her son’s dog gets a lower priced prescription than she does - if pharmaceutical firms were forced to charge one price to all consumers then the price for the dog would rise and the total funds available for R&D would fall.)

It is true that some countries free ride on the US market by forcing pharmaceutical firms to sell drugs at below market prices and by expropriating their intellectual property. In the US, the state of Maine has passed a bill to control pharmaceutical prices and Vice President Gore has signaled that he might support similar national legislation. Price controls would be a disaster for US consumers and indeed for all health consumers worldwide. As Ronald Reagan once said when arguing about tariffs, if you are in a boat with another guy and he shoots a hole in the floor - it doesn’t make sense to retaliate by shooting a second hole. Instead of sinking the boat, we must press for full protection of intellectual property rights around the globe - in this way spreading the costs of R&D as wide as possible and therefore pushing the prices of drugs down as low as possible.

The second lesson for the new economy is that Market Share is Not a Good Indicator of Anti-Consumer Monopoly Power. This has always been the case although the principle is especially true in markets which exhibit what economists call "network value." Let me explain.

In many areas of the new economy the value of a product to you depends on how many other people use that product. The telephone is an old example of this principle. The first telephone or the first FAX machine is useless. Two telephones have some uses but the value of a telephone increases the more telephones there are. eBay provides an example of this process in the new economy. Buyers flock to eBay because that is where the most sellers are and thus where they are most likely to find the product they are looking for. Sellers flock to eBay because this is where the most buyers are. The fact that eBay is big, therefore, gives it an advantage over its rivals in staying big. Consumers will continue to use eBay even if it is more expensive than its rivals. As proof, note that Yahoo offers free auctions but as of yet Yahoo is much smaller than eBay. Now one response to this is to say that eBay has monopoly power, that customers are locked in to eBay and thus exploited. But this is wrong on at least two counts.

First, it is difficult to claim that consumers are exploited when eBay offers a great service at a low price. It’s typically cheaper to advertise something on eBay than it is to buy an ad in a local newspaper, and eBay reaches far more customers than any newspaper in the world.

Second and more importantly, eBay does face competition but it is competition for the market rather than competition in the market. In the new economy firms compete to be "king of the hill." The economics of network value insure that one firm will dominate the market – but the economics don’t say which firm will dominate, and so there is periodically a battle royale in which one firm completely displaces another firm. In the word processor market, for example, WordStar had an overwhelming market share until it was driven into oblivion by WordPerfect which in turn dominated the market for several years until it was driven off the top of the hill by Microsoft Word.

Staying at the top of the hill is very difficult in the new economy because competition for the market is intense. This is one reason why shares in high-technology companies are so volatile. When you are king of the hill, everything is golden, but when a competitor threatens to push you off, you can go from a 90% market share to a 10% market share in a matter of years.

As I already noted, Yahoo sells auction services for free. Thus eBay must keep its prices low and it must continue to innovate, for example, with auction insurance (which eBay offers but Yahoo does not), if it wants to maintain its market share. Consumers benefit enormously, of course, from the competition between eBay, Yahoo and other firms each vying to be the King of the Hill.

Consumers have also benefited enormously from Microsoft’s efforts to displace Netscape and other firms as King of the Hill. When Netscape was selling its browser for $40, Microsoft started giving IE away for free. Just like Yahoo in the auction market, MS saw that hundreds of millions and potentially billions of customers were available to whichever firm became King of the Browser Hill - thus they competed aggressively with Netscape. They did not get very far, however, until the quality of IE improved so much that computer magazines began saying that IE was of equal and perhaps better quality than Netscape Navigator.

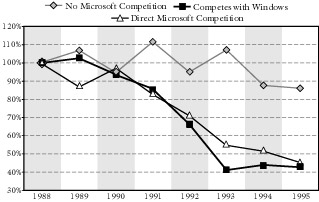

Microsoft’s action in this and in other markets such as for Word Processors and Spreadsheets dramatically lowered prices to consumers.

This Figure from Stan Liebowitz’s and Stephen Margolis’s excellent book Winners, Losers & Microsoft shows what happened to prices in markets in which Microsoft competed directly or competed through the operating system (things like disk compression) as compared to prices in markets that MS did not compete in. As you can see from the figure, prices in markets that MS competed in fell by an average of 60% over the 7 years from 1988 to 1995, while prices in markets in which MS did not compete fell by only 15%. Nor has MS raised prices once it has come to dominate a market. Indeed, this would not make good business sense since MS too will be pushed from the top of the hill when it fails to produce better products at lower prices. On the one hand, it seems ridiculous to say that Linux could be a competitive threaten to Windows - in the old economy this would be something like saying that U.S. Electric Car Inc, a small firm specializing in electric cars, threatens General Motors. Yet, in the new economy the threat is real. We have seen time and time again how a small firm comes out of now-where to claim an entire market. Atari did that in 1977 when it released Pong and became the fastest growing firm in all of history, but it lost out to Sega and Nintendo which are know being wiped out by Sony. By 1986, less than 10 years after the launch of the Atari 2600, Atari was a very minor player in the industry that it had begun and dominated just a few years before. VisiCalc was the first popular computer spreadsheet but it lost its 90% plus market share to Lotus which has lost out to Excel. Who knows what is next? Maybe Windows or its progeny will be the dominant operating system 10 years from now. But nobody knows - suppose that tomorrow an upstart firm announced that it had created a new operating system with built-in improved voice-recognition capacity? It doesn’t strain belief to think that MS could lose its dominance just as many other firms in the new economy have before.

