Critics of Microsoft, rallied by Judge Thomas Penfield Jackson’s finding that the company has monopoly power over much of the computer industry, have urged a breakup of the company. For example, the Consumer Project on Technology (affiliated with Ralph Nader) suggests that Microsoft be forced to divest its Web browser, Internet Explorer. But other far more radical divestiture proposals are under consideration. The 19 state attorneys general who were co-plaintiffs in the antitrust suit are said to be pressing for a horizontal breakup that would divide Microsoft into three companies: one with the operating system, one with applications software, and one with Internet businesses. Still other critics have called for a vertical divestiture that would divide Microsoft into three or more fully integrated companies (“Baby Bills”) that would then, presumably, compete with one another in the marketplace.

Even friends of liberty have suggested that some sort of divestiture might make economic sense. Peter Huber, in an important article in the Wall Street Journal (“Breaking Up Isn’t Hard to Do,” November 10, 1999) argued that it could be good for Bill Gates and for Microsoft’s investors since “the children of broken up corporate marriages tend to fare remarkably well.” He cites Standard Oil, Alcoa, and AT&T, all of which prospered after the government broke up the parent companies.

Yet it strains belief to imagine that the trust-busters or courts know how to maximize shareholder return better than private entrepreneurs. If divestiture were better for John D. Rockefeller or Bill Gates, they could always have spun off their own companies. When firms are worth more apart than together, they are broken up by management or, when management is oblivious to market realities, by outsiders in hostile takeovers, such as occurred with many large conglomerates in the 1980s.

Contrary to Huber and others, government divestiture is no panacea. Standard Oil, American Tobacco, Alcoa, United Shoe Machinery, and AT&T were all broken up with mixed results for the companies and consumers. Standard Oil did well after the 1911 breakup because it was still the largest integrated domestic refiner. American Tobacco prospered because divestiture did not affect the success of its popular brand names. Alcoa survived its split from Alcan in 1951 because the breakup had no significant effect on domestic aluminum production or sale. However, United Shoe Machinery declined rapidly after divestiture in 1968, and the AT&T situation is clouded because radical telecommunications deregulation—and not the antitrust breakup per se—was responsible for the explosion in post-divestiture revenues.

Effect on Consumers

The effects of divestiture on consumers are even more problematic. In petroleum, for example, refined oil prices fell for decades prior to divestiture; in the decade after the breakup—and even before World War I—prices increased sharply and stabilized. Alcoa had a near "monopoly" in virgin ingot aluminum for almost 50 years, and prices declined from $5 per ingot pound in 1887 to 22 cents in 1937, when the monopoly trial began; after the decision against Alcoa in 1945 and after the divestiture of Alcan, prices increased and stabilized.

Subsequent to the oil and aluminum breakups, dominant firm market shares declined somewhat and smaller competitors expanded their business. But this development was not necessarily efficient or pro-consumer. More likely, the breakups prevented the exploitation of the efficiencies from integration (especially in the oil industry), causing increases in costs and prices that allowed less efficient competitors to expand production and sales. In aluminum, the court-ordered restraints on the purchase of World War II aluminum facilities, plus the compulsory licensing of patents to rivals, made Alcoa a less efficient supplier. In both cases particular competitors, but not necessarily consumers, benefited from antitrust regulation.

The closest case to Microsoft is the 1968 breakup of United Shoe Machinery, which was blatantly anti- consumer and anti-investor. Like Microsoft, United Shoe was an aggressively competitive dominant firm that maintained its market position through massive investments in shoe machine technology and low prices. And like Microsoft, it often bundled the lease of its machines with certain services. The trial judge in the case actually praised United’s overall economic efficiency.

But as in the Microsoft case, smaller rivals found it difficult to compete with United’s superior line of machines and favorable long-term leases. That difficulty—and not any concern with consumer welfare or efficiency—was the judge’s determining consideration. He shortened the leasing contract arbitrarily and ended the bundling in order to help smaller competitors. In 1968, at the insistence of the Department of Justice, the Supreme Court went further and ordered United Shoe to spin off significant shoe machine assets, subsidize a new “competitor,” and refrain from active competition with the newcomer for up to five years. This regulatory attempt to “create competition” proved disastrous: United Shoe Machinery, and the domestic shoe industry that it served, both declined steadily after divestiture. Now most shoes are made overseas.

Standard Oil, Alcoa, United Shoe Machinery—and especially Microsoft—all earned their initial market positions by being more efficient than their rivals. Any regulation or devolution of a successful corporate organization is likely to reduce efficiency and consumer welfare. Antitrust history is littered with attacks on successful companies and with regulatory attempts to redistribute the spoils of success to less efficient rivals. Such antitrust protectionism is both immoral and destructive of productivity and wealth.

Judge Jackson, having already decided incorrectly that Microsoft is a monopoly that restrains trade, ought not to compound his errors of “fact” by ordering some punitive and socially harmful industrial reorganization.

The Microsoft Case: Divestiture Won’t Help Consumers

Also published in The Freeman

This article is reprinted with permission from The Freeman, April 2000. © Copyright 2000, the Foundation for Economic Education.

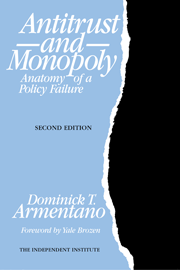

Dominick T. Armentano is a Research Fellow at the Independent Institute and professor emeritus in economics at the University of Hartford (CT).

Comments

Before posting, please read our Comment Policy.