U. S. House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform

aa

Subcommittee on Energy Policy, Health Care and Entitlements

Mr. Chairman and members of the Committee, thank you for the opportunity to testify on this important topic.... I welcome the opportunity to share my views and look forward to your questions.

The principle problems in health care are well known. The cost is too high; the quality is too low; and access to care is too difficult. The reason for these problems should also be well known: We have replaced the patients with third-party payers (insurance companies, employers, and government) as the principal buyers of care.

The party that pays for care is different from the party that is supposed to benefit. Unfortunately, the interests of the two parties are not always the same.

Lack of Transparency

One consequence of the third-party payer system is the complete suppression of normal market processes. In health care, few people ever see a real price for anything. Employees never see a premium reflecting the real cost of their health insurance. Patients almost never see a real price for their medical care. Even at the family doctor’s office, it’s hard to discover what anything costs. For something complicated, like a hip replacement, the information is virtually impossible to obtain—at least in advance of the operation.

Although many would like to think that our system is very different from the national health insurance schemes of other countries, the truth is that Americans mainly pay for care the same way people all over the developed world pay for care at the time they receive it—with time, not money.

On the average, every time we spend a dollar at a physician’s office, only 10 cents comes out of our own pockets. The rest is paid by third-party payers (insurance companies, employers, and government). As a result, for most people, the time price of care (waiting to get an appointment, getting to and from the doctor’s office, waiting in the reception area, waiting in the exam room, etc.) tends to be greater—and probably much greater—than the money price of care.

When patients aren’t spending their own money, doctors will not compete for their patronage based on price. When doctors don’t compete on price, they won’t compete on quality either. The services they offer will be only those services the third parties pay for and only in settings and ways the third parties have blessed.

Misconceptions about Transparency

In a very real sense, there are no prices at a typical physician’s office. Medicare pays one rate, Medicaid another, BlueCross yet a third. These payment rates are not real prices, however, and they do not play the same role as prices do in other markets. Yet, there is a tendency on both the political right and the political left to ignore this fact.

The right, for example, issues frequent calls to make prices transparent. A number of proposals would even require doctors and hospitals to post their prices. Yet, what possibly could be gained by posting these rates on the wall? If you are a BlueCross patient, how does knowing what an Aetna patient is paying help you in any way?

On the left, a common view is that health costs are too high because health care prices are too high. They believe that the way to control costs is to push prices down. This idea is actually written into the Affordable Care Act (ACA). All kinds of efficiency ideas are included in the ACA, but when all else fails—and most knowledgeable people believe that all else will fail—the ACA will try to solve the problem of rising Medicare costs by squeezing the providers. Medicare’s chief actuary predicts that by the end of the decade, Medicare fees for doctors and hospitals will be substantially lower than Medicaid’s and one in seven hospitals will leave the Medicare system.

The problem with this approach is that prices in health care are symptoms of problems, not causes of problems, in the same way that a high body temperature is a symptom of a fever. Just as it would make no sense to try to treat a fever by lowering the body’s temperature, it makes no sense to try to control prices while ignoring why they are what they are. Plus, when we treat symptoms rather than their causes, there are inevitably unanticipated negative consequences. For example, if we tried to impose low fees on every provider for all patients, we would begin to drive the most capable doctors out of the system—into alternative pay-cash-for-care services and perhaps even out of health care altogether.

But there is an even more fundamental problem with trying to solve the problem of cost by suppressing prices. The suppression of provider payments is an attempt to shift costs from patients and taxpayers to providers. Even if we get away with it, shifting costs is not the same thing as controlling costs. Doctors are just as much a part of society as patients. Shifting cost from one group to the other makes one group better off and the other worse off. It does not lower the cost of health care for society as a whole, however.

Competition in Health Markets without Third-Party Payers

In those health care markets where third-party payment is nonexistent or relatively unimportant, providers almost always compete for patients based on price. Where there is price competition, transparency is almost never a problem.

All over the country, retail establishments are offering primary care services to cash-paying patients. Because these services arose outside of the third-party payment system, their prices are free market prices. Walk-in clinics, doc-in-the-box clinics, and freestanding emergency care clinics post prices and usually deliver high quality care.

Cosmetic surgery is rarely covered by insurance. Because providers know their patients must pay out of pocket and are price-sensitive, patients can typically (1) find a package price in advance covering all services and facilities, (2) compare prices prior to surgery, and (3) pay a price that has been falling over time in real terms—despite a huge increase in volume and considerable technical innovation (which is blamed for increasing costs for every other type of surgery).