Thus, to recap the lesson. A large market share does not imply anti-consumer monopoly power. This is a lesson which the antitrust authorities have not learned. (Best book on topic is Liebowitz and Margolis, Winners, Losers, and Microsoft).

The third lesson is that Free Trade is more important than ever. As Thomas Jefferson pointed out, one of the interesting things about ideas is that "He who receives an idea from me, receives instruction himself without lessening mine; as he who lights his taper at mine, receives light without darkening me." Since the design costs of a drug or computer chip or piece of software are the same regardless of whether ten thousand or ten million consumers purchase the good - the greater the size of the market, the lower the per unit cost of the good. In conventional markets we think of an increase in demand as increasing prices but increasing returns to scale and network value mean that in the new economy an increase in demand lowers prices because it allows design costs to be spread more widely. Globalization and the new economy thus complement one another.

Moreover, the larger the potential market that a firm in the new economy faces, the greater the incentive to invest in research and development. There are many new chip designs and drugs that are worth investigating and researching if the potential market is the world - which are not worth investing in if the potential market is limited to the United States. Similarly the value of networks increases with size. eBay, Windows, Excel, standards for movies and music such MP3, JPEG , etc. are even more useful if they can operate on a worldwide scale.

The fourth lesson is that The digital divide is about the failure of government schools not the failure of high-tech business.

There is a lot of nonsense coming from the Clinton administration about the so-called digital divide, the difference in adoption rates of Internet technology by blacks versus whites, and poor versus rich. Internet adoption is probably the fastest adoption of any new technology that has ever occurred - faster even than television. The price of computers and Internet connections is dropping so rapidly that today you can get a decent computer for almost free bundled with a $22 per month Internet connection. A mere seven years after the first browser was created, more than 15 percent of homes with an income of less than 5,000 dollars a year have an Internet connection and 95 percent of all public schools are connected! Yet President Clinton calls this a crisis and a threat to the nation’s future!

Perhaps the most deceptive claim is that the digital divide is growing. Of course it is growing. A few years ago no one had Internet access - so there was no digital divide and we were all equal. Today many people, rich and poor, have Internet access but more of the rich than the poor have access - who would expect otherwise? It is utterly common that a new technology starts out expensive and falls in price over time and thus is adopted first by the rich and only later by the poor. Americans saw the same thing with television, the VCR, the CD player and now with Internet access - today 97.9 percent of all households have color televisions, and 90 percent have a VCR (some of the remaining ten percent have DVDs instead!).

It is to be expected, therefore, that after widening for a time the digital divide will decrease until computers and Internet access become widespread among the poor as well as the rich. Computers and Internet access, however, are unlikely to become as widespread as televisions and VCRs.

Here is where we get to the kernel of truth in the digital divide. Because computers and the Internet have greater value to the more educated we can expect that some of the digital divide will remain no matter how far the price of a computer falls. By its nature, the new Internet technologies appeal to those who greatly value access to information. Certainly the Internet is democratizing information - just as did the 19th century library movement. Nevertheless, someone who does not (and perhaps cannot) read the newspaper or who never has had use for an encyclopedia is unlikely to be impressed with online newspapers and encyclopedias.

The racial aspect of the digital divide follows directly from the fact that 26 percent of African-Americans do not finish high school. The contrast between government and private enterprise here is stunning. In less than 10 years private enterprise has wired up hundreds of millions of people and opened up fantastic new educational opportunities for everyone. By contrast, government run schools have failed to maintain standards let alone open up new educational opportunities.

Sadly, government has failed the poor and minorities most of all. Many of the schools in America’s inner-cities operate in dilapidated buildings with unqualified teachers and out-of-date textbooks. As a result, the students of these schools are utterly unprepared to succeed. Many of them cannot read or do simply arithmetic let alone prosper and advance in today’s high-tech job market.

If we want to bridge the digital divide, we must begin by teaching all students how to read, write and do arithmetic. Nineteenth century skills must precede twenty-first century skills. The government schools have failed to teach these skills.

Ironically, California leads the world in the digital revolution but its schools are among the worst in a nation whose schools are among the worst in the developed world. The true digital divide is the divide between California’s high-tech economy and it’s antiquated school system.

Given the failure of the government schools, it is time to harness the same forces which have given us the digital revolution to the goal of educating children. Proposition 38, which would expand the field for private schools in California, is an excellent idea. It’s no accident that the proposition is being supported by Tim Draper who made his money as a venture-capitalist in high-tech. Draper surely understands the disconnect between California’s amazing high-tech sector and it’s moribund education system.

