There are not very many good things you can say about a deep recession. But from a researcher’s point of view, there is one silver lining. This recession has given us a natural experiment in health economics—and the results are stunning.

But, first things first. Here is the conventional wisdom in health policy:

- In the United States, we ration health care by price, whereas other developed countries rely on waiting and other non-price rationing mechanisms.

- The U.S. method is especially unfair to low-income families, who lack the ability to pay for the care they need.

- Because of this unfairness, there is vast inequality of access to care in the U.S.

- ObamaCare will be a boon to low-income families—especially the uninsured—because it will lower price barriers to care.

As it turns out, the conventional wisdom is completely wrong. Here is the alternative vision, loyal readers have consistently found at this blog:

- The major barrier to care for low-income families is the same in the U.S. as it is throughout the developed world: the time price of care and other non-price rationing mechanisms are far more important than the money price of care.

- The U.S. system is actually more egalitarian than the systems of many other developed countries, with the uninsured in the U.S., for example, getting more preventive care than the insured in Canada.

- The burdens of non-price rationing rise as income falls, with the lowest-income families facing the longest waiting times and the largest bureaucratic obstacles to care.

- ObamaCare, by lowering the money price of care for almost everybody while doing nothing to change supply, will intensify non-price rationing and may actually make access to care more difficult for those with the least financial resources.

Interestingly, the natural experiment that forms a test for these two visions is the recession.

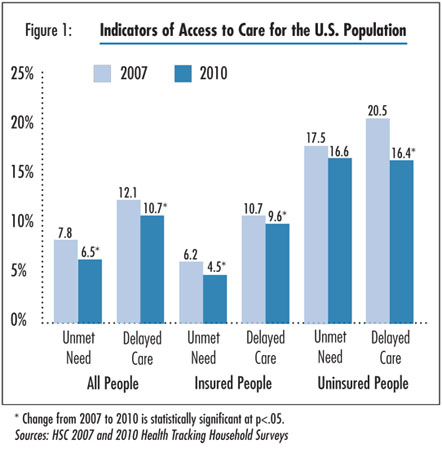

As explained in a recent report from the Center for Studying Health System Change, middle class families are responding to bad economic times by cutting back on their consumption of health care. They are postponing elective surgery, forgoing care of marginal value, and making more cost-conscious choices when they do get care. This reduction in demand is freeing up resources which are apparently being redirected to meet the needs of people who face price and non-price barriers to care. From 2007 to 2010:

- The percent of the population experiencing an unmet health care need actually fell from 7.8% to 6.5%.

- The percent of people who say they have delayed care fell from 12.1% to 10.7% over the same period.

And this is in the middle of one of our worst recessions!

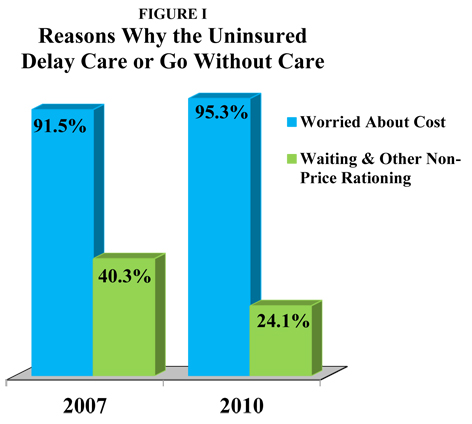

As Figure I shows, during the recession the money price barrier to care actually rose among the uninsured, although the increase was not statistically significant. The number of uninsured people reporting access problems because they were “worried about cost” rose from 91.5% to 95.3%. (Translation: virtually everybody who is uninsured worries about cost.) Yet over the same period, the number of people experiencing access problems because of waiting and other non-price barriers was almost cut in half (falling from 40.3% to 24.1%).

Source: Center for Studying Health System Change

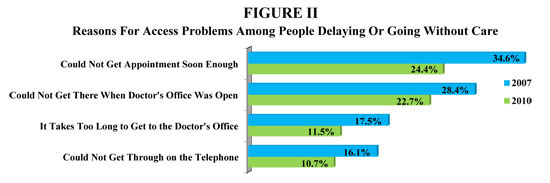

Clearly, the decrease in non-price barriers is what is responsible for the dramatic increase in access to care. Figure II shows what some of the most important of these changes were.

Source: Center for Studying Health System Change

These results are consistent with an earlier study we reported on. When North Carolina Medicaid tripled both the time price of obtaining prescription drugs and the money price, researchers found that time was more important than money in deterring access to care.

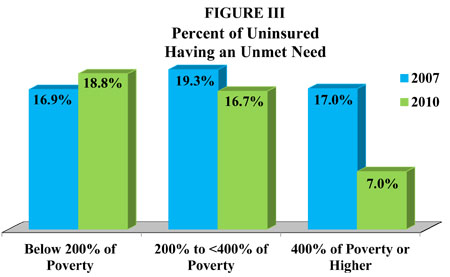

Figure III is I think the most important figure of all. Suppose that in an attempt to increase access to care, we add one more doctor, one more nurse or one more clinic. Who is likely to benefit? The figure implies that the higher your income, the greater the likelihood you will gain. During the recession, for example, the percent of people experiencing an unmet need with income at 400% of the poverty level or above was more than cut in half. Yet, among those with income below 200% of poverty, the percent of those with unmet needs actually rose.

Source: Center for Studying Health System Change

Think (metaphorically) of a waiting line for care. The lowest-income families are at the end of that line. The longer the line, the longer they will have to wait for care. If you do something to shorten the line, you will be mainly benefitting higher-income people who are at the front of the line.

Why is that? As I have explained before, many of the skills that allow people to do well in the market are the same skills that allow them to do well in non-market settings. High-income, highly educated people, for example, will find a way to get to the head of the waiting line, whether the thing being rationed is quality education, health care or any other good or service. Low-income, poorly educated individuals will generally be at the rear of those lines.

One policy implication is that we should allow low-income people on Medicaid greater access to services whose prices are determined in the marketplace. For example, let Medicaid enrollees add to Medicaid’s fee with out of pocket money and pay the market price at walk-in clinics, surgi-centers and free standing emergency care clinics. Another implication is that we should make it easier for market-based suppliers of care to reach low-income patients (e.g., by relaxing occupational licensing restrictions).

A third implication concerns ObamaCare. As we have pointed out before, about 32 million people are expected to be newly insured, and if economic studies are correct, they will try to double their consumption of medical care. The act inexplicably forces middle- and upper-middle income families to have more coverage than they would have preferred (a long list of preventive services with no deductible or copayment); and once they have it they will use it. Yet in the light of this rather large increase in demand, nothing in the act really increases supply. (I suspect this was to induce the bean counters at CBO to low-ball their estimate of the cost of the bill—if there are no new doctors, CBO is likely to assume there will be no additional care, regardless of what was promised.)

What we can expect is a rather large increase in non-price rationing—as waiting lines grow at the family doctor’s office, the emergency room and everywhere else. In such an environment it is inevitable that those people in a health plan that pays fees below the market price will be pushed to the end of the waiting lines. These include the elderly and the disabled on Medicare, low-income families on Medicaid and (if Massachusetts is a guide) people with subsidized insurance in the newly created health insurance exchanges.

Ironically, ObamaCare may end up hurting the very people many ObamaCare supporters thought they were going to help.