In the market for LASIK surgery, patients face package prices covering all aspects of the procedure. As with cosmetic surgery, whenever there is a price transparency and price competition, the cost tends to be controlled. From 1999 (when eye doctors began performing Lasik in volume) through 2011, the real price of conventional Lasik fell about one-fourth. There is also quality competition—patients can choose traditional LASIK or more advanced custom Wavefront LASIK. The cost of conventional Lasik was about $1,630 per eye in 2011, with most people opting for the more advanced Lasik surgery at an average cost of $2,150 per eye.

Even when providers do not explicitly advertise their quality standards, price competition tends to force product standardization. This reduced variance is often synonymous with quality improvement. Rx.com, for example, initiated the mail-order pharmacy business, competing on price with local pharmacies by creating a national market for drugs. Industry sources maintain that mail-order pharmacies have fewer dispensing errors than conventional pharmacies. Walk-in clinics, staffed by nurses following computerized protocols score better on quality metrics than traditional office-based doctor care and have a much lower variance.

In general, medical services for cash-paying patients have popped up in numerous market niches where third-party payment has left needs unmet. It is surprising how often providers of these services offer the very quality enhancements that critics complain are missing in traditional medical care. Electronic medical records and electronic prescribing, for example, are standard fare for walk-in clinics, concierge doctors, telephone, and email consultation services, and medical tourist facilities in other countries. Twenty-four/seven primary care is also a feature of concierge medicine and the various telephone and email consultation services.

Domestic Medical Tourism

In the international tourism market, where people travel for their care, quality is almost always a factor. Cost is also a factor because the patient is typically paying the entire bill out of pocket. Patients generally get package prices for most types of elective surgery and hospitals generally post their quality metrics online.

Is it possible to replicate this experience in the domestic hospital marketplace? Developments are under way. By one estimate 430,000 nonresidents a year enter the United States for medical care. Canadian patients seeking medical care at U.S. hospitals, for example, are able to get package prices that are about half of what BlueCross patients typically pay.

An essential ingredient in this market is the willingness to travel. If you ask a hospital in your neighborhood to give you a package price on a standard surgical procedure, you will probably be turned down. After the systematic suppression of normal market forces for the better part of a century, hospitals are rarely interested in competing on price for patients they are likely to get as customers anyway.

A traveling patient is a different matter. This is a customer the hospital is not going to get if it doesn’t compete. That’s why a growing number of U.S. hospitals are willing to give transparent, package prices to out-of-towners; and these prices often are close to the marginal cost of the care they deliver.

North American Surgery has negotiated deep discounts with about two dozen surgery centers, hospitals and clinics across the United States, mainly for Canadians who are unable to get timely care in their own country. The company’s cash price for a knee replacement in the United States is $16,000 to $19,000, depending on the facility a patient chooses, making it competitive with facilities in other countries.

But the service is not restricted to foreigners. The same economic principles that apply to the foreign patient who is willing to travel to the United States for surgery also apply to any patient who is willing to travel. That includes U.S. citizens. In other words, you don’t have to be a Canadian to take advantage of North American Surgery’s ability to obtain low-cost package prices. Everyone can do it.

The implications of all this are staggering. The United States is supposed to have the most expensive medical care found anywhere. Yet many U.S. hospitals are able to offer traveling patients package prices that are competitive with the prices charged by top-rated medical tourist facilities in such places as India, Thailand and Singapore.

All of this illustrates something many readers may already know. Markets in medical care can work and work well—especially when third-party payers are not involved.

Creating a Market for Medical Services

Two relatively new services are facilitating a market for medical services—with price and quality competition, as well as transparency. One is MediBid, which takes a Priceline approach to medical care. Another service, Healthcare Blue Book (HCBB), offers a free service for patients—showing the average price for various procedures in almost every zip code in the country. Moreover, both businesses have created new tools that are valuable for employer plans—especially those with high-deductible health insurance.

MediBid for Individuals

U.S. patients willing to travel and able to pay upfront for care can take advantage of the online service, MediBid. Patients register and request bids or estimates for specific procedures on MediBid’s website for the services of, say, a physician, surgeon, dermatologist, chiropractor, dentist or numerous other medical specialties. MediBid-affiliated physicians and other medical providers respond to patient requests and submit competitive bids for the business of patients seeking care. Patients can choose from medical providers in the United States and even some providers outside the country. MediBid facilitates the transaction but the agreement is between doctor and patient, both of whom must come to an agreement on the price and service.

Business at the site is growing. For example, last year the company facilitated:

- More than 50 knee replacements, with an average of five bids per request and some getting as many as 22. The average price was about $12,000, almost one-third of what insurance companies typically pay and about half of Medicare’s average price.

- Sixty-six colonoscopies with an average of three bids per request and some getting as many as six. The average price was between $500 and $800, half of what you would ordinarily expect to pay.

- Forty-five knee and shoulder arthroscopic surgeries, with average prices between $4,000 and $5,000.

- Thirty-three hernia repairs with an average price of $3,500.

MediBid for Employer Plans

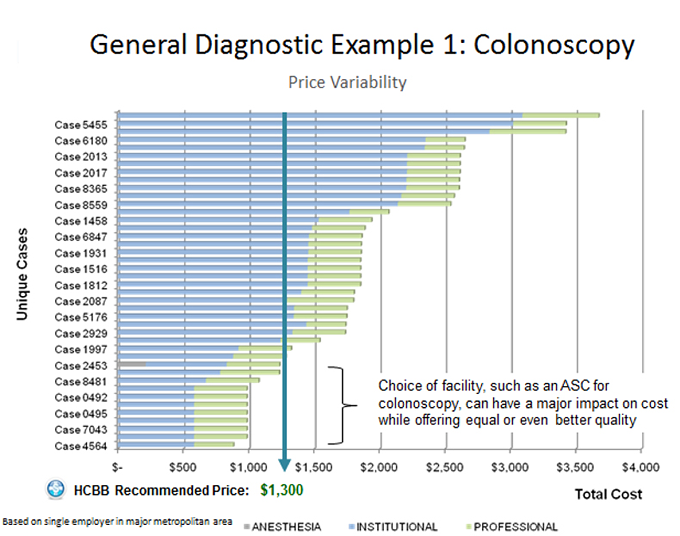

Following the MediBid model, employers cover no more than the median cost—requiring the employee to pay excess charges if they choose a provider who charges above the median. Take a colonoscopy for example. The price in a large city varies considerably—and the upper estimates approach $9,000 if the procedure is done at an out-of-network hospital. Health plans negotiate network discounts that are lower, but these rates still range from $900-$3,600 in the Midwestern city that was the source of the data in the graph below.

In this example, the recommended price is $1,300—which is roughly the average price in the area. If the employee chooses a higher cost provider, the employee pays the extra out of pocket. If the price that is lower, the savings are shared between employee and employer. MediBid reports it often helps patients locate colonoscopies prices at less than half of the recommended price.

Healthcare Blue Book for Individuals

Using Healthcare Blue Book, patients can unveil some of the mystery surrounding what is a reasonable medical price. Healthcare Blue Book tracks a range of prices in each zip code based on claims from its health plan clients. Although individuals cannot see the specific price each hospital and clinic charges for each service, patients can see the average or reasonable price within a given area. For instance, if the Healthcare Blue Book recommended price for a colonoscopy in the area is $1,300, patients know that is a fair price that is widely available. Moreover, patients know that up to one-quarter to one-third of area providers actually charge less.

Healthcare Blue Book for Employer Plans

Healthcare Blue Book is a valuable tool that helps patients identify specific clinics, hospitals and facilities that have the best prices on medical procedures. Healthcare Blue Book displays the median price and a bar graph comparing how costs vary among area hospitals and clinics. In one Midwestern city, a patient seeking a colonoscopy can see that a hospital charges $3,600 compared to an ambulatory surgery center (ASC) that charges less than $1,000. Employees undergoing a colonoscopy at an ASC could realize savings of $2,500 compared to the most expensive facilities.

Allowing Medicare Patients Access to the Marketplace

In proposing a balanced federal budget over the next ten years, House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan proposes to spend the same amount of money on Medicare as will be spent under current law. The difference? Under current law, billions of dollars in reduced Medicare spending will be used to subsidize a new entitlement (ObamaCare). Under Ryan’s approach, ObamaCare will be repealed and the Medicare reductions will be used to stop spiraling federal debt.

There are also other differences. Under the administration’s health reform law, there is only one effective way to hold Medicare to a lower spending path: reduced fees paid to doctors, hospitals and other providers.

Seniors will become less desirable to providers than welfare mothers from a financial point of view. As they are relegated to the rear of the waiting lines, the elderly and the disabled may have to turn to sources of care that many Medicaid patients turn to today: community health centers and the emergency rooms of safety net hospitals.

In contrast to this archaic approach to controlling costs, the Ryan budget will allow us to achieve savings in a better way. By moving Medicare into to 21st century and allowing beneficiaries to do may of the things that younger patients do routinely, we can reduce costs and leave beneficiaries better off at the same time. Many of these same reforms will help save billions of dollars in Medicaid as well.

A central role in the Ryan budget is played by Medicare Advantage plans. About one in four seniors is enrolled in these plans and studies show that the best of them have lower costs and meet higher quality standards than traditional Medicare. These plans are also proving to be laboratories in which many of the ideas favored by the Obama administration are being tested and vetted, including medical homes, integrated care, coordinated care, etc.

It is surprising, therefore, that the Obama administration plans to cut the funds for these plans, causing about one in every two enrollees to lose coverage in the next few years. By contrast, the Ryan budget envisions giving more seniors the opportunity to enroll, giving the plans much more flexibility than they have today and erecting better rules under which the plans compete for enrollees.

For those who remain in traditional Medicare, there is also much that can be done. Here are 10 suggestions:

Telephone and Email. Many conditions do not require a doctor visit. The ability to consult by phone or electronically could save time and money for seniors and make care more accessible. Medicare should make this option available and contribute toward the costs – paying less than it would pay for an office visit. The price paid by the patient, however, should be the market price that other patients are paying, not an arbitrary fee set by the government.

Walk-In Clinics. Studies show that walk-in clinics are providing high-quality, low-cost care for a fraction of what similar care would cost at a doctor’s office or at a hospital emergency room. Medicare should not only pay for these services, it should pay the market price (rather than Medicare’s fee schedule price) in order to encourage their expansion to more of the Medicare population. A similar approach for Medicaid would dramatically increase access to care for low-income families all across the country and lower Medicaid’s costs at the same time.

Nurses. Not every medical service requires the attention of a medical doctor. Yet, Medicare’s current fee schedule discourages the substitution of non-doctor personnel – even though these services are often appropriate and have the potential to greatly lower costs. Medicare (and Medicaid) could actually save money by paying higher fees for services delivered by nurses and other paramedical personnel.

Chronic Care. The current system encourages one-visit-one-illness-treated medicine. This practice raises costs and lowers quality. Instead, physicians’ should be encouraged to treat the whole patient on every visit, including all co-morbidities. Here is another instance where Medicare could actually save money by paying higher fees.

Health Savings Accounts. The RAND Corporation finds that these accounts lower costs by as much as 30 percent with no harm to the most vulnerable patients. For seniors, the accounts should be Roth accounts (after tax deposits and tax free withdrawals for any purpose) and in order to expand access to care, patients should be free to pay market prices rather than Medicare’s fee schedule for medical services.

Rational Insurance Design. Instead of paying Medigap premiums, a senior should be able to deposit, say, $2,000 a year in a Health Savings Account. The senior would be responsible for the first $2,000 of medical expenses, but would have complete catastrophic protection above that amount.

Concierge Care. Seniors should be able to contract with doctors for all of their primary care services rather than paying on a fee for service basis. Concierge doctors spend more time with their patients, offer more convenient and timely care and serve as agents of their patients in negotiating the complexities of the health care system. There is some evidence that this type of medicine lowers the overall cost of care. Because this potentially saves money for taxpayers, Medicare should be willing to pay a portion of the fee.

Medical Tourism. As noted, Canadian patients who come to the United States for procedures that are not readily available in their own country typically pay half as much as Americans pay. Seniors should also have the option to travel for lower cost, higher quality care and they should be able to share in any money they save taxpayers. Also, when seniors choose to retire in Mexico and other places south of our border, Medicare should cover their medical expenses in those countries. The bill will be a lot lower than if they return to the United States for their care.

Experiments. Is Medicare encouraging the kind of services seniors most want? Would they be willing to pay out of pocket for better care or more convenient care? We cannot know unless we experiment to find out. Most doctors would remain under the current system. But a few doctors should be allowed to experiment with patient-pleasing alternatives.

Innovation. Instead of dictating a fee schedule to the provider community and trying to enforce arbitrary quality standards, Medicare should let the supply side of the market take the lead. Every doctor and every hospital should be free (and even encouraged) to propose alternative ways of being paid. Medicare should be willing to accept any new arrangement that (1) lowers costs to the taxpayers and (2) raises the quality of care patients receive.

Finally, there is nothing in the Ryan budget that would prevent us from rational health reform for the under-65 population. We could replace the existing system of tax subsidies with refundable tax credits that would produce a form of universal coverage without the Rube Goldberg intricacies of ObamaCare and all its perverse incentives.