Lesson five is that Venture Capital Beats Industrial Policy Any Day. It’s useful to begin with a little recent history. In the late 1980’s and early 1990’s the intellectual classes in America were swept up by Japan phobia. The non-fiction bestseller list was dominated by books like Clyde Prestowitz’s Trading Places: How We Are Giving Our Future to Japan and How to Reclaim it, Robert Kearns Zaibatsu America: How Japanese Firms are Colonizing Vital U.S. Industries, Chalmers Johnson’s MITI and the Japanese Miracle and Michael Crichton’s popular anti-Japan novel Rising Sun. In the late 1980’s and early 1990’s you could hear the authors of these books and their followers everywhere, they were featured on all the hot talk shows and could be found at all the prestigious government hearings.

These revisionists argued that Japan had already overtaken the US in most areas and was destined to soon rule the world. Prestowitz (1988, 94) for example, wrote that

"In 1981, the United States, although less dominant than previously, was still the world leader in industry, technology, and finance as well as in military power. In 1987, it was the leader only in military power, and even there was facing the necessity of reducing commitments. In other areas, the United States...had traded places with its former protégé - Japan."

In Prestowitz’s words the US was "a colony in the making."

The reality, of course, has been far different from the predictions of the revisionists. The Japanese economy has been mired in a slump for almost ten years, the Japanese stock market is 60% below its 1989 high, real estate values have crashed, banks in Japan are in crisis, unemployment is at for Japan historical high levels. Most clearly, the US economy is very obviously the world leader in industry, technology and finance.

The point, however, is not to be triumphalist. The revisionists were wrong about just about everything - including the idea that Japan and the US were involved in some sort of economic war. Japan’s success did not come at America’s expense and Japan’s current economic downturn is detrimental, not helpful, to America.

I want to focus on one mistake of the revisionists in particular because it was perhaps the biggest. The revisionists argued that the problem with America was laissez-faire economics. Chalmers Johnson went so far as to say that "If the United States were a well run country, neoclassical economists would be hanging from the Capitol dome." (Somehow, I don’t think he was talking about putting up pictures of Milton Friedman.)

In contrast to America’s laissez-faire economics, the revisionists extolled "industrial policy," the government as market guide. According to the revisionists, Japan succeed precisely because it operated like a giant unified body or corporation, Japan Inc. with MITI, the Ministry for International Trade and Industry, as the body’s brain. MITI, according to the revisionists, set the goals for the Japanese economy. It identified which technologies were the key to the future and it organized Japanese corporations to go after these goals. In sector after sector, therefore, the Japanese economy was said to be leaping ahead of its American rival.

As it turns out, all of this was quite wrong. The revisionists exaggerated the importance of MITI and moreover MITI was never able to predict winners and losers - MITI tried to stop Sony, for example, because it felt that consumer electronics were not a strategic industry. Overall, MITI almost certainly did more harm to the Japanese economy than good.

We can perhaps best see the error of industrial policy by noting that the singular fact of the new economy is that it was not planned, it was not the result of a five-year plan. The Internet was created bottom up, not top down, and neither MITI nor DARPA nor any other government agency foresaw the Internet and the immense changes that it would be bring. Indeed, had we lived in society where technological change is planned from the top down it is clear that the Internet would never have happened because hardly anyone saw the importance of the Internet before it was upon us. Only a handful of entrepreneurs had any inkling about what the Internet might mean. Jim Clark and Marc Andreesen understood, Jeff Bezos understood and Steve Case understood, and not many others. The key fact, however, is that these entrepreneurs were able to convince venture capitalists that the vision was worth investing millions in. Part of what made this process work was that the venture capitalists knew that if they bet right government for the most part would not stand in their way, their profits would not all be sucked up by the IRS, and the firms they threatened, the old guard, would probably not be able to suppress them through government regulation.

It’s important to remember that Bill Gates, one of the smartest businessmen of his time, did not see the importance of the Internet until it was almost too late. The fact that Bill Gates missed the Internet tells us that even if we made Bill Gates the head of an American MITI, government industrial policy would still not be a good idea. We humans tend to be too anthropocentric - when we see the success of a Gates, Clark, or Bezos we tend to think that their success was purely personal and can be duplicated in other areas - Perot for President! Without in any way detracting from the talents of Gates, Clark, Bezos or Perot, all of whom I admire, I would say that if we want to explain why the American economy has done well in the last ten years, we should focus our attention not on Gates, Clark, Bezos et al. but on the openness of American markets that has enabled then unknown people with strange ideas to attract millions of dollars of capital, start new businesses.

The success of American markets, and with this I will conclude and open up for questions, is not Bill Gates but the fact that at any moment the next Bill Gates could come from anywhere. It’s the fact that a 19 year old student like Shawn Fanning can write a software program, find millions of dollars in venture capital funding, open offices, and start a music revolution all within the space of a year.

Thank